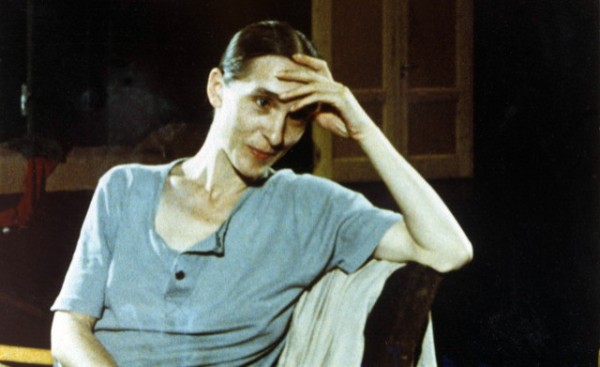

Rarely screened 1983 documentary delves into Pina Bausch’s creative process (photo courtesy Icarus Films)

“ONE DAY PINA ASKED…” (UN JOUR PINA A DEMANDÉ) (Chantal Akerman, 1983)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

30 Lafayette Ave. between Ashland Pl. & St. Felix St.

Thursday, April 28, 7:00 & 9:30

Series continues through May 1

718-636-4100

www.bam.org

In 1982, Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman followed Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal on a five-week tour of Europe as the cutting-edge troupe traveled to Milan, Venice, and Avignon. “I was deeply touched by her lengthy performances that mingle in your head,” Akerman says at the beginning of the resulting documentary, “One Day Pina Asked . . . ,” continuing, “I have the feeling that the images we brought back do not convey this very much and often betray it.” Akerman (Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles; Je tu il elle) needn’t have worried; her fifty-seven-minute film, made for the Repères sur la Modern Dance French television series, is filled with memorable moments that more than do justice to Bausch’s unique form of dance theater. From 1973 up to her death in 2009 at the age of sixty-eight, Bausch created compelling works that examined the male-female dynamic and the concepts of love and connection with revolutionary stagings that included spoken word, unusual costuming, an unpredictable movement vocabulary, and performers of all shapes, sizes, and ages. Akerman captures the troupe, consisting of twenty-six dancers from thirteen countries, in run-throughs, rehearsals, and live presentations of Komm Tanz Mit Mir (Come Dance with Me), Nelken (Carnations), 1980, Kontakthof, and Walzer, often focusing on individual dancers in extreme close-ups that reveal their relationship with their performance. Although Bausch, forty at the time, is seen only at the beginning and end of the documentary, her creative process is always at center stage. At one point, dancer Lutz Förster tells a story of performing George and Ira Gershwins’ “The Man I Love” in sign language in response to Bausch’s asking the troupe to name something they’re proud of. Förster, who took over as artistic director in April 2013, first performs the song for Akerman, then later is shown performing it in Nelken. (Bausch fans will also recognize such longtime company members as Héléna Pikon, Nazareth Panadero, and Dominique Mercy.)

In 1982, Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman followed Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal on a five-week tour of Europe as the cutting-edge troupe traveled to Milan, Venice, and Avignon. “I was deeply touched by her lengthy performances that mingle in your head,” Akerman says at the beginning of the resulting documentary, “One Day Pina Asked . . . ,” continuing, “I have the feeling that the images we brought back do not convey this very much and often betray it.” Akerman (Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles; Je tu il elle) needn’t have worried; her fifty-seven-minute film, made for the Repères sur la Modern Dance French television series, is filled with memorable moments that more than do justice to Bausch’s unique form of dance theater. From 1973 up to her death in 2009 at the age of sixty-eight, Bausch created compelling works that examined the male-female dynamic and the concepts of love and connection with revolutionary stagings that included spoken word, unusual costuming, an unpredictable movement vocabulary, and performers of all shapes, sizes, and ages. Akerman captures the troupe, consisting of twenty-six dancers from thirteen countries, in run-throughs, rehearsals, and live presentations of Komm Tanz Mit Mir (Come Dance with Me), Nelken (Carnations), 1980, Kontakthof, and Walzer, often focusing on individual dancers in extreme close-ups that reveal their relationship with their performance. Although Bausch, forty at the time, is seen only at the beginning and end of the documentary, her creative process is always at center stage. At one point, dancer Lutz Förster tells a story of performing George and Ira Gershwins’ “The Man I Love” in sign language in response to Bausch’s asking the troupe to name something they’re proud of. Förster, who took over as artistic director in April 2013, first performs the song for Akerman, then later is shown performing it in Nelken. (Bausch fans will also recognize such longtime company members as Héléna Pikon, Nazareth Panadero, and Dominique Mercy.)

Documentary includes inside look at such Tanztheater Wuppertal productions as NELKEN (photo courtesy Icarus Films)

As was her style, Akerman often leaves her camera static, letting the action occur on its own, which is particularly beautiful when she films a dance through a faraway door as shadowy figures circle around the other side. It’s all surprisingly intimate, not showy, rewarding viewers with the feeling that they are just next to the dancers, backstage or in the wings, unnoticed, as the process unfolds, the camera serving as their surrogate. And it works whether you’re a longtime fan of Bausch, only discovered her by seeing Wim Wenders’s Oscar-nominated 3D film Pina, or never heard of her. “This film is more than a documentary on Pina Bausch’s work,” a narrator says introducing the film. “It is a journey through her world, through her unwavering quest for love.” ”One Day Pina Asked…” is screening April 28 at 7:00 and 9:30 at BAM Rose Cinemas as part of the month-long BAMcinématek series “Chantal Akerman: Images between the Images,” which pays tribute to the influential, experimental director, who died in October 2015, reportedly by suicide; the earlier showing will be preceded by two Akerman shorts featuring cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton, 2002’s Avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton and 1989’s Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher. Not coincidentally, Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal has been performing at BAM since 1984. The film series continues through May 1 with such other films by Akerman as La Captive, Jeanne Dielman, and From the East.

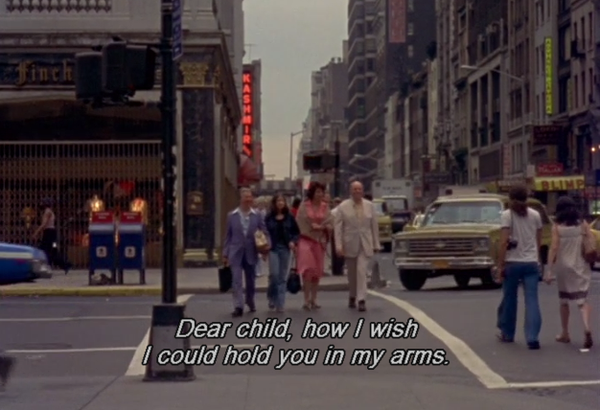

In 1971, twenty-year-old Chantal Akerman moved to New York City from her native Belgium, determined to become a filmmaker. Teaming up with cinematographer Babette Mangolte, she made several experimental films, including

In 1971, twenty-year-old Chantal Akerman moved to New York City from her native Belgium, determined to become a filmmaker. Teaming up with cinematographer Babette Mangolte, she made several experimental films, including

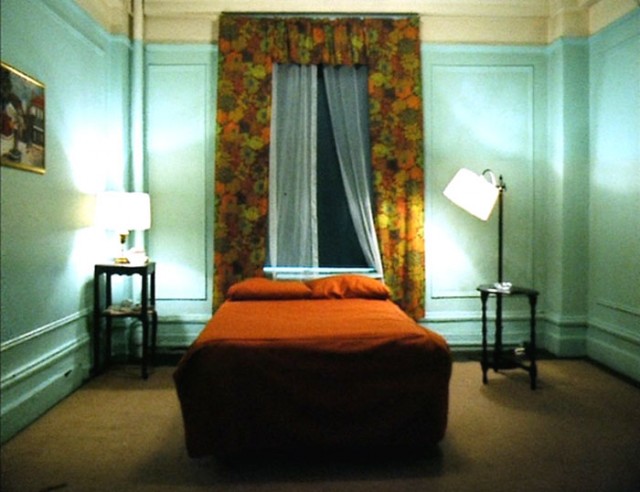

Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie was meant to be a kind of public eulogy for her beloved mother, Natalia (Nelly) Akerman, who died in 2014 at the age of eighty-six, shortly after Chantal had completed shooting forty hours of material with her. But it also ended up becoming, in its own way, a public eulogy for the highly influential Belgian auteur herself, as she died on October 5, 2015, at the age of sixty-five, only a few months after the film screened to widespread acclaim at several festivals (except at Locarno, where it was actually booed). Her death was reportedly a suicide, following a deep depression brought on by the loss of her mother. No Home Movie primarily consists of static shots inside Nelly’s Brussels apartment as she goes about her usual business, reading, eating, preparing to go for a walk, and taking naps. Akerman sets down either a handheld camera or a smartphone and lets her mother walk in and out of the frame; Akerman very rarely moves the camera or follows her mother around, instead keeping it near doorways and windows. She’s simply capturing the natural rhythms and pace of an old woman’s life. Occasionally the two sit down together in the kitchen and eat while discussing family history and gossip, Judaism, WWII, and the Nazis. (The elder Akerman was a Holocaust survivor who spent time in Auschwitz.) They also Skype each other as Chantal travels to film festivals and other places. “I want to show there is no distance in the world,” she tells her mother, who Skypes back, “You always have such ideas! Don’t you, sweetheart.” In another exchange, the daughter says, “You think I’m good for nothing!” to which the mother replies, “Not at all! You know all sorts of things others don’t know.”

Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie was meant to be a kind of public eulogy for her beloved mother, Natalia (Nelly) Akerman, who died in 2014 at the age of eighty-six, shortly after Chantal had completed shooting forty hours of material with her. But it also ended up becoming, in its own way, a public eulogy for the highly influential Belgian auteur herself, as she died on October 5, 2015, at the age of sixty-five, only a few months after the film screened to widespread acclaim at several festivals (except at Locarno, where it was actually booed). Her death was reportedly a suicide, following a deep depression brought on by the loss of her mother. No Home Movie primarily consists of static shots inside Nelly’s Brussels apartment as she goes about her usual business, reading, eating, preparing to go for a walk, and taking naps. Akerman sets down either a handheld camera or a smartphone and lets her mother walk in and out of the frame; Akerman very rarely moves the camera or follows her mother around, instead keeping it near doorways and windows. She’s simply capturing the natural rhythms and pace of an old woman’s life. Occasionally the two sit down together in the kitchen and eat while discussing family history and gossip, Judaism, WWII, and the Nazis. (The elder Akerman was a Holocaust survivor who spent time in Auschwitz.) They also Skype each other as Chantal travels to film festivals and other places. “I want to show there is no distance in the world,” she tells her mother, who Skypes back, “You always have such ideas! Don’t you, sweetheart.” In another exchange, the daughter says, “You think I’m good for nothing!” to which the mother replies, “Not at all! You know all sorts of things others don’t know.”