TRAGEDIES OF YOUTH — NOBUHIKO OBAYASHI’S WAR TRILOGY: SEVEN WEEKS (NO NO NANANANOKA) (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 2014)

Japan Society virtual cinema

Available on demand through August 6, seven-day rental $10 per film, $24 for all three

japansociety.org

In December 2015, Japan Society presented the two-weekend, ten-film series “Nobuhiko Obayashi: A Retrospective,” which revealed that the Japanese auteur was so much more than just the director of the 1977 cult classic House. In commemoration of the recent death of the iconoclastic, eclectic writer-director, who passed away in April 2020 from lung cancer at the age of eighty-two, Japan Society is hosting a special monthlong online screening of his War Trilogy, consisting of 2012’s Casting Blossoms to the Sky, set in the aftermath of the devastating 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, 2017’s Hanagatami, an adaptation of Kazuo Dan’s 1937 novella about a group of students falling in and out of love in prewar Japan, and the 2014 epic family drama Seven Weeks.

A tribute to Obayashi’s late friend and colleague Hyoji Suzuki, who started an independent film workshop in Ashibetsu in 1993 and died of pancreatic cancer four years later at the age of thirty-six, Seven Weeks was shot in and around that Hokkaido village over the course of five weeks. Ninety-two-year-old patriarch Mitsuo Suzuki (Toru Shinagawa), a local retired doctor who now runs the Starry Cultural Center gift shop (a nod to Suzuki’s Hoshi no Furusato Ashibetsu Eiga Gakko, or Starry Beautiful Home Ashibetsu Film School), is on his deathbed, and various relatives are arriving to say goodbye and participate in the nanana no ka Buddhist ritual, in which they will hold memorials once a week for seven weeks following his death. The mourners include Mitsuo’s sister, Eiko (Tokie Hidari), grandchildren Fuyuki (Takehiro Murata), Haruhiko (Yutaka Matsuhige), Akito (Shunsuke Kubozuka), and Kanna (Saki Terashima), and great-granddaughter Kasane (Hirona Yamazaki), in addition to his nurse, Nobuko Shimizu (Takako Tokiwa). During the seven weeks, family members relive the past, uncovering surprising secrets about the young Mitsuo (Shusaku Uchida), his harmonica-playing friend Ono (Takao Ito), and the woman they both admire, Ayano (Yumi Adachi), as Obayashi weaves together past and present through flashbacks, the appearance of dead characters, and painting and poetry (several of the characters share a love of the poems of Nakahara Chuya).

But the film, shot in lush, fairy-tale-like colors by cinematographer Hisaki Mikimoto and featuring a sweeping score by Kôsuke Yamashita and a kind of Greek chorus embodied by the unusual Japanese band the Pascals, is not merely about the travails of one extended family; it is also very much about the rebuilding of Japanese society in the wake of WWII, the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011, and the ensuing Fukushima nuclear disaster. In fact, all of the clocks and watches in Seven Weeks are perpetually stopped at 2:45 pm, the exact time the horrific 3/11 events began. Obayashi also investigates the Soviet invasion of Sakhalin Island in August 1945 and the abuse of Korean migrant workers in Japanese mines as he explores the complex issue of the meaning of home. Seven Weeks is a beautifully told tale of memory and loss, of art and war, a summing up not only of Obayashi’s career but of twentieth-century Japan, with plenty of the director’s unique trademark style. “How do I paint the world?” Mitsuo asks at one point, something Obayashi has achieved in this deeply involving and wonderfully mysterious film. Fortunately for all of us, Obayashi was not quite done painting the world, continuing a legacy that is at last being celebrated here in the West.

TRAGEDIES OF YOUTH — NOBUHIKO OBAYASHI’S WAR TRILOGY: CASTING BLOSSOMS TO THE SKY (KONO SORA NO HANA: NAGAOKA HANABI MONOGATARI) (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 2014)

japansociety.org

“If people made pretty fireworks instead of bombs, there wouldn’t have been any wars,” says journalist Reiko Endō (Yasuko Matsuyuki), quoting wandering artist Kiyoshi Yamashita at the start of Nobuhiko Ōbayashi’s Casting Blossoms to the Sky. The first of the eclectic Japanese auteur’s War Trilogy, the film, based on actual experiences, is essentially an audiovisual essay, “Reiko Endō’s Wonderland: A Journey of Emotions to Nagaoka,” detailing Endō’s trip to Nagaoka in Niigata Prefecture, as the local citizenry share true tales of WWII and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. (Nagaoka took in more than a thousand evacuees from Fukushima.) Ōbayashi goes back and forth between the past and the present, from the summer in 1945 when Nagaoka was bombed by the United States to the latest edition of the city’s annual fireworks display, which honor the victims of Pearl Harbor, the bombings of Nagaoka, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, and the 2011 disaster.

With the day of the fireworks show approaching, Endō rides with wise cabdriver Akiyoshi Muraoka (Takashi Sasano), as she, and we, discover the city’s history of war and remembrance. Endō meets with her ex-boyfriend, Kenichi Katayama (Masahiro Takashima), who is in charge of the school play at Chuetsu High and chooses There’s Still Time Until a War by a mysterious girl named Jana Motoki (Minami Inomata) who rides a unicycle through the halls and down the streets of the neighborhood. Endō learns from the inhabitants themselves, including military history researcher Takashi Mishima (Akiyoshi Muraoka) and triathlete and potato farmer Goro Matsushita (Toshio Kakei), who built a memorial using a fragment from one of the incendiary bombs dropped on Nagaoka; war veteran and local fireworks legend Seijiro Nose (Akira Emoto); reporter Wakako Inoue (Natsuka Harada), who walks Endō through important parts of the city; Yoshie Yamafuji, who lost much of her family in the bombings; artist Yasunari Honmura, who uses his paintings as reminders of the horrors of war; and numerous other survivors and relatives of the dead.

Journalist Reiko Endō (Yasuko Matsuyuki) goes on quite a ride with cabdriver Akiyoshi Muraoka (Takashi Sasano) in Nobuhiko Ōbayashi’s Casting Blossoms to the Sky

Casting Blossoms to the Sky is made in Obayashi’s unique style, with visually stunning backdrops (real and green-screened), bright, brash color schemes, professional and nonprofessional actors, and computer-generated imagery that can feel rather goofy. The film was imaginatively shot by Yûdai Katô and Hisaki Sanbongi, with lovely, often garishly beautiful production design by Kôichi Takeuchi and playful editing by Obayashi and Hisaki Sanbongi, using cute cinematic techniques. The characters sometimes turn and speak directly into the camera, further establishing the film as a cautionary tale.

“I don’t know anything about war and it’s never crossed my mind,” a young student named Ryo says to Katayama, who replies, “It’s the citizens’ duty to tell the story. There are adults who think war is necessary but not the children. That’s why it’s up to the children to make peace.”

In one of the most moving scenes, a black-and-white flashback to 2009 during a fierce storm, Endō’s mother (Shiho Fujimura) says to her, “Life is connected,” a statement that is at the heart of Obayashi’s message. But no matter how didactic some of the dialogue is and how silly the visuals can get, accompanied by Joe Hisaishi’s emotional score, Casting Blossoms to the Sky has an innate charm that is so endearing you will forgive its flaws. At one point Katayama explains, “The fireworks are a prayer.” So is Casting Blossoms to the Sky, which, like fireworks, is quite a sight to behold.

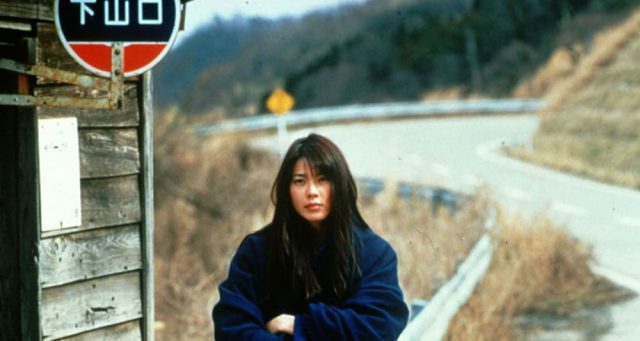

To celebrate the theatrical release of Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest work, Shoplifters, the Palme d’Or winner that opens November 23, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting six of the master’s earlier tales, concentrating on his exquisite depiction of family life. Running November 19-22, the mini-festival provides a terrific entry into the oeuvre of Kore-eda, a visionary who tells a story like no one else. “Six by Kore-eda” begins with his first fiction film, Maborosi, which followed three documentaries (Lessons from a Calf, However . . . , August without Him). After Yumiko’s husband, Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano), mysteriously commits suicide, she (Makiko Esumi) gets remarried and moves to her new husband’s (Takashi Naitō) small seaside village home with her son (Gohki Kashima), where she begins to put her life back together. This stunning film is marvelously slow-paced, lingering on characters in the distance, down narrow alleys, across gorgeous horizons, with very little camera movement by cinematographer Masao Nakabori. Maborosi, the only one of his films he didn’t write — the screenplay is by Yoshihisa Ogita, based on the novel by Teru Miyamoto — is a stunning debut from one of the leading members of Japan’s fifth generation. It is screening at the Walter Reade Theater on November 19 at 6:30 and November 22 at 9:00

To celebrate the theatrical release of Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest work, Shoplifters, the Palme d’Or winner that opens November 23, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting six of the master’s earlier tales, concentrating on his exquisite depiction of family life. Running November 19-22, the mini-festival provides a terrific entry into the oeuvre of Kore-eda, a visionary who tells a story like no one else. “Six by Kore-eda” begins with his first fiction film, Maborosi, which followed three documentaries (Lessons from a Calf, However . . . , August without Him). After Yumiko’s husband, Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano), mysteriously commits suicide, she (Makiko Esumi) gets remarried and moves to her new husband’s (Takashi Naitō) small seaside village home with her son (Gohki Kashima), where she begins to put her life back together. This stunning film is marvelously slow-paced, lingering on characters in the distance, down narrow alleys, across gorgeous horizons, with very little camera movement by cinematographer Masao Nakabori. Maborosi, the only one of his films he didn’t write — the screenplay is by Yoshihisa Ogita, based on the novel by Teru Miyamoto — is a stunning debut from one of the leading members of Japan’s fifth generation. It is screening at the Walter Reade Theater on November 19 at 6:30 and November 22 at 9:00

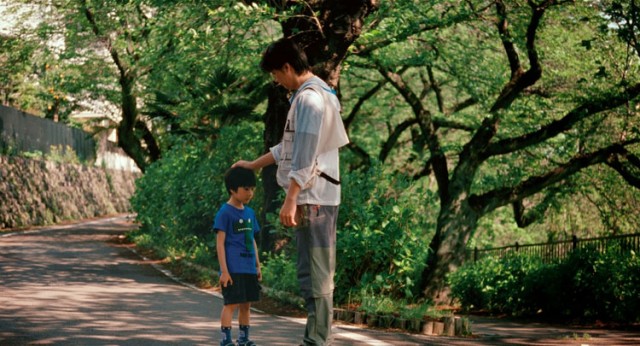

Kore-eda’s second narrative feature, After Life, is an eminently thoughtful film about two of his recurring themes: death and memory. Every Monday, the deceased arrive at a way station where they have three days to decide on a single memory they can bring with them into heaven. Once chosen, the memory is re-created on film, and the person goes on to the next step of his or her journey, to be replaced by a new batch of souls. The way station is staffed by guides, including Takashi Mochizuki (Arata), Shiori Satonaka (Erika Oda), and Satoru Kawashima (Susumu Terajima), whose job it is to interview the new arrivals and help them select a memory and then bring it to life on-screen. Some want to take with them an idyllic moment from childhood, others a remembrance of a lost love, but a few are either unable to or refuse to come up with one, which challenges the staff. Twenty-one-year-old Yūsuke Iseya declares, “I have no intention of choosing. None,” while seventy-year-old Ichiro Watanabe (Taketoshi Naito) is having difficulty deciding on the exact moment, reevaluating and reflecting on the life he led. As the week continues, the guides look back on their lives as well, sharing intimate details, one of which leads to an emotional finale.

Kore-eda’s second narrative feature, After Life, is an eminently thoughtful film about two of his recurring themes: death and memory. Every Monday, the deceased arrive at a way station where they have three days to decide on a single memory they can bring with them into heaven. Once chosen, the memory is re-created on film, and the person goes on to the next step of his or her journey, to be replaced by a new batch of souls. The way station is staffed by guides, including Takashi Mochizuki (Arata), Shiori Satonaka (Erika Oda), and Satoru Kawashima (Susumu Terajima), whose job it is to interview the new arrivals and help them select a memory and then bring it to life on-screen. Some want to take with them an idyllic moment from childhood, others a remembrance of a lost love, but a few are either unable to or refuse to come up with one, which challenges the staff. Twenty-one-year-old Yūsuke Iseya declares, “I have no intention of choosing. None,” while seventy-year-old Ichiro Watanabe (Taketoshi Naito) is having difficulty deciding on the exact moment, reevaluating and reflecting on the life he led. As the week continues, the guides look back on their lives as well, sharing intimate details, one of which leads to an emotional finale.

We called Tetsuya Nakashima’s 2004 hit, Kamikaze Girls, the “otaku version of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amelie,” referring to it as “fresh,” “frenetic,” “fast-paced,” and “very funny.” His feature-length follow-up, the stunningly gorgeous Memories of Matsuko, also recalls Amelie and all those other adjectives, albeit with much more sadness. Miki Nakatani (Ring, Silk) stars as Matsuko, a sweet woman who spent her life just looking to be loved but instead found nothing but heartbreak, deception, and physical and emotional abuse. But Memories of Matsuko, is not a depressing melodrama, even if Nakashima (Confessions, The World of Kanako) incorporates touches of Douglas Sirk every now and again. The film is drenched in glorious Technicolor, often breaking out into bright and cheerful musical numbers straight out of a 1950s fantasy world. As the movie begins, Matsuko has been found murdered, and her long-estranged brother (Akira Emoto) has sent his son, Sho (Eita), who never knew she existed, to clean out her apartment. As Sho goes through the mess she left behind, the film flashes back to critical moments in Matsuko’s life — and he also meets some crazy characters in the present. It’s difficult rooting for the endearing Matsuko knowing what becomes of her, but Nakashima’s remarkable visual style will grab you and never let go. And like Audrey Tatou in Amelie, Nakatani — who won a host of Japanese acting awards for her outstanding performance — is just a marvel to watch. Memories of Matsuko is a fine choice to conclude Japan Society’s rather eclectic 2016 Globus Film Series “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film.” As curator Michael Raine notes, “The ubiquity of music and song in postwar Japanese cinema became an anti-naturalist resource for modernist filmmakers to characterize social groups (Twilight Saloon,

We called Tetsuya Nakashima’s 2004 hit, Kamikaze Girls, the “otaku version of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amelie,” referring to it as “fresh,” “frenetic,” “fast-paced,” and “very funny.” His feature-length follow-up, the stunningly gorgeous Memories of Matsuko, also recalls Amelie and all those other adjectives, albeit with much more sadness. Miki Nakatani (Ring, Silk) stars as Matsuko, a sweet woman who spent her life just looking to be loved but instead found nothing but heartbreak, deception, and physical and emotional abuse. But Memories of Matsuko, is not a depressing melodrama, even if Nakashima (Confessions, The World of Kanako) incorporates touches of Douglas Sirk every now and again. The film is drenched in glorious Technicolor, often breaking out into bright and cheerful musical numbers straight out of a 1950s fantasy world. As the movie begins, Matsuko has been found murdered, and her long-estranged brother (Akira Emoto) has sent his son, Sho (Eita), who never knew she existed, to clean out her apartment. As Sho goes through the mess she left behind, the film flashes back to critical moments in Matsuko’s life — and he also meets some crazy characters in the present. It’s difficult rooting for the endearing Matsuko knowing what becomes of her, but Nakashima’s remarkable visual style will grab you and never let go. And like Audrey Tatou in Amelie, Nakatani — who won a host of Japanese acting awards for her outstanding performance — is just a marvel to watch. Memories of Matsuko is a fine choice to conclude Japan Society’s rather eclectic 2016 Globus Film Series “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film.” As curator Michael Raine notes, “The ubiquity of music and song in postwar Japanese cinema became an anti-naturalist resource for modernist filmmakers to characterize social groups (Twilight Saloon,

For more than half a century, Hollywood has remade a plethora of Asian films, from The Magnificent Seven (Seven Samurai) to The Departed (Infernal Affairs), from Shall We Dance? (Sharu wi Dansu?) to The Grudge (Ju-On), among so many others. But there’s a relatively new trend in which Japan, Korea, and China are now remaking American films, including Ghost: Mouichido Dakishimetai (Ghost), Wo Zhi Nv Ren Xin (What Women Want), and Saidoweizu (Sideways). One of the latest, and best, is Japanese-born Korean director Lee Sang-il’s spectacularly honest and faithful remake of Clint Eastwood’s 1992 Oscar-winning revisionist Western, Unforgiven — in some ways returning the favor of Eastwood’s having starred in Sergio Leone’s 1964 spaghetti Western A Fistful of Dollars, a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. In Unforgiven, Ken Watanabe, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in The Last Samurai and starred in Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima, plays Jubei Kamata, the Japanese version of Eastwood’s William Munny.

For more than half a century, Hollywood has remade a plethora of Asian films, from The Magnificent Seven (Seven Samurai) to The Departed (Infernal Affairs), from Shall We Dance? (Sharu wi Dansu?) to The Grudge (Ju-On), among so many others. But there’s a relatively new trend in which Japan, Korea, and China are now remaking American films, including Ghost: Mouichido Dakishimetai (Ghost), Wo Zhi Nv Ren Xin (What Women Want), and Saidoweizu (Sideways). One of the latest, and best, is Japanese-born Korean director Lee Sang-il’s spectacularly honest and faithful remake of Clint Eastwood’s 1992 Oscar-winning revisionist Western, Unforgiven — in some ways returning the favor of Eastwood’s having starred in Sergio Leone’s 1964 spaghetti Western A Fistful of Dollars, a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. In Unforgiven, Ken Watanabe, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in The Last Samurai and starred in Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima, plays Jubei Kamata, the Japanese version of Eastwood’s William Munny.