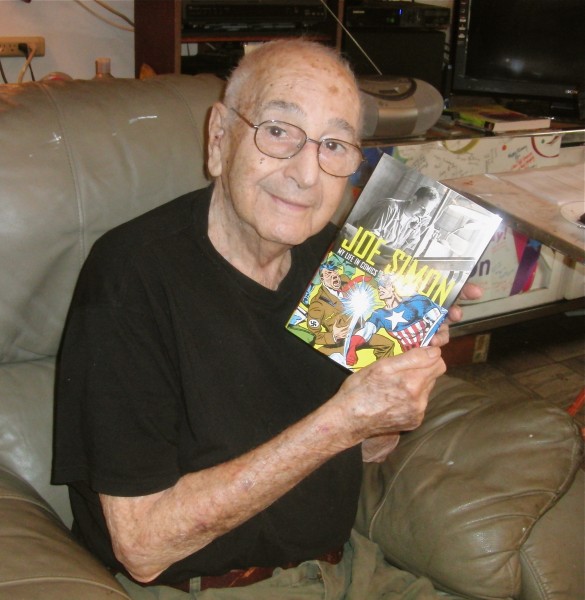

JOE SIMON: MY LIFE IN COMICS (Titan, June 2011, $24.95)

www.titanbooks.com

The potential summer blockbuster Captain America opens in theaters today, but that would not have been possible without Joe Simon. Back in 1941, Simon, a native New Yorker born and raised in Rochester, teamed up with Jacob Kurtzberg, better known as Jack Kirby, and created the red, white, and blue superhero. The villain for the cover of the first issue? They came up with just the right one. “Adolf Hitler would be the perfect foil for our next new character, what with his hair and that stupid-looking moustache and his goose-stepping. He was like a cartoon anyway,” Simon writes in his entertaining, intimate, and refreshingly honest memoir, My Life in Comics (Titan, June 2011, $24.95). “We knew what was happening in Europe, and we were outraged by the Nazis — totally outraged. We thought it was a good time for a patriotic hero. . . . And that’s how Captain America was created.”

Today the ninety-seven-year-old Simon spends most of his time in his cluttered apartment just west of the Theater District, surrounded by classic drawings, sketches, and comic book covers. His works line the walls, a veritable history of the industry in black and white and color. One of the many highlights is a grand depiction of the Last Supper populated with his characters, a painting he completed with his daughter Gail. Sitting in his large, comfortable recliner in the middle of the living room, Simon is thrilled to tell tales of his days serving in the Coast Guard with Jack Dempsey, meeting Damon Runyon and Max Baer while a journalist, riding horses in Forest Park, and mentoring such comic book legends as Stan Lee. As we talk, he pulls out stunning works accumulated from throughout his fascinating career. He pauses to congratulate one of his granddaughters for passing an important college test; seven of his eight grandkids were scheduled to fly to Hollywood to walk the red carpet at the star-studded Captain America premiere. Among the other characters Simon had a hand in either creating or developing were the Fiery Mask, the Fly, the Blue Bolt, Sandman, the Newsboy Legion, Manhunter, and the Boy Commandos. An engaging character himself with a sharp memory and a wicked sense of humor, Simon discussed his book and life with twi-ny shortly before the release of the Captain America movie.

twi-ny: What was the experience like going through your past to put together My Life in Comics? Were there any particular parts of your life that were more difficult to talk about than others?

Joe Simon: This was the first time I revealed some of the more intimate details of my life, talking about my wife Harriet and my family, and some of the challenges we’ve faced. It wasn’t really difficult, but it was something I’d never really talked about before.

I feel very lucky because I have my memory. There are things that happened to me ninety years ago — such as the time I met a Civil War veteran — which I remember clearly. I’ve had a lot of exciting things happen to me over the course of ninety-seven years, and it was wonderful to be able to get them down on paper, for everyone to experience.

twi-ny: In the book, you note that you and many of your earliest colleagues come from immigrant Jewish families working in the clothing business in New York City. Do you think that might have had some impact on your eventual career path, creating superheroes and villains dressed in fairy-tale costumes?

JS: That’s a good question. Since tailoring involves creativity, I suppose my parents influenced me in that way, and I’d never really realized it. They also influenced me with their attempts at true romance writing, as badly as they turned out, and with the sense that you stick to it, no matter what you’re trying to accomplish. So in both of those ways they helped me throughout my career. (And of course, thanks to my father, when I came to New York City, I was the best-dressed guy in the comic book business.)

twi-ny: The Captain America movie comes out on July 22. What was your involvement with the picture? What are your thoughts about the film, and about superhero movies in general as they continually get transferred from comic books to the big screen?

JS: Stephen Broussard at Marvel Studios has been keeping me up-to-date, and he arranged for them to film an interview with me. I’ve been liking everything I’ve seen, and am very excited to see how it turns out.

I haven’t seen all of the superhero movies, especially in recent years, but I understand that the Marvel films have been very good. I’ve always thought that Captain America would make a terrific movie and could never understand why all of the earlier attempts sucked so badly. This time, though, they’re sticking to the story that Jack Kirby and I created, so I think they’ll get it right. That’s always the best way to do it — stick with what works.

[Joe Simon: My Life in Comics is available through Amazon and in bookstores everywhere.]