TOM SANTOPIETRO AT B&N

Barnes & Noble

2289 Broadway at Eighty-Second St.

Monday, March 31, free, 6:30

212-362-8835

barnesandnoble.com

tomsantopietro.com

“When Audrey Hepburn died at 8 P.M. on January 20, 1993, at the age of sixty-three, she left behind one Academy Award, two Tony Awards, dozens of lifetime achievement awards, her beloved sons Sean and Luca, companion Robert Wolders, millions of fans, universal acclaim as an indefatigable activist on behalf of the world’s children, and one final surprise — a nearly empty closet.

“She had walked away from the church of fame that rules Hollywood and ever-increasing swaths of the general public yet held onto that fame without even trying. Her elusiveness only increased public interest in her films and clothes as well as her life and loves, but Audrey Hepburn had grown uninterested in rehashing old tales of Hollywood glamour and legendary friends. In an industry which based its self-image on endless awards shows, she was, it was safe to say, the only screen idol about whom a son could convincingly state: ‘Being away from home to win an award was really a lost opportunity. Walking the dogs with her sons was a personal victory.’”

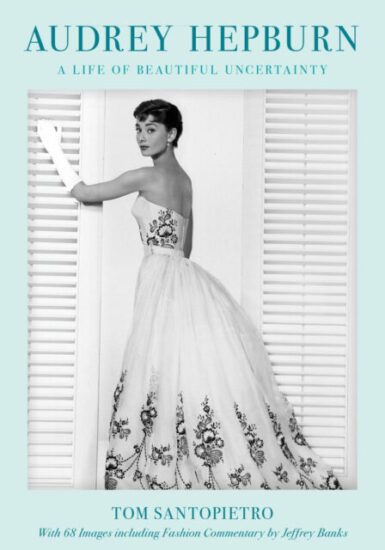

So begins Tom Santopietro’s latest book, Audrey Hepburn: A Life of Beautiful Uncertainty (Rowman & Littlefield, March 2025, $45). Born and raised in Waterbury, Connecticut, Santopietro attended Trinity College in Hartford, then went to the University of Connecticut Law School, also in Hartford.

“I always joke that law school was the three misbegotten years of my life,” Santopietro tells me in a phone interview. “I stayed, I graduated, and as soon as I graduated, I said, I’m never doing this ever. And I never have. You know why? Because I was uninterested. And when it comes to work, we’re all good at what we’re interested in.”

A few weeks before, I had met Santopietro at the Coffee House Club for an Oscars straw vote event he hosted with his friend Simon Jones, who has appeared in such series as Brideshead Revisited, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and The Gilded Age (as Bannister) and in New York in such shows as The Real Thing, Privates on Parade, and, most recently, Trouble in Mind.

Santopietro is a lovely storyteller, in person and in print. Among his previous books are The Sound of Music Story: How a Beguiling Young Novice, a Handsome Austrian Captain, and Ten Singing von Trapp Children Inspired the Most Beloved Film of All Time; Considering Doris Day; The Way We Were: The Making of a Romantic Classic; The Importance of Being Barbra: The Brilliant, Tumultuous Career of Barbra Streisand; Why To Kill a Mockingbird Matters: What Harper Lee’s Book and the Iconic American Film Mean to Us Today; Sinatra in Hollywood; and The Godfather Effect: Changing Hollywood, America, and Me.

In A Life of Beautiful Uncertainty, Santopietro details Hepburn’s fascinating life and career in five acts comprising sixty-two chapters, including “What Price Hollywood,” “The Last Golden Age Star,” “A Star Is (Not Quite Yet) Born,” “Paris When It Fizzles — 1962–1964,” and “Everything Old Is New Again.” He explores Hepburn’s diverse filmography, from the many hits (Roman Holiday, Love in the Afternoon, The Nun’s Story, Charade, My Fair Lady, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Funny Face) to a trio of what he calls “mistakes” (Green Mansions, The Unforgiven, Bloodline).

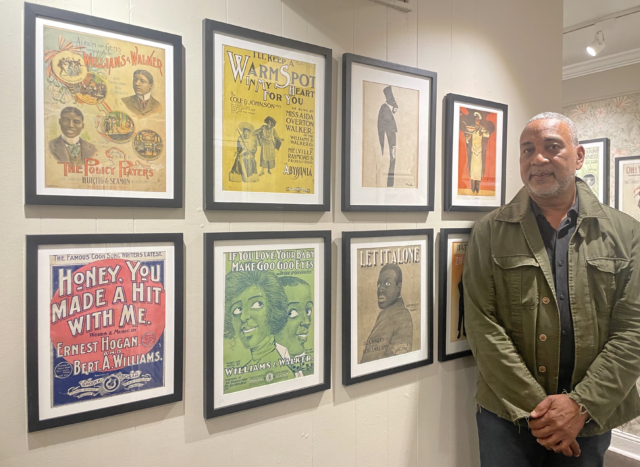

On March 13 at 6:30, Santopietro, who lives on the Upper West Side, will be at the Barnes & Noble on Broadway and Eighty-Second St. to discuss and sign copies of A Life of Beautiful Uncertainty. Below he talks about speaking with Doris Day and Alan Arkin, the decline of theater etiquette, celebrities’ charitable work, and his favorite Audrey Hepburn film.

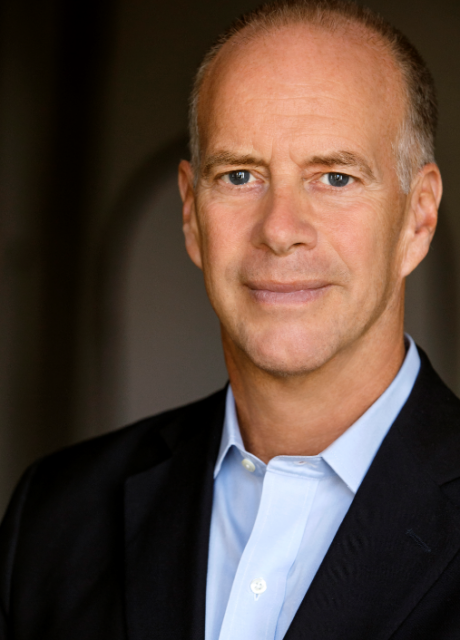

Tom Santopietro will be at Upper West B&N March 31 for NYC launch of his latest book (photo by Joan Marcus)

twi-ny: Where did your love of movies come from?

tom santopietro: When I was a little kid, I always liked movies. But what really accelerated it was when I was at Trinity, I took film courses at Wesleyan, which is in Middletown, and their film department was headed by an incredible woman named Jeanine Basinger. Have you ever met Jeanine?

twi-ny: I haven’t, but I know of her.

ts: She was on the board of the AFI. She was an extraordinary teacher who ignited my love of old films and Hollywood. And that’s where it really took off. Jeanine showed me possibility, and that’s what’s so great. That’s what great teachers do. So anyway, that’s where it really took off. And then I came to New York and worked on several Broadway shows, which I still do, but about twenty years ago, I thought, I want to do something more creative. And that’s how I started to write.

twi-ny: That was your first book, The Importance of Being Barbra, which was published in 2006.

ts: I’ve been fortunate and lucky, and I always joke, I didn’t tell anybody I was writing a book because I thought, What if I don’t finish it? And what if it’s really bad? And then when it was done, I sent it to my oldest friend, and a couple of days later, he called me back. And in a voice of total surprise, he said, It’s good. So I still laugh about that. And that led to Doris Day, Frank Sinatra, and then the Godfather movies.

twi-ny: I’m looking at the books you have written and their subjects. This is something we talked about at the Coffee House, that they’re all beloved icons, beloved films, beloved characters; there’s a lot of love in the room. And one of the things you told me was that that’s one thing you do when choosing a subject.

ts: Yeah, I really do. Because I think, well, you know this, you are a writer. I always say I don’t want to write a book about Stalin because I don’t want that monster in my head for three years. So these are people whose talent I admire so much. And also what I realized, Mark, and this just came to me when the Audrey book was completed, I thought, Oh, I’ve completed a trilogy of books about enormous stars, all of whom are incredibly nice, which is so rare in Hollywood. And that’s Doris Day, Audrey Hepburn, and Julie Andrews, these women who are beloved by their costars. And in the same way, I also realized after it was completed, Oh, I wrote a trilogy of books about family, and those were The Godfather, The Sound of Music, and To Kill a Mockingbird.

So I didn’t even realize it until the trilogy had been completed, but whatever was inside of me clearly needed to be expressed.

twi-ny: In the case of Doris Day, you had a conversation with her.

ts: Yes, after the book came out. The phone rang very late one night. It was after eleven, and I answered the phone grumpily.

I hadn’t eaten dinner yet. I had just come in from work. And I said, Well, who is this? And she said, Well, I’ve been trying to reach you from Carmel, California, for a long time. And then I realized it was Doris. Everybody wants to know what it was like. We spoke for an hour; as nice as she was on the screen, she was even nicer on the phone. It’s extraordinary. She was so unbelievably honest and open; she talked about her failed marriages, her love of animals, and Hollywood. So yeah, she was pretty terrific. I wrote that book because I felt she was a huge star who never received her due.

twi-ny: She retired from movies so early in her career.

ts: Another thing in writing about Audrey Hepburn is Audrey Hepburn and Doris Day had a lot of similarities, which was they worked from when they were teenagers nonstop. And then they both walked away from their fame; Doris said, “It means much more to me to work for animal welfare.” And Audrey said, “I want to work for UNICEF.” So that interests me a lot, that in our fame-obsessed society, world-famous women would walk away from it.

twi-ny: Right. And someone like Doris Day — I bet a lot of people don’t realize that she died only in 2019. So there was a long time, even with social media and the internet and everything, that she still wasn’t around. People didn’t know her, except for her charity work, but she wasn’t flooding Facebook with it. So, she was a very private person.

ts: Yes, a very private person. And so was Audrey. And so what interests me, Mark, is we’re a fame-obsessed society today, right?

twi-ny: Oh, yes.

ts: That’s reality television, everybody demanding to be famous.

twi-ny: Even the president.

ts: That’s a really interesting dichotomy. One thing I discovered while researching the Audrey book is that who knew that Audrey Hepburn and Elizabeth Taylor were good friends? They were so opposite as people, but separately, toward the end of their lives, they used the exact same phrase: “At last, my fame makes sense to me.” And that’s because Elizabeth Taylor, with her AIDS activism, and Audrey, with UNICEF, that’s how they defined themselves. And I thought that was worth exploring.

twi-ny: That’s something that also happened and is still happening with Brigitte Bardot. She retired early to spend her life with animals and become an antifur activist. And I bet she would say the same thing as Audrey, Doris, and Elizabeth.

ts: I think that’s true. And because at a certain point, fame and money are nice, but how much does the acclaim of strangers really mean when you want to make a difference? And the difference comes through for these women through their social activism. Audrey was a kind of saint. She was such a good person.

twi-ny: All the people you spoke with, you probably never got a bad quote from anyone. Everybody just loved her. Is that right?

ts: That’s fair to say, and it’s not hyperbole. People who worked on the sets, everyone in the village in Switzerland where she lived, said she was unfailingly good to people. And I think after her war-torn, very disrupted childhood, I think she realized the value of family and the value of treating people with kindness. Because she said toward the end of her life, “The most important thing in life is being kind.” She really lived that.

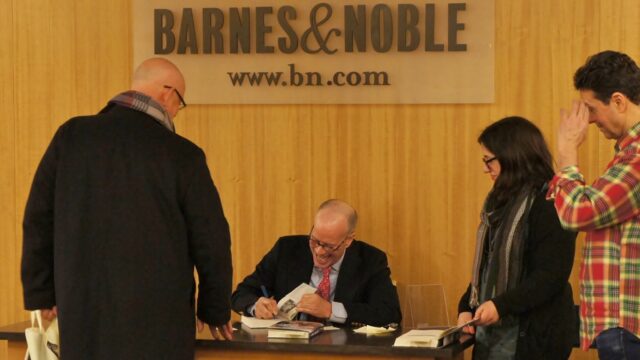

Tom Santopietro signs copies of The Sound of Music Story at B&N in 2015 (photo courtesy Tom Santopietro)

twi-ny: In doing your research and interviews, was there one moment that really struck you or surprised you?

ts: I think the biggest surprise for me is how she really — how do I want to answer this — the reason why I titled the book A Life of Beautiful Uncertainty is that her entire life, she was uncertain of herself. And that was surprising. She genuinely did not think she was pretty. She just saw flaws everywhere. She genuinely did not think she was a good actress. And that shocked me because she was beautiful. And she was a terrific actress. And I think it stems from when, in the span of two months, she won the Tony Award and the Academy Award, and her mother said to her, “It’s amazing how far you’ve gotten considering how little talent you have.” [ed. note: In 1954, Hepburn won the Tony for Ondine and the Oscar for Roman Holiday.]

twi-ny: That haunts people, that kind of stuff.

ts: Yeah. So I think it all comes back to childhood, right?

twi-ny: It so often does.

ts: Barbra Streisand grew those incredibly long fingernails because her mother said, “Well, you should be a typist.” She grew her fingernails so she couldn’t type.

I think the other thing is that because I love films, and this is circling back to what we said earlier, I felt Audrey had never received her due as to how good an actress she was. Everybody says she’s charming and beautiful, but you look at a movie like The Nun’s Story, directed by Fred Zinnemann — that is a spectacularly good performance; the whole performance is with her eyes. And I wanted people to realize how skilled she was, even if she didn’t think she was skilled.

twi-ny: One of my favorite movies, and I don’t know that it would always be at the top of her list, but I adore Charade, which you write about in the book. Even with Cary Grant, Walter Matthau, George Kennedy, James Coburn, all these popular men in the movie, it is all built around her face.

ts: That’s exactly right.

twi-ny: And it’s the best Hitchcock movie Hitchcock didn’t make.

ts: That sums up that movie perfectly.

twi-ny: Do you have a favorite film of hers?

ts: That’s a great question. I know this is a cop-out answer, but I have three favorite films: The Nun’s Story, because her performance is spectacular. And also it’s really interesting the way it grapples with issues of faith and higher powers. My second favorite movie is My Fair Lady, because it’s so beautiful to look at and listen to. And the third one is, believe it or not, Wait Until Dark, because it still scares the living daylights out of me.

twi-ny: Yes. And it’s still scaring us. People who love Alan Arkin don’t realize that he could be pretty threatening.

ts: Toward the end of his life, I was able to interview him over the phone for the book. The funny thing is, when I finally got him, he started the conversation by saying, “Well, I hear you’ve been looking for me.” What he said was that Audrey was so lovely and such a good person that twenty years later, when she received the Chaplin Award from Lincoln Center, he was one of the speakers. And when he saw her, he actually apologized to her and said, I’m so sorry I was so mean to you in that movie, which is sort of amazing.

twi-ny: Can you share publicly who or what your next subject might be?

ts: I actually haven’t really figured out who I’m writing about next because, well, this has taken a long time, but also I wrote a play and it was produced this past summer in Connecticut. So I want to spend time putting the play out in the world for other productions, and it sort of fits in with what I write about because it’s a one-woman play called JBKO, about Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis. So that’s really what I’m going to work on next.

twi-ny: Well, this is a good transition, because my last question was going to turn back to theater. You work as a house manager part-time on Broadway.

ts: Yes. I’ve been a general manager, and these days I’m working as a house manager most of the time. I don’t know if you’ve found this too, but because writing is so solitary, it’s really good for me to be around people at night at the theater. So that socialization is great, as long as the audiences are behaving themselves, of course.

twi-ny: That’s where I was going with this. At the Coffee House, we discussed how, since the pandemic, the audience’s relationship with the theater experience, interacting with other people, isn’t the same as when they were going out for a night of theater years ago.

ts: Well, I think it’s a funny thing, but since the pandemic, when people go to the theater, on some level they still think they’re in their living room streaming a show. That’s the only way I can try to make sense of it. When you’re home, you talk, you eat. And it’s different in a Broadway theater. So that’s sort of my best explanation for it.

twi-ny: Right. As someone who goes to a lot of theater, I’ve seen some things that I never had before. It’s like, I paid for my ticket, I can do whatever I want. But no, you can’t. It’s sort of representative to me of how we deal with our fellow human beings in everyday life. Now we’re much more quickly agitated, and people don’t want anyone telling them what to do.

ts: Exactly. Yeah, that has all changed. What hasn’t changed, the positive thing for me, is that theater offers people the sense of being part of a family. Everybody’s there backstage to put on the best possible show. I always say you belong when you walk through the stage door. And that’s a great feeling. That’s the joy of theater for me.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]