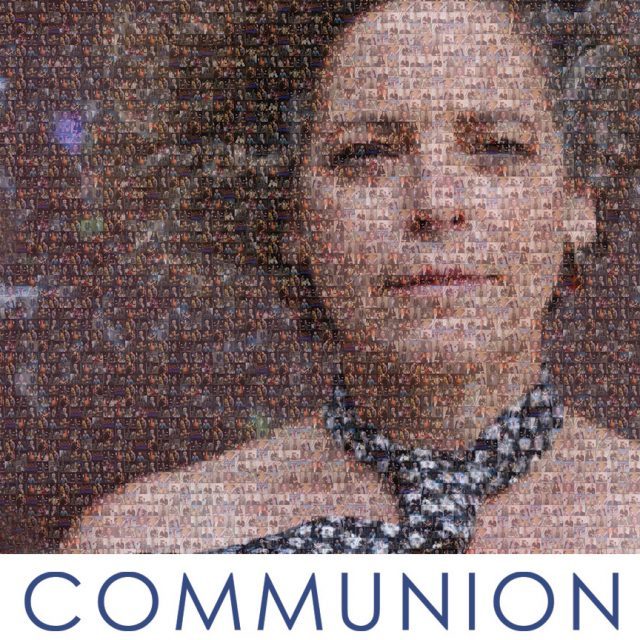

Who: Anne O’Riordan

What: One-woman online play

Where: #IrishRepOnline

When: Through July 4, free with RSVP (suggested donation $25)

Why: The Irish Rep continues to be the most consistently innovative and creative company on the planet during the Covid-19 crisis with Anne O’Riordan and Jamie Beamish’s Ghosting, its latest “performance on screen.” The one-woman show debuted in London and made its Irish premiere at Theatre Royal in Waterford in 2019; O’Riordan returned to that stage in April 2020 for a livestreamed production that is now available on demand through July 4 via the Irish Rep, in conjunction with Throwin Shapes. O’Riordan plays Sí, a young Irish woman working in London when a strange visitor materializes in her apartment in the middle of the night. “I lie in bed and think. I know no one likes that these days but it’s ok to be on your own, with just your thoughts,” she tells us early on. “I like it. In the dark. No lights, no sound, no one to annoy me. You can lie there and hold your breath and wonder; is this it? Is this what it will be like to be dead? That’s all I was doing last night, the same thing I’ve done every night since I came to London five years ago. I was lying there awake, on my own. That’s fine sure. Who else do I want? Who else do I need? I don’t need anyone else in my life. I was thinking that exact thought last night when I realised that someone was in the bedroom with me.”

It turns out to be Mark Kelly, her onetime boyfriend who had ghosted her six years before, suddenly refusing to see her or speak with her, with no explanation. The next morning, Sí gets a text from her sister, Aisling, letting her know that Kelly died two days before. Sí says, “I feel a huge knot in my stomach. I don’t know why I’m even remotely bothered, sure he’s been dead to me for six years. He’s been blocked out of my mind for . . . well, until last night. When he . . .” At the spur of the moment, she decides to fly back home to attend the funeral, going back to her sister and father and hometown that she has been ghosting ever since she left for London. Once there, she learns more about her family and Kelly, complicating her situation and providing just as many questions as answers.

The seventy-five-minute play was written by O’Riordan and Beamish, who also serves as director, composer, and sound and projections designer, with lighting by Dermot Quinn and live video editing by Seán O’Sullivan. O’Riordan (Call the Midwife, Doctors) traverses the dark, empty set, the camera sometimes coming in for a close-up, then pulling back for a longer shot as if we’re sitting in the audience, which is empty. The projections take us from Sí’s office, the airport, and a smokey bar to a funeral home and the beach as Sí deals with a London colleague she calls Hobbit Tom; Laura, a high school acquaintance; the tall Lorcan, who works at the funeral parlor; and Mark’s mother, who has a surprising story to share. All the while, Sí considers whether she should see her father for the first time in what has been too long.

O’Riordan is mesmerizing as she examines her life not unlike how many of us have done over the last year and a half, as the coronavirus pandemic shuttered us in our homes, eliminated public gatherings, kept us far from loved ones, and was the cause of too many funerals. “We never really go away, do we?” the lonely Sí asks. “There’s always something left behind. Never mind them ghosts. I don’t believe in them anyway.” But with plays like Ghosting, we can still believe in the power of theater to help us face the world and get through the darkness.