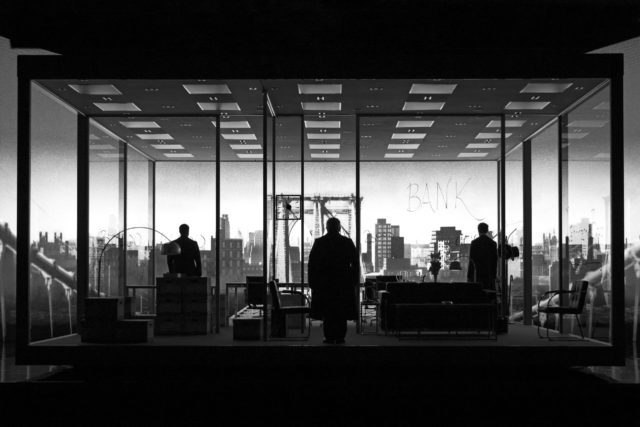

Irish Rep revival of The Streets of New York shines a light on greed, poverty, and the power of love (photo by Carol Rosegg)

THE STREETS OF NEW YORK

Irish Repertory Theatre, Francis J. Greenburger Mainstage

132 West 22nd St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Wednesday – Sunday through January 30, $50-$70

212-727-2737

irishrep.org

As the pandemic lockdown lifted and the city opened back up, Irish Rep artistic director Charlotte Moore decided to revisit the company’s 2002 hit, The Streets of New York. “In this time of Covid, I was sure it would be appropriate to rewrite my original director’s note,” Moore explains in the program. “But upon rereading the original, so many things are exactly the same that I have changed my mind. There is still great poverty and hunger, and the heartbreak of lost love never changes. Add to that a worldwide pandemic and a masked society and Boucicault’s eighteenth-century world seems to fit right into our twenty-first with its darkness and restrictions.”

Moore adapted Dublin-born Dion Boucicault’s 1857 play The Poor of New York, itself based on Édouard Louis Alexandre Brisebarre’s Les Pauvres de Paris, adding more than a dozen songs to the Dickensian tale of greed and hardship. The result is a delightful, indelible tale that feels just right for this moment in time, one that I can envision becoming an annual holiday tradition.

The show begins on the eve of the Panic of 1837, which led to an economic depression. “The poor man’s home is a filthy street / You sell your shoes for a scrap of meat,” a man sings. An older couple adds, “The violence of poverty breeds everywhere / And a cloud of injustice hangs in the air/ And till it clears / It could be years / But till it clears / We must survive / And stay alive / On these unholy, shadowy, crime ridden, black hearted, / Blood sodden, filthy, mean / Streets of New York!”

Wealthy banker Gideon Bloodgood (David Hess) is preparing to abscond with his Nassau St. bank’s money when sea captain Patrick Fairweather (Daniel J. Maldonado) arrives after hours to entrust Bloodgood with his life savings before going on a voyage, seeking the banker’s protection of the financial security of his wife and two children. Fairweather departs but returns moments later, changing his mind and demanding his fortune back. But the greedy Bloodgood is not about to surrender his newfound gains, and when Fairweather suddenly drops dead, Bloodgood decides to dump the body and keep the money — but not before one of his clerks, Brendan Badger (Justin Keyes), grabs the signed deposit receipt, hiding it away for a rainy day.

The Puffy family (Polly McKie, Richard Henry, and Jordan Tyson) find a way to smile amid their drudgery in The Streets of New York (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Twenty years later, Bloodgood, accompanied by his ever-faithful butler, Edwards (Price Waldman), is basking in his vast success, built on the cash he stole from Fairweather. While Bloodgood is looking for a suitable husband for his spoiled daughter, Alida (Amanda Jane Cooper), Fairweather’s children, Lucy (DeLaney Westfall) and Paul (Ryan Vona), and widow, Susan (Amy Bodnar), are living in abject poverty in the dangerous area of New York City known as Five Points. Their poor but goodhearted landlord, Dermot Puffy (Richard Henry), has fallen behind on his mortgage payments, so the heartless Bloodgood threatens to evict Puffy, his wife, Dolly (Polly McKie), and their daughter, Dixie (Jordan Tyson), which would leave the Fairweathers homeless as well.

The Fairweathers hope to be saved by Lucy’s childhood love, Mark Livingstone (Ben Jacoby), scion of a well-heeled, prosperous society family, while Alida plots to marry Mark herself to restore the Bloodgood name to respectability even as she fools around with the philandering Duke Vlad (Maldonado). Like her father, it’s only money and appearances that matter. “Isn’t it wonderful to be in control / Who cares if Daddy has to sell his soul / To keep me in accoutrements / To keep me in the things I want / To keep me happy,” Alida selfishly admits. “Allowed to be horrid and rude to everyone / A sense of entitlement is so much fun / I ride whilst poorer people walk, (with a frown) or run! / Oh! How I love being rich!”

As Christmas approaches, some are destined to be showered with yet more wealth while others seem bound for anonymity, struggling to survive day by day in the perilous gutters of an uncaring metropolis. The very best kind of mustache-twirling melodrama ensues as the plot leaps and twists to its conclusion.

Robber baron Gideon Bloodgood (David Hess) and his obnoxious daughter (Amanda Jane Cooper) boss around their butler (Price Waldman) in The Streets of New York (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Moore, who with Irish Rep producing director Ciarán O’Reilly created some of the most compelling and innovative online shows during the pandemic, goes back to the basics with The Streets of New York. Linda Fisher’s period costumes feel authentic, and Hugh Landwehr’s set, covered with giant bills and help wanted ads, is centered by a large wall that the actors and masked staff members move around, magically morphing into the Bloodgoods’ opulent home and office as well as doomed tenements in Five Points.

The five-piece orchestra is partially visible offstage right, consisting of Melanie Mason on cello, Jeremy Clayton on woodwinds, Karen Lindquist on harp, Sean Murphy on bass, and Joel Lambdin on violin, performing lovely orchestrations by music director Mark Hartman and associate conductor Yasuhiko Fukuoka.

Two-time Tony nominee Moore, who previously directed Boucicault’s London Assurance in addition to plays by O’Casey, Yeats, Friel, and Synge and such musicals as Meet Me in St. Louis and Love, Noël: The Letters and Songs of Noël Coward, gives ample room for the material, which often evokes operetta, to breathe on the cramped stage, the two and a half hours (with intermission) never slowing down for a minute. Moore’s lyrics do what they’re supposed to, help develop the narrative and give depth to the characters; nary a word is extraneous. Barry McNabb’s choreography shines in the vaudevillian duet “Villains,” a riotous showstopper featuring Hess and Keyes. Cooper brings down the house in her engaging solo, “Oh, How I Love Being Rich,” her obnoxious coquettishness channeling Bernadette Peters and Kristen Chenoweth. (She’s worked onstage with Chenoweth several times.) Hess stands out as the scoundrel Bloodgood, reveling in his egomaniacal affairs, while Jacoby is heart-wrenching as a man who just wants to do the right thing but is thwarted at every turn.

Still caught up in a pandemic and social justice movement that have magnified the sorry state of income inequality in America, The Streets of New York doesn’t feel old-fashioned as much as fresh and prescient. We all want a “taste of the good life,” as the Puffys explain, but it’s not always within reach. However, the power of love — and a delightful musical — has the ability to transcend suffering and bring light to lead us out