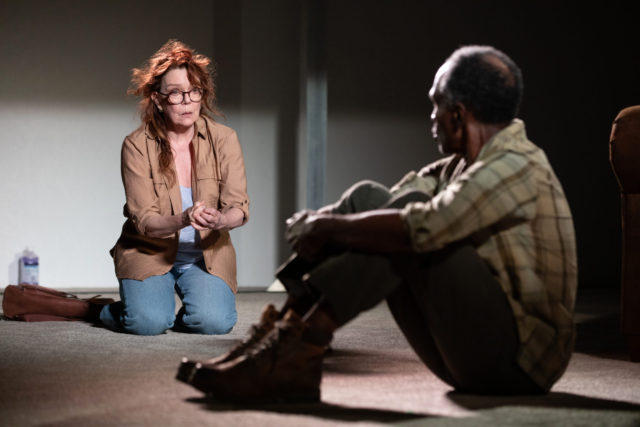

Joe Cordaro and John Harlacher star in Timothy Haskell’s semibiographical play about Jean Claude Van Damme (photo by Nathaniel Nowak)

THE RISE AND FALL, THEN BRIEF AND MODEST RISE FOLLOWED BY A RELATIVE FALL OF . . . JEAN CLAUDE VAN DAMME AS GLEANED BY A SINGLE READING OF HIS WIKIPEDIA PAGE MONTHS EARLIER

The Pit Loft

154 West Twenty-Ninth St. between Seventh & Eighth Aves.

Friday – Sunday through July 17, $24.99 with discount code JCVD22, 7:30

thepit-nyc.com

I’ve seen so many meticulously researched plays about real-life figures and situations, wondering what is actually true and what has been tweaked — or just plain made up — for dramatic effect, that Timothy Haskell’s new work is a breath of fresh air. The title explains exactly what you’re in for: The Rise and Fall, Then Brief and Modest Rise Followed by a Relative Fall of . . . Jean Claude Van Damme as Gleaned by a Single Reading of His Wikipedia Page Months Earlier. Haskell checked out Jean Claude Van Damme’s relatively lengthy Wikipedia entry, then, a few months later, wrote a play based only on what he could remember, without doing any further reading or fact checking. “Absolutely no research was put into learning anything about the subject at hand,” we are told early on. “It was all gleaned from one cursory glance at his Wikipedia page, and just general knowledge of the man based on tabloid headlines.”

The result is a breezy, extremely funny look at fame, ambition, gossip, and celebrity, gleefully codirected by Haskell, set designer Paul Smithyman, and puppet master Aaron Haskell (Timothy’s brother). For about an hour at the Pit Loft, John Harlacher and Joe Cordaro, standing behind makeshift podiums, share the not-necessarily-true story of the Muscles from Brussels. Between them is an angled table with slots where they place cardboard cutouts on Popsicle sticks of Van Damme and people who have been part of his personal life and professional career — or have nothing to do with him. Behind them is a small “screen” on which they project photos and a few choice film clips, including a fantastic moment from 1984’s Breakin’ with Van Damme as an uncredited background extra.

Both actors play multiple roles, but the hirsute Harlacher (Bum Phillips, Dog Day Afternoon) is mainly the narrator, meandering through his overstuffed, disorganized notebook, while Cordaro (The Foreigner, The Tiny Mustache) is mostly the former Jean-Claude Camille François Van Varenberg, reacting to what the narrator says and occasionally taking center stage to act out various scenes, including JCVD’s infamous barfight with Chuck Zito.

Timothy Haskell and the narrator make no bones about what went into the scattershot though chronological show, which has a proudly middle school DIY aesthetic. Introducing the Breakin’ clip, the narrator explains, “There’s a pretty fun YouTube remix our author was lucky enough to stumble upon while limply researching another play about the movie Breakin’ that some guy did that looks like this.” The two actors dance along with JCVD, after which the narrator rhetorically asks, “Isn’t that fun?” Yes it is!

Repurposed action figures play a pivotal role in JCVD show at the Pit Loft (photo courtesy Aaron Haskell)

Commenting on JCVD’s battle with drugs, the narrator admits, “As for Jean Claude, he did that stupid thing in Breakin’ and then toiled away some more and did a ton of bullshit and got all kinds of high. Not on life either, brother. The man was a straight up smack head if smack head means you did lots of cocaine which the author is now not sure it does. Fed up and high as a Romanian glue-huffer he decided to make some bold moves. He decided to case Joel Silver’s office. Joel Silver was the producer of Road House starring Patrick Swayze that was later turned into a hit play by Timothy Haskell who thought after that he could do serious work but was wrong.”

As JCVD’s career rises and falls and rises and falls and so on, we (sort of) learn about his siblings, his wives, his martial arts mentors and heroes, his perhaps partially fabricated tournament record, and his hotly anticipated confrontation with Steven Seagal. We go behind the scenes of such films as Bloodsport, Kickboxer, Universal Soldier, and Timecop. Oh, and there is plenty of fighting, carried out by Cordaro and Harlacher with repurposed action figures, designed by Aaron Haskell, battling it out on a long, narrow fencing piste at the front of the stage. It’s like watching two young friends playing in the basement with their GI Joe dolls — the ones with kung fu grip, of course.

As a founding member of Psycho Clan, Haskell has presented such immersive horror experiences as This Is Real, Santastical, and I Can’t See. He has also directed James and the Giant Peach, Fatal Attraction: A Greek Tragedy, Road House: The Stage Play, and the upcoming graffiti drama Hit the Wall.

In an April 2014 twi-ny talk about his interactive Easter-themed eggstravaganza, Full Bunny Contact, I asked him, “What happened to you as a child? Based on the kinds of shows and events you write, produce, direct, and create, there had to be some kind of major trauma involved.” He replied, “Nothing unusual. My mother says she dropped a toy Ferris wheel on my head, and anytime I do something unusual she blames herself for dropping a heavy toy on my noggin.” That could explain this new work as well.

The show concludes with an extended monologue by JCVD, who begins by warning, “I know what happened. I am me. I don’t need to read a Wikipedia page to know who I am. I did, however. Thoroughly. Ya know, for safety.”

There’s nothing safe about The Rise and Fall, Then Brief and Modest Rise Followed by a Relative Fall of . . . Jean Claude Van Damme as Gleaned by a Single Reading of His Wikipedia Page Months Earlier. But there is a whole lot that is hilariously entertaining. And that person sitting behind you, laughing even harder than you, just might be Timothy Haskell himself.