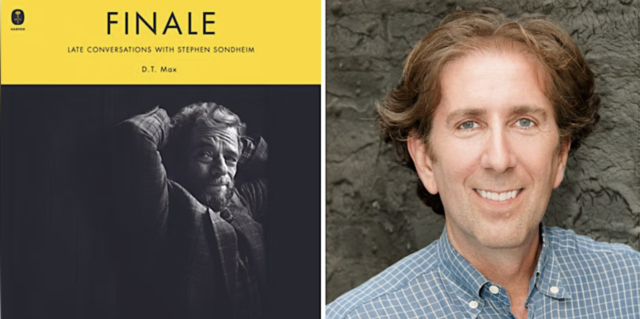

A cast of five extraordinary women share roles in Quiara Alegría Hudes’s My Broken Language (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

MY BROKEN LANGUAGE

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through November 27, $49-$159

212-244-7529

www.mybrokenlanguage.net

Quiara Alegría Hudes’s My Broken Language is an exhilarating ninety minutes of love and loss among a close Puerto Rican family in North Philly over the course of sixteen years.

During the pandemic, Hudes, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for her play Water by the Spoonful, about an Iraq War veteran returning to his home in Philadelphia, published a memoir, My Broken Language, detailing her childhood from 1988, when she was ten, to 2004, when she went to the Brown University Grad School for Playwriting. The book is divided into four parts: “I Am the Gulf between English and Spanish,” “All the Languages of My Perez Women, and Yet All This Silence . . . . ,” “How Qui Qui Be?,” and “Break Break Break My Mother Tongue.” At a public reading, Hudes, also known as Qui Qui, invited a group of actors to read different chapters, which sparked the development of the book into a play with multiple women sharing the lead role. The stirring result is at the Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre at the Signature, where it opened tonight for a limited run through November 27. Get your tickets now.

The audience sits on three sides of Arnulfo Maldonado’s beautifully bright, intimate set, a tiled courtyard with three porcelain bathtubs filled with plants, a shower, and steps leading to the door of a house with a facade of two long rows of windows, behind which is greenery, as if life is growing inside. Tucked next to the steps is a piano where Ariacne Trujillo Duran occasionally plays Chopin and original music by Alex Lacamoire.

The play, which Hudes calls “a theater jawn,” begins with Zabryna Guevara, Yani Marin, Samora la Perdida, Daphne Rubin-Vega, and Marilyn Torres declaring in unison, “My Broken Language. North Philly. 1988. I’m ten years old.” Each “movement” of the jawn kicks off with similar declarations as time passes, with a different actor taking over the lead role of Qui Qui, complete with singing, dancing, and poignant and prescient monologues; the rest of the cast play other roles as well.

Daphne Rubin-Vega plays the ten-year-old author in Signature world premiere (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

“Cousinhood in my big-ass family was a swim-with-the-sharks wonderland,” ten-year-old Qui Qui says on the way to an amusement park in New Jersey. “When Cuca invited me to Six Flags with the big cousins, I was Cinderella being invited to the ball. These weren’t the rug rats of the family, my usual crew. Five to ten years my elder, my big cousins were gods on Mount Olympus, meriting study, mythology, even fear.” A moment later, she adds, “Cuca, Tico, Flor, and Nuchi. Saying their names filled me with awe. They had babies and tats. I had blackheads and wedgies. They had curves and moves. I had puberty boobs called nipple-itis. They had acrylic tips in neon colors. I had piano lessons and nubby nails. They spoke Spanish like Greg Louganis dove — twisting, flipping, explosive — and laughed with the magnitude of a mushroom cloud.”

As 1988 becomes 1991 in West Philly, 1993 in North Philly, 1994 in Center City, 1995 back in West Philly, and 2004 in Providence, Qui Qui, identified as “Author” in the script, has her period, is fascinated by her mother’s mysterious Yoruba religious rituals, discovers great literature (Flannery O’Connor, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Sandra Cisneros, Esmeralda Santiago) and art (Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2, Fountain), and learns too much too quickly about death.

“One day I would dream of a museum, a library I might fit into. One with space to hold my cousins, my tías, my sister, mi madre. An archive made of us, that held our concepts and reality so that future Perez girls would have no question of our existence or validity,” sixteen-year-old Qui Qui fantasizes. “Our innovations and conundrums, our Rashomon narratives could fill volumes, take up half a city block. Future Perez girls would do book reports amid its labyrinthine stacks, tracing our lineages through time and across hemispheres. A place where we’d be more than one ethnic studies shelf, but every shelf, the record itself. And future Perez girls would step into the library of us and take its magnificence for granted. It would seem inevitable, a given, to be surrounded by one’s history.”

That soliloquy gets to the heart of My Broken Language, which is an inclusive celebration of who the Perez family is and what they can be. Despite the constant adversity, Hudes focuses on the individuality of the characters and the author herself, portrayed by five distinct women who represent the vast range of Puerto Rican women, in mind and body, washing away ethnic and gender stereotypes. Even as “asterisks” point out future tragedy, the play is life-affirming as the actors stand firm and bold, singing Lacamoire’s “La Fiesta Perez” and “Every Book, a Horizon,” Ernesto Grenet’s “Drume Negrita,” and Joni Mitchell’s “Hejira” and moving to Ebony Williams’s engaging choreography in Dede Ayite’s colorful, dramatic costumes that trace the development of young women. (Yes, that’s Daphne Rubin-Vega in pigtails!)

Tiled bathtubs figure prominently in My Broken Language (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

In her directorial debut, Hudes allows each actor the freedom to incorporate their own realities into their characters, including a wonderful moment in which all five line up on the steps and, one by one, grab the person next to them in their own way. Although a scene about Qui Qui’s favorite books feels didactic — the listing in the digital program, which also includes a glossary of terms and pop-culture references, would have sufficed — everything else flows together organically, immersing the audience in the story of the Perez family. Jen Schriever’s lighting never goes completely dark, allowing the audience to see the actors, the actors to see the audience, and audience members to see themselves, all part of an intimate, caring community.

The cast, led by the fabulous Rubin-Vega, who has also appeared in Hudes’s Daphne’s Dive at the Signature and Miss You Like Hell at the Public, and Guevara, who starred in the playwright’s Water by the Spoonful at Second Stage and Elliot, a Soldier’s Fugue at 45 Below, revels in the flexibility Hudes gives them; in the script, she notes, “No need for them to act, speak, or move like one cohesive character. The point is a multiplicity of voices, bodies, and vibez.” That advice works for the audience as well, during the play and as they exit back into real life.

[On November 13 at 5:00, the Bushwick Book Club will hold a special free event at the Signature, hosted by Guevara and featuring readings from Hudes’s memoir along with original music and movement by spiritchild, Patricia Santos, Anni Rossi, Susan Hwang and Troy Ogilvie.]