Kimberly (Victoria Clark) and Seth (Justin Cooley) become good friends in Kimberly Akimbo (photo © Joan Marcus)

KIMBERLY AKIMBO

Booth Theatre

222 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 26, $84 – $419

kimberlyakimbothemusical.com

Broadway shows about death and dying tend to be serious affairs. Plays such as The Shadow Box, Marvin’s Room, Angels in America, ’night, Mother, and Whose Life Is It Anyway? are not lighthearted comedies; Wit is not exactly a laugh riot. (By the way, those six works have four Pulitzers between them.) But right now, Mike Birbiglia is facing his own mortality every night in his hilarious one-man show The Old Man & the Pool, at the Vivian Beaumont, while Kimberly Akimbo, an unusual, life-affirming musical about a high school girl with a terminal illness, is delighting audiences at the Booth.

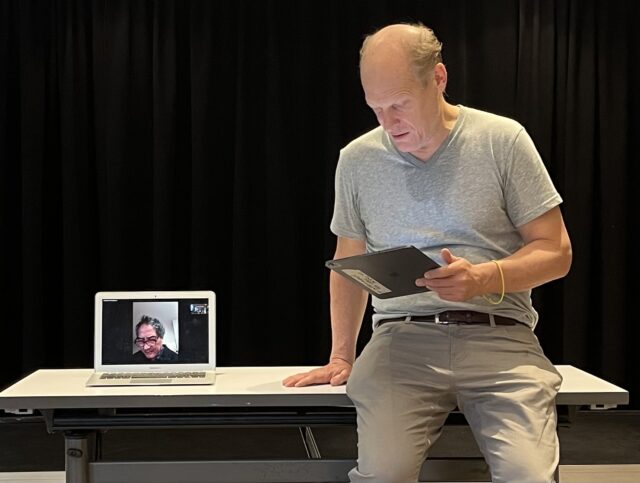

Making a smooth transition from its fall 2021 debut at the Atlantic, Kimberly Akimbo is the must-see musical of the season. Adapted by Pulitzer winner David Lindsay-Abaire from his 2000 play of the same name, the show tackles how awkward kids can be during their teen years, as evidenced by the title. Kimberly Levaco (Victoria Clark), who is approaching her sixteenth birthday, becomes friends with super-nerd Seth (Justin Cooley), who is obsessed with anagrams; rearranging the letters in her name, he rechristens her Cleverly Akimbo. The show, the character, and Clark are all that and more.

Kimberly has an extremely rare genetic disorder, similar to progeria, in which she ages at four or five times the normal rate. Most girls look forward to turning sweet sixteen, but for Kimberly, she would be nearing the equivalent of eighty; she is magnificently portrayed by Tony winner Clark, who is sixty-three but infuses the part with a glorious enthusiasm and affection for life and what it offers, living every minute to its fullest, understanding it could — and will — all be over at any second.

Kimberly’s mother, Pattie (Alli Mauzey), is pregnant, stuck at home with carpal tunnel in both hands and making videos for her unborn child. “There’s a high probability that I might be dead soon. / So I won’t be around when you’re growing up, / and this video is the only way for you to know who I was. / And I want you to know who I was because / people are going to tell you things about me that just aren’t true,” she sings insensitively, bringing up her own potential death and focusing on her fetus instead of paying attention to Kimberly, who really is dying and might never get to meet her sibling.

Kimberly’s father, Buddy (Steven Boyer), is a low-level gambler and drinker who works at a gas station and does not know how to express love for his daughter; he’s still too much of a child himself. “I should be happy for her,” he sings when she makes a new friend, but he doesn’t know how. “I should be happy.” Later, he says, “I never pictured myself a father. I mean, I like kids, I just . . . I’m more of a bachelor uncle type.” He is more excited than Kimberly when he wins a Game Boy in a bet.

Kimberly (Victoria Clark, center) has issues with her parents (Alli Mauzey and Steven Boyer) in Broadway musical (photo © Joan Marcus)

Kimberly teams up with Seth for their sophomore bio class project, in which they have to explore a disease. Seth wants to use Kimberly’s condition, but she’s not so sure. Meanwhile, the quartet of Delia (Olivia Elease Hardy), Martin (Fernell Hogan), Aaron (Michael Iskander), and Teresa (Nina White) is pairing up for the project and preparing for Show Choir, a competition against other schools. In a fab subplot, they are also trying to figure out how to pair up relationship-wise, not quite knowing yet who’s gay or straight and who likes who.

They are planning on performing a medley from Dreamgirls.. It’s no accident that Lindsay-Abaire chose that particular musical, whose title song begins, “Every man has his own special dream / and your dream’s just about to come true / Life’s not as bad as it may seem if you / open your eyes to what’s in front of you.” High school kids are supposed to dream about the future, but Kimberly is running out of time. Meanwhile their main rival, West Orange, is doing Evita, a musical about Argentinian leader Eva Perón, whose life was cut short by cancer at the age of thirty-three.

Everything goes even more akimbo when Buddy’s sister, Debra (Bonnie Milligan), the black sheep of the family, arrives unexpectedly; the Levacos had escaped Lodi to get away from Debra, who has a penchant for breaking the law with a greedy selfishness and spending time in the hoosegow. She has a master plan involving bank fraud and a stolen US mailbox — itself a funny prop because the younger generations today mainly think of them as relics in the age of social media and texting, similar to pay phones — and attempts to get Kimberly, Seth, Delia, Martin, Aaron, and Teresa to help her with the scheme.

As Kimberly’s sixteenth birthday approaches, the cleverly askew storylines all come together for a poignant finale.

Debra (Bonnie Milligan) finds a crew to attempt a heist in Kimberly Akimbo (photo © Joan Marcus)

Kimberly Akimbo is about much more than a teen with a horrible disease; it’s a spectacularly insightful depiction of the joys and fears that teens experience, at school and at home, with friends and family, as they mature into young adults. Kimberly has an illness that strikes only one in fifty million people — meaning only seven people in the United States might have it — but she represents us all, children and grown-ups. Lindsay-Abaire’s (Rabbit Hole, Ripcord) book and lyrics capture the exhilarating highs and the devastating lows that are parts of everyday life, which is like an endless series of anagrams we try to unravel; when Pattie says, “I hate getting old,” she’s not just speaking for herself. And when she shares her anxiety over having another baby and Kimberly declares, “Scared it would be like me?,” it’s a feeling many can relate to. As Kimberly sings in “Anagram”: “With a change of perspective . . . ha-ha-ha-ha . . . / nothing’s defective / I wonder what you see / when you look at me.”

Tony winner Jeanine Tesori’s (Fun Home, Caroline, or Change) score matches the ups and downs of the plot, from the tender piano of “Anagram” to the jubilance of “Skater Planet” and “This Time,” with playful choreography by Danny Mefford (how do they ice skate like that?), realistic costumes by Sarah Laux, and terrific sets by David Zinn that range from a suburban skating rink to a high school hallway to the Levaco living room.

Mauzey (Wicked, Cry-Baby) and Boyer (Hand to God, Time and the Conways) are terrific as Kimberly’s parents, who attempt to navigate through what for them is also a traumatic situation, knowing their teenage daughter will not be with them much longer, while Jimmy Awards finalist Cooley excels as the awkward but determined and hopeful Seth, and Milligan (Head Over Heels, Gigantic), as a thief, essentially steals every scene she’s in.

But the centerpiece of the show is the unforgettable performance by Clark (Gigi, Sister Act), who won her Tony for The Light in the Piazza before most of the rest of the cast members were born, or were mere babes. Her every movement and gesture, her voice, and, most critically, her bright, searching eyes will have you convinced she is a fifteen-year-old high school student carrying all the requisite baggage — while also knowing that any day could be her last. But the show is not about aging and death; it’s an infectious celebration of life.

At one point, Martin says, “Who cares? It’s not like any of this counts.” Seth responds, “What do you mean?” Martin answers, “I mean, high school. This town. It’s not even real life. It’s just the crap you have to get through before you get to the good part.” Teresa chimes in, “And what’s the good part?” Martin answers, “Um, the rest of our lives?” Kimberly Akimbo makes it clear that right now is the good part, no matter how long the rest of your life is.