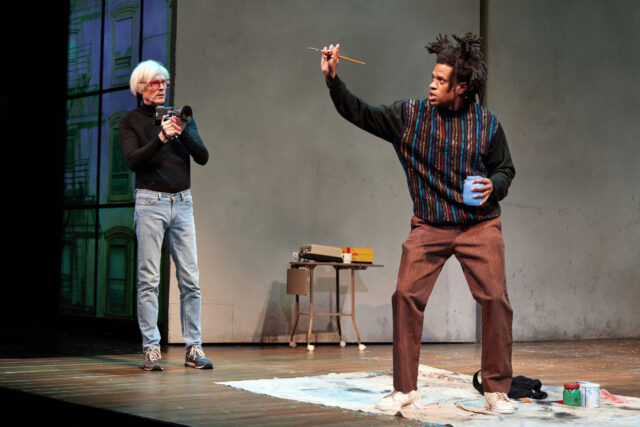

Norbert Leo Butz heads a strong cast in Simon Stephens and Mark Eitzel’s Cornelia Street (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

CORNELIA STREET

Atlantic Stage 2

330 West 16th St. between Eighth & Ninth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 5

atlantictheater.org

It’s a problem we know all too well: beloved New York City restaurants closing because of financial issues, primarily rising rents. During the pandemic, dozens and dozens of dining establishments, from Beyoglu, Blue Smoke, the ‘21’ Club, and Feast to Jewel Bako, Lucky Strike, the Mermaid Inn, and Mission Chinese, shut their doors because of rent as well as food costs and supply chain issues.

But it doesn’t take a worldwide health crisis to affect a restaurant’s longevity. In January 2019, the Cornelia Street Café, a West Village treasure since 1977, closed over rent increases. “I am sad to say that I am losing my oldest child,” cofounder Robin Hirsch wrote. “Cornelia has brought me both joy and pain, and it is with a broken heart that I must bid her adieu.”

Tony and Olivier winner Simon Stephens was inspired by the Cornelia Street Café in writing Cornelia Street, a rousing yet intimately touching musical that opened last night at Atlantic Stage 2. It is not specifically about the restaurant and downstairs performance venue that was located on Cornelia St. between Bleecker and West Fourth Sts., but Stephens spent time at the café in 2018 doing research for the work, which features music and lyrics by American Music Club founder Mark Eitzel; the two have previously collaborated on Marine Parade and Song from Far Away.

The show is set in the present day inside Marty’s Café, a local haunt that has been on Cornelia St. in the West Village for decades. The building is about to be put up for sale, so Marty and his longtime chef, Jacob (Norbert Leo Butz), are preparing to convince the Realtors and investor Daniel McCourt (Jordan Lage) that their restaurant is worth keeping. While Marty is extremely concerned about the balance sheets, the Jersey City-born Jacob thinks that a menu revamp is the way to go, consisting of higher-end dishes with classier ingredients: venison ravioli, pizza with Spanish chorizo, omelets with porcini mushrooms.

Jacob has been working at Marty’s for twenty-eight years; he and his fifteen-year-old daughter, Patti (Lena Pepe), who is having trouble at school, live above the café. Philip (Esteban Andres Cruz) is the waiter/bartender, a struggling actor having difficulty getting auditions.

Jacob (Norbert Leo Butz) takes a closer look at his daughter, Patti (Lena Pepe), in world premiere at Atlantic Stage 2 (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

Three regulars come to the café to eat and/or drink nearly every day: John (Ben Rosenfield), a sweet, innocent computer scientist in his late twenties; Sarah (Mary Beth Peil), a retired opera singer who might be able to see the future; and William (George Abud), a perpetually nasty taxi driver and dealer who is always looking over his shoulder.

Jacob is shocked by the unexpected arrival of Misty (Gizel Jiménez), the daughter of an old girlfriend who he helped raise for a time. Misty is broke, alone, and angry, so Jacob gives her a job and lets her sleep in Patti’s room.

When Jacob is offered an opportunity to make some fast cash, relationships grow more complicated and trouble looms. As Sarah says somewhat facetiously, “There is a patisserie on the corner of Carmine and Sixth that is selling Edie Sedgwick cupcakes. This is a city that has started to eat itself.”

Scott Pask’s welcoming set makes the audience feel right at home, as if we are sitting at our own tables at the café. The wooden bar is at stage left, a few round tables stage right, and a window at the back that reveals the dark, narrow street outside. Linda Cho’s costumes are basic café wear, comfortable outfits, although Jacob’s concerts tees (the Ramones, Ziggy Stardust) spark a contrast with William’s flashy $240 shirt.

As opposed to being an all-out musical, Cornelia Street is more of a play with songs. Stephens’s (Heisenberg, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time) book is smart and thorough, although there are two key moments that very well could have gone the wrong way but he rights the ship in time. Eitzel’s music is based in pop with lovely orchestrations by John Clancy, featuring Alec Berlin on guitar, Kirsten Agresta-Copley on harp, Gina Benalcazar on trombone, Marcos Rojas on tuba, Emma Reinhart on reeds, and Michael Ramsey on percussion and triangle. Part of the band is visible onstage, while the rest is nearly hidden off to the sides.

John (Jordan Lage) looks on as Jacob (Norbert Leo Butz) and Misty (Gizel Jiménez) go at it in Cornelia Street (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

The choreography, by former Alvin Ailey standout dancer Hope Boykin (Beauty Size & Color), is playful and appropriate, helping define who the characters are and what they want out of life. Each actor moves to their own groove, from a sweet shuffle to an elegant twist. No one is trying to tear the roof off the house, which matches the tempo of the narrative; there is no excess, a meal served with just the right ingredients.

However, Eitzel’s lyrics are a letdown, too often getting caught up in clichés even when successfully developing the characters and their relationships with one another. “So I’m saying this with a loving heart / Don’t be clever just be smart / Get A’s in science get A’s in art / And you will own the world,” Jacob assures Patti. “Loving an angel is bad / For your liver / For them nothing gets old / But the love of an angel nothing is better / In their arms you don’t feel the cold,” Sarah declares. One of the only times I lost focus was when Jacob tells himself, “If there’s a chance / I’m gonna take it / And if there’s a chance / I’m gonna make it,” which made me think of the late Cindy Williams and the theme song from Laverne and Shirley.

Tony-nominated director Neil Pepe, the Atlantic’s artistic director who has helmed such productions as Hands on a Hardbody, American Buffalo, and Stephens’s On the Shore of the Wide World, guides it all with expert precision; the characters don’t break out into song, stopping the play’s progression, but instead seamlessly continue the plot.

The excellent cast is led by two-time Tony winner Butz (Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, My Fair Lady), who plays Jacob with a gruff, heartfelt soul; you can’t take your eyes off him when he’s onstage (which is virtually the entire 140-minute show, with intermission). Jiménez (Miss You Like Hell, Tick, Tick . . . Boom!) is appealing as the dark, mysterious Misty, Rosenfield (The Nether, Love, Love, Love) is adorable as the uncomplicated John, Tony nominee Peil (A Man of No Importance, Anastasia) is a delight as the lovely Sarah, and Lena Pepe, Neil’s daughter, is impressive in her off-Broadway debut.

On February 13 at 7:00, the Atlantic hosted the special event “Stories from the Cornelia Street Café,” an evening of songs and stories with Hirsch, Stephens, and Eitzel. We might not have the café itself anymore, or so many other cherished restaurants, but we do have this terrific show to satiate at least part of our thirst and hunger.