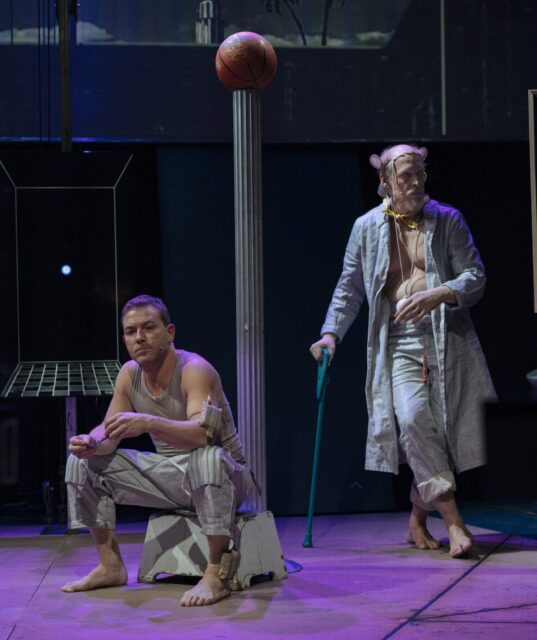

The Who’s Tommy is back on Broadway in a bewildering revival (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

THE WHO’S TOMMY

Nederlander Theatre

208 West Forty-First St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through July 21, $89.75-$319.50

tommythemusical.com

Watching Lempicka at the Longacre, where it just announced an early closing date of May 19 — it was scheduled to run until September 8 — I was struck by how similar it was to The Who’s Tommy, which is packing them in at the Nederlander.

Each show focuses on a unique title character — one a fictional “deaf, dumb, and blind kid” who has been part of global pop culture since 1969, when the Who’s rock opera was released, the other a far lesser known real Polish bisexual painter named Tamara Łempicka, who was born in Warsaw in 1898 and died in Mexico in 1980.

Both musicals were presented at La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego prior to opening on Broadway, both involve world wars and fighting fascism, both feature ridiculously over-the-top choreography, and both use empty frames as props that detract from the protagonist’s creative abilities. And as a bonus coincidence, Jack Nicholson, who portrayed the specialist in Ken Russell’s 1975 film adaptation of Tommy, is a collector of Lempicka’s work, having owned Young Ladies and La Belle Rafaela.

While there are elements to like in Lempicka, there is virtually nothing worth singing about in Tommy.

In his Esquire review, John Simon called Tommy “the most stupid, arrogant, and tasteless movie since Russell’s Mahler. To debate such a film seems impossible: anyone who can find merit in this deluge of noise and nausea has nothing to say to me, nor I to him.” Although I’m not as vitriolic as Simon, I felt similarly about the movie — and now about the current Broadway revival.

The Who’s double album is a masterpiece about a young boy who witnesses a violent death and loses the ability to see, hear, and speak. The record delves into Tommy’s mind as he is abused and harassed by relatives and strangers but finds surprising success at pinball. The loose narrative allows the listener to fill in the blanks by using their imagination.

That imaginative space was taken away by the bizarre film, but the original Broadway musical version from 1993, with music and lyrics by Pete Townshend of the Who and book by Townshend and director Des McAnuff, did an admirable job of bringing the somewhat convoluted tale to the stage, earning ten Tony nominations and winning five trophies, for director, choreographer, score, scenic design, and lighting. With McAnuff again directing, this iteration earned a solitary nod as Best Revival of a Musical, which is one too many.

Mrs. Walker (Alison Luff) tries to help her young son in The Who’s Tommy (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

It’s 1941, and Captain Walker (Adam Jacobs) goes off to war. His pregnant wife (Alison Luff) is devastated when the military arrives at her doorstep and tells her that her husband has been killed in action — even though he is actually in a prison camp. Four years later, Captain Walker returns home to find his wife has taken a new lover (Nathan Lucrezio); the men get into a scrap, and the captain shoots the lover dead. Four-year-old Tommy (Cecilia Ann Popp or Olive Ross-Kline) witnesses the scene, and his parents plead with him, “You didn’t hear it. / You didn’t see it. / You won’t say nothing to no one / Ever in your life.” The boy takes those words to heart.

As he grows up (played by Quinten Kusheba or Reese Levine at ten and Ali Louis Bourzgui as a teenager and adult), he is taken advantage of by his uncle Ernie (John Ambrosino) and cousin Kevin (Bobby Conte) while his mother and father try to cure him by taking him to a psychiatrist (Lily Kren), a specialist (Sheldon Henry), and a prostitute known as the Acid Queen (Christina Sajous). But he shows no interest in life — although he does spend a lot of time looking at himself in a large mirror — until he winds up at a pinball machine, where he proves to be a wizard and soon becomes a hero to millions, the modern-day equivalent of a YouTube gamer going viral. Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean everything is suddenly coming up roses for him.

McAnuff, choreographer Lorin Latarro, set designer David Korins, projection designer Peter Nigrini, costume designer Sarafina Bush, lighting designer Amanda Zieve, and sound designer Gareth Owen bombard the audience with so much nonsense that it is impossible to know what to look at or listen to at any given moment; it’s like the London Blitz has taken over the theater for 130 overcharged minutes (with intermission), complete with dancing uniformed fascists. The orchestrations by Steve Margoshes and Rick Fox are fine, but this has to be about much more than just the Who’s spectacular songs, too many of which tilt here. The barrage of empty frames and projected images might hurt your neck and give you a headache, while the vast amount of unnecessary movement and strange costume choices will have you bewildered, as will the decision to have no actual pinball machines onstage, just a pretend table.

Luff (Waitress, Les Misérables) and Jacobs (Aladdin, Les Misérables) avail themselves well amid the maelstrom, as do the younger Tommys, but Bourzgui, in his Broadway debut, fails to bring any nuance to the character, whether he is patrolling the stage following his younger selves or being chased by Sally Simpson (Haley Gustafson). He’s certainly no Roger Daltrey, on the record or in the film.

This hyperkinetic mess is no sensation, lacking emotional spark as it takes the audience on a less-than-amazing journey for which there appears to be no miracle cure.

Tamara de Lempicka (Eden Espinosa) examines her work in biographical Broadway musical (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

LEMPICKA

Longacre Theatre

220 West 48th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 19, $46-$269

lempickamusical.com

Many of the technical aspects of Lempicka are oddly similar to those of Tommy. Just as Tommy never plays an actual pinball machine, Tamara de Lempicka (Eden Espinosa) never actually paints; she often stands in front of an easel with no canvas, carefully moving a brush in her hand. Riccardo Hernández’s set is laden with empty frames much like those in Tommy. Paloma Young’s costumes for the fascists are overwrought, like Sarafina Bush’s in Tommy.

However, Bradley King’s lighting makes sense, playing off Lempicka’s Art Deco style and angular figuration, while Peter Nigrini’s projections provide necessary historical context and spectacular presentations of her work.

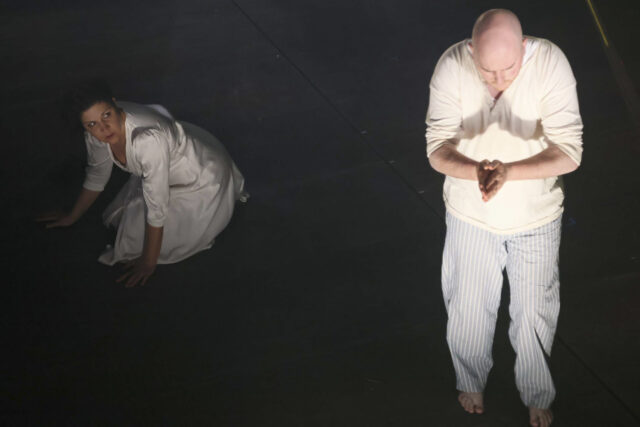

But the biggest difference is in the two leads. Espinosa gives a powerful, yearning performance as Lempicka, a woman caught between her traditional family — husband Tadeusz Lempicki (Andrew Samonsky) and daughter Kizette (Zoe Glick) — and her lover, Rafaela, beautifully portrayed by Amber Iman. (Rafaela is a conglomeration of Lempicka’s girlfriends rather than any one of her individual historical lovers.) She is also trapped by her desire to become an artist and go out clubbing at a time when women were expected to stay home and take care of the household.

The story is bookended by an older Lempicka sitting on a park bench in Los Angeles in 1975 with an easel; at the beginning, she recites a kind of mantra: “plane, lines, form. / plane, color, light.” A moment later, she sings, “Do you know who I am? . . . An old woman who doesn’t give a damn / that history has passed her by / History’s a bitch / but so am I / How did I wind up here?”

In 1916, during WWI, Lempicka marries lawyer Tadeusz, whose prominent family wanted him to wed a woman of higher status. (The book, by Carson Kreitzer and Matt Gould, plays fast and loose with some of the facts for dramatic purposes.) Tadeusz is arrested in the Bolshevik Revolution, and Lempicka goes to extreme lengths with a commandant (George Abud) to get him released. After losing everything, they start all over in Paris, where Tadeusz takes a job at a small bank and Lempicka mops floors. While he is obsessed with finding out what she did to get him freed, she explores her art, experiencing Paris’s nightlife and meeting Rafaela, a prostitute, at a lesbian club run by Suzy Solidor (Natalie Joy Johnson), who later opens the hot La Vie Parisienne.

Lempicka is energized by her new lifestyle, but her husband is growing suspicious — and jealous when, helped by the Baron Raoul Kuffner de Diószegh (Nathaniel Stampley), his wife (Beth Leavel), and Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Abud), Lempicka’s art career starts taking off. “We do not control the world,” Marinetti tells Lempicka. “We control one flat rectangle of canvas.”

When using Kizette as a model, Lempicka can’t differentiate between art and life. Kizette pleads, “mama, look at me / mama, look at me / see me / keeping so still / while your eyes dart back and forth / me / the canvas / me / the canvas / me / me / mama, look at me.” But all Lempicka can offer is, “eyes, Paris blue . . . flecked Viridian green . . . my daughter / shape and volume / color and line.”

Rafaela (Amber Iman) creates a sensation in Lempicka (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

Lempicka garnered well-deserved Tony nominations for Espinosa (Rent, Wicked) for Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role in a Musical, Iman (Soul Doctor, Shuffle Along) for Best Performance by an Actress in a Featured Role in a Musical, and Hernandez and Nigrini for Best Scenic Design of a Musical. In key supporting parts, Johnson (Kinky Boots, Legally Blonde) and Abut (Cornelia Street, The Visit) overdo it, while Glick (Unknown Soldier, The Bedwetter) is sweet as Kizette and Tony winner Leavel (The Drowsy Chaperone, Crazy for You) stands out as the Baroness, but both could use more to do.

Tony-winning director Rachel Chavkin (Hadestown, Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812) has too much going on, unable to get a firm grip on the action, while Raja Feather Kelly’s choreography brings too much attention to itself. Kreitzer’s music, with orchestrations by Cian McCarthy, meanders too much, often feeling out of place as the narrative changes locations and emotional depth, while Gould’s lyrics range from the absurd (“The Beautiful Bracelet,” a love song to a piece of jewelry; “Women,” in which the ensemble declares, “Suzy / You’ve made an Oasis / we live through the days / till we can be Here / Where Everything — and Nothing / is Queer”) to the obvious (“Pari Will Always Be Pari,” “The New Woman”) to the heartfelt (a pair of lovely duets between Espinosa and Samonsky on “Starting Over” and Iman and Samonsky on “What She Sees”).

“I can see the appeal,” Rafaela sings, and it is easy to see the appeal in a show about Tamara de Lempicka. Unfortunately, this one is not it.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]