Iago (Daniel Craig) makes his case to Othello (David Oyelowo) in gripping NYTW production (photo by Chad Batka)

New York Theatre Workshop

79 East Fourth St. between Second & Third Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 18, $129

Thursday, January 12 benefit, $1,500 – $2,500

www.nytw.org

“Were I the Moor I would not be Iago. In following him, I follow but myself. Heaven is my judge, not I for love and duty,” Iago (Daniel Craig) says in the first scene of William Shakespeare’s Othello. “I am not what I am.” What he is is a villain, one of the most devious in the Bard’s canon, and in Sam Gold’s captivating, intense production at New York Theatre Workshop, the audience is also Iago’s judge. Set designer Andrew Lieberman has transformed NYTW into a plywood-encased military barracks where the audience sits on benches on three sides of the action, the main sections holding rows of twelve people, like courtroom juries. The soliloquies are delivered as if closing statements in a trial, the characters trying to convince the audience of their innocence — or guilt. Reminiscent of Nicholas Hytner’s 2013 National Theatre production set in a contemporary military base (among other locations), NYTW’s version is sparer, the long, narrow stage area featuring mattresses and lights on the floor. Iago, ensign to military hero and Moor Othello (David Oyelowo), is determined to exact revenge on Othello for an unproved slight by sabotaging his marriage to Desdemona (Rachel Brosnahan), the daughter of Venetian senator Brabantio (Glenn Fitzgerald). With the help of his naïve friend Roderigo (Matthew Maher), Iago concocts a plan to drive Othello mad with jealousy, trying to convince him that Desdemona is in love with Michael Cassio (Finn Wittrock), Othello’s dedicated captain. “Thou art sure of me. I have told thee often, and I retell thee again and again, I hate the Moor,” Iago says to Roderigo. “My cause is hearted; thine hath no less reason. If thou canst cuckold him, thou dost thyself a pleasure, me a sport,” he adds, explaining how he will get even with Othello, believing that the Moor might have bedded his wife, Emilia (Marsha Stephanie Blake). After Roderigo exits, Iago states his case to the audience-jury: “And it is thought abroad that ’twixt my sheets ’has done my office. I know not if ’t be true, but I, for mere suspicion in that kind, will do as if for surety. He holds me well. The better shall my purpose work on him.” As Othello falls for the ruse, tragedy awaits.

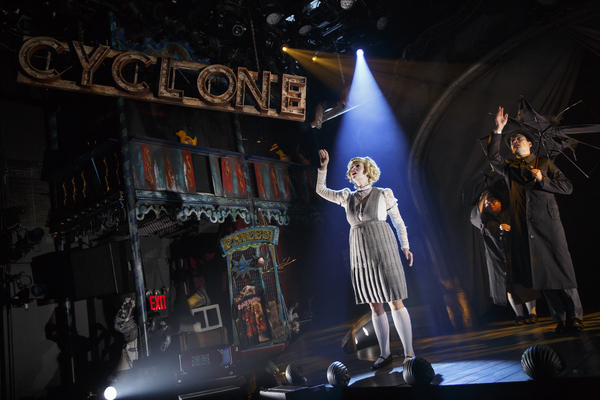

New York Theatre Workshop is transformed into military barracks in Sam Gold’s OTHELLO (photo by Chad Batka)

Royal Shakespeare Company veteran Oyelowo (Volpone, Prometheus Bound) and Craig (A Steady Rain, Casino Royale) make a formidable duo as Othello and Iago, roles previously played by such pairs as Paul Robeson and José Ferrer, Richard Burton and John Neville (alternating parts), Laurence Olivier and Frank Finlay, Chiwetel Ejiofor and Ewan McGregor, and Laurence Fishburne and Kenneth Branagh. Craig is tough and determined as Iago, dead-set on succeeding in his evil goal, while Oyelowo combines an engaging ardor with a heartbreaking vulnerability. Emmy nominee Brosnahan (The Big Knife, House of Cards) plays Desdemona with a strong independence, Blake (Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Hurt Village) brings depth to Emilia, and Wittrock (Death of a Salesman, American Horror Story) is firm and solid as the loyal Cassio. Through much of the play, other soldiers (Blake DeLong, Anthony Michael Lopez, Kyle Vincent Terry, Slate Holmgren) roam the stage, carrying machine guns, as if violence can explode at any moment, always on the verge of war, keeping things tense as well as frighteningly contemporary, given the state of the world today. Tony winner Gold (Fun Home, The Flick) keeps the racial aspect of Othello simmering just below the surface, ever-present but not overwhelming, casting a black Othello and Emilia and a white Iago and Desdemona among the multiracial cast. (Surprisingly, for most of the twentieth century, Othello was played by white men in major productions, sometimes in blackface.) Gold occasionally breaks the tension with drinking songs led by DeLong on guitar, the characters declaring at one point, “We are, we are, we are, we are the Engineers. / We can, we can, we can demolish forty beers. / Drink up, drink up, drink up and come along with us / ’Cause we don’t give a damn about any old man who don’t give a damn about us.” They’re odd but necessary sidebars in this powerful and intimate three-hour show that grabs you and never lets you go.