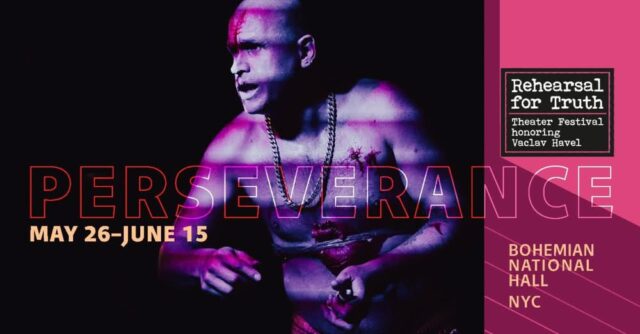

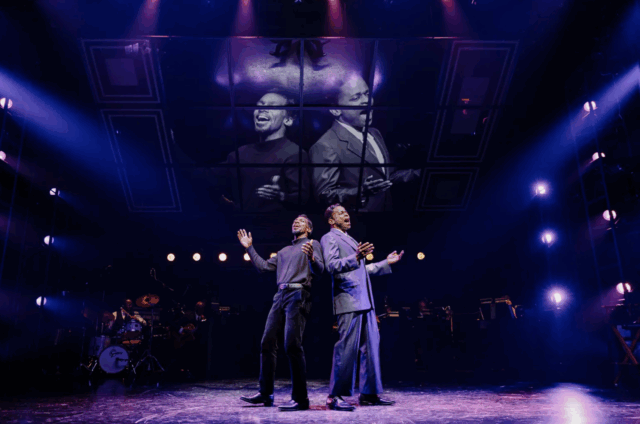

Sammy Davis Jr. (Daniel J. Watts) and Nat King Cole (Dulé Hill) form a unique partnership in Lights Out (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

LIGHTS OUT: NAT “KING” COLE

New York Theatre Workshop

79 East Fourth St. between Second & Third Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 29, $49-$59

www.nytw.org

According to the Sleep Foundation, a fever dream can be “vivid and unpleasant,” involving feelings of “discomfort” that can be “unsettling.”

That’s precisely how I felt while watching the bio-jukebox musical Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole at New York Theatre Workshop.

“How is everybody doing tonight? Fine and dandy? Wonderful. Some of you thought you were going to get a nice and easy holiday show. No! Welcome to the fever dream,” Sammy Davis Jr. (Tony nominee Daniel J. Watts) tells the audience at one point. “My dear friend is wrapped up at the moment. Wrapped up in his mind. The mind is a terrible thing. Is that the way the saying goes? Anyway. When my friend is wrapped up, he does what any musician will do. He will try to work it out. Work it out in a song.”

Lights Out takes place on December 17, 1957, at NBC studios in New York City, as Cole (Emmy nominee Dulé Hill), the friend Davis is referring to, is preparing for the final episode of his television variety program. Despite its critical and popular success, the year-old show could not garner a single national sponsor, primarily because it was being hosted by a Black man. “Madison Avenue is afraid of the dark,” Cole famously announced to the press.

Candy (Kathy Fitzgerald), the makeup designer, enters Cole’s dressing room, ready to apply the usual white powder that will make him look less Black, but he asks for a lighter touch this time; he’s determined to go out with his “head held high.” He walks onstage and is upset that someone has left the ghost light on, a sign of bad luck; according to theater superstition, it should only be on when the theater is empty overnight, for the spirits wandering around. As soon as he turns the light off, the narrative switches over to the fever dream, where anything can happen, from traveling into the past to speaking one’s innermost thoughts like never before.

Serving as the emcee of the dream is Davis, one of Cole’s closest friends, but in this case he is a devilish trickster, manipulating some of the action and regularly addressing the audience directly, advising Cole that they will be “taking it off the rails.” What follows is a haphazard mess of a story interspersed with classic Cole tunes from his remarkable songbook, which boasts eighty-six singles and seventeen albums in the top 40 between 1943 and 1964 and total sales of more than fifty million records.

Cole assures the stage manager (Elliott Mattox) that Peggy Lee (Ruby Lewis), who is late, will make it in time to perform the opener with him. When he gets too close to Betty Hutton (Lewis) during “Anything You Can Do,” a “Racial distance appropriateness” yardstick is thrust between them. Eartha Kitt (Krystal Joy Brown) purrs to the producer and stage manager, “Piss off!” after they tell Cole to “keep it clean.” Cole tells the eleven-year-old piano prodigy Billy Preston (Mekhi Richardson or Walter Russell III) that he could become president one day, although the cue cards use racist tropes involving sports and prison. The Randy Van Horne Singers join Cole for “It’s a Good Day,” which features the line “It’s a good day for shining your shoes / And it’s a good day for losin’ the blues,” as if Cole’s Blackness is being whitewashed.

These set pieces all pass through in a chaotic, confusing jumble, with Davis continually interrupting with an annoying demeanor. The most effective scene occurs when Cole’s long-deceased mother, Perlina (Kenita Miller), arrives to deliver love and support, singing “Orange Colored Sky” and reminding her son (played as a child by Richardson or Russell III), “Don’t let ’em get the best of you. Keep your head held high.” Another highlight is Cole and Davis tap-dancing to “Me and My Shadow” right after Cole fires his producer (Christopher Ryan Grant). “You can’t fire me. You don’t wield that kind of power!” the producer argues. Cole responds, “I absolutely-positively wield that kind of power.” Cole then kicks him out when the producer declares, “How dare you, after all I’ve done for you people.”

Cole took some heat from the Black community for not being more aggressive in fighting racism, and Lights Out posits that while he was well aware of that criticism, he opted to take a different path, by being successful and paving the way for other Black entertainers, on television and Madison Ave. During one fake commercial, Sammy and Perlina promote toothpaste, referencing the racist caricature of smiling Blacks. Sammy: “When you’re feeling down / And all you want to do is frown / Use this tube of magic / To avoid a life that’s tragic / Brush up and smile bright / Some things ain’t worth the fight.” Perlina: “I know deep down that you’re right.” Perlina and Sammy: “Next time I will try to smile bright.” Other ads are for beer and cigarettes.

Emmy nominee Dulé Hill star as Nat “King” Cole in biomusical at New York Theatre Workshop (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

Lights Out was written by Tony and Oscar nominee Colman Domingo and Patricia McGregor with a nonstop ferocity, trying to squeeze too much into ninety minutes. McGregor (Hamlet, Hurt Village) directs at a feverish pace, making it hard for the audience to catch its breath as they attempt to figure out what is going on. Clint Ramos’s TV show set is effective, with Cole’s dressing room stage right and the band in the back, but the inclusion of an angled video screen for live projections by David Bengali feels unnecessary, further hampering the abstract narrative. Katie O’Neill’s costumes range from practical to lavish, with Cole always looking superbly elegant and pristine.

The orchestrations and arrangements by John McDaniel are lovely, evoking the time period while paying respect to composer and bandleader Nelson Riddle, although some songs are performed only in part and, curiously, the producer warbles “Mona Lisa.” Edgar Godineaux’s choreography has a keen sense of humor, while Jared Grimes’s tap choreography shines.

Like most biomusicals, the script plays hard and loose with some of the facts. While Cole’s final show was on December 17, 1957, the actual guests were the Cheerleaders and Billy Eckstine, and the opening song was “When You’re Smiling.” Davis, Hutton, Kitt, and Lee all appeared on one episode of the show, but not the last one. In addition, Davis makes a joke referencing the slogan of the United Negro College Fund, “A mind is a terrible thing to waste,” but that began in 1972, seven years after Cole died; even though Davis is an otherworldly figure in the dream, everything else relates to 1957.

Hill (After Midnight, Stick Fly) beautifully captures the dichotomy tearing Cole apart inside, but Watts (Richard III, Tina: The Tina Turner Musical) overplays Davis to the point of cutting down the impact of many scenes.

The story of Nat “King” Cole, who died of lung cancer in 1965 at the age of forty-five — there is a whole lot of smoking in the show — is a crucially important one. In February 1958, Cole wrote in Ebony magazine, “For 13 months I was the Jackie Robinson of television. I was the pioneer, the test case, the Negro first. I didn’t plan it that way, but it was obvious to anyone with eyes to see that I was the only Negro on network television with his own show. On my show rode the hopes and tears and dreams of millions of people. . . . Once a week for 54 consecutive weeks I went to bat for these people. I sacrificed and drove myself. I plowed part of my salary back into the show. I turned down $500,000 in dates in order to be on the scene. I did everything I could to make the show a success. And what happened? After a trailblazing year that shattered all the old bugaboos about Negroes on TV, I found myself standing there with the bat on my shoulder. The men who dictate what Americans see and hear didn’t want to play ball.”

At one point, Cole’s daughter Natalie (Brown) duets with her father, singing “Unforgettable.” It’s a touching moment, but it’s a shame that too much of the rest of the show is forgettable.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]