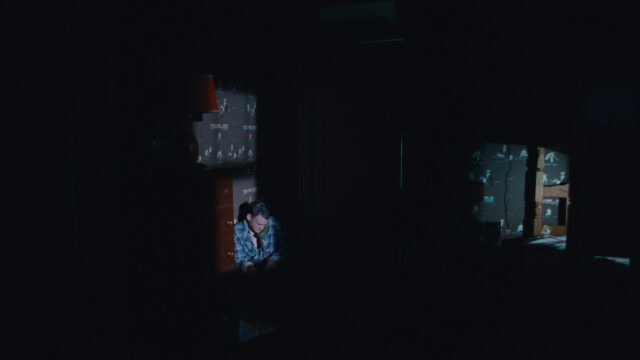

Giancarlo Esposito plays a philosophical cabbie in Julian Rosefeldt’s Euphoria (photo by Nicholas Knight / courtesy of Park Avenue Armory)

EUPHORIA

Park Ave. Armory, Wade Thompson Drill Hall

643 Park Ave. at Sixty-Seventh St.

Daily through January 8, $18

www.armoryonpark.org

“The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed — for lack of a better word — is good,” Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) famously pronounced in Oliver Stone’s Oscar-nominated 1987 film, Wall Street. “Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms — greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge — has marked the upward surge of mankind. And greed — you mark my words — will not only save Teldar Paper but that other malfunctioning corporation called the USA.”

Well, as it turns out, greed has not exactly saved America or the world, but is there still hope? German filmmaker Julian Rosefeldt explores that possibility in his beautifully rendered twenty-four-channel immersive installation, Euphoria, continuing at Park Avenue Armory through January 8. It arrives at an opportune moment, not only in the midst of a post-global-pandemic economic crisis but during the holiday season, when rampant consumerism dominates our everyday life.

In 2016, Rosefeldt presented Manifesto at the armory, a thirteen-channel film projected on screens placed throughout Wade Thompson Drill Hall, featuring Cate Blanchett as twelve different characters spouting cultural missives by artists and philosophers going back more than 150 years. One of the themes came from Jim Jarmusch: “Nothing is original.” While nearly all the dialogue in Euphoria is taken from another source, how it is incorporated into a 115-minute visual and aural feast is anything but derivative or uninventive. And it’s about a lot more than just the Benjamins.

Euphoria comprises six distinct scenes, each of which exists on its own in a loop; you can enter at any time, as the order doesn’t matter. The linking factor is the discussion of socioeconomics in the modern world. There are black fold floor chairs scattered around the space, but you can also walk around the installation. The main screen hangs at the center, where the six stories are told. Five smaller screens are at the same level in a circle, where drummers Terri Lyne Carrington, Peter Erskine, Yissy García, Eric Harland, and Antonio Sanchez occasionally pick up their sticks and play. Eighteen more screens surround the space, except for the entrance, on which 140 members of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus are projected, life-size; in the dark hall, it often looks like they are actually there, in person, singing or, when silent, standing more or less still, their slight swaying adding a dash of reality to the primary narrative, which delves into the fantastical. (The score is by Samy Moussa, with an additional composition by Cassie Kinoshi.)

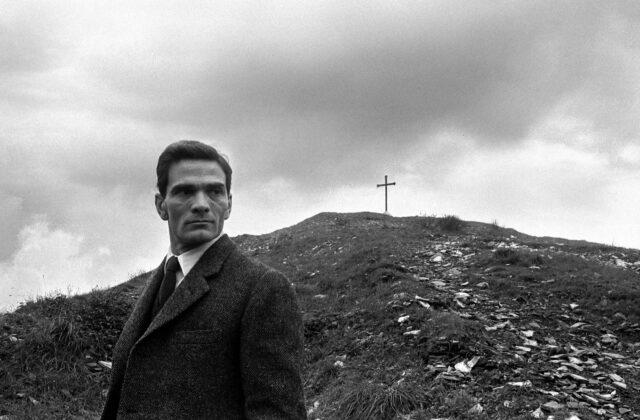

Julian Rosefeldt’s twenty-four-channel installation surrounds viewers (photo by Nicholas Knight / courtesy of Park Avenue Armory)

On a cold winter night in New York City, a taxi driver played by Giancarlo Esposito, partially channeling his character from Jarmusch’s Night on Earth, including his “fresh” winter hat with earflaps, picks up a well-dressed man with shopping bags who is going to the Brooklyn Navy Yard; it’s not long before we realize Esposito is playing both roles. The cabbie does most of the talking, his dialogue made up of quotes from John Steinbeck, Noam Chomsky, Fareed Zakaria, G. K. Chesterton, JR, Milton Friedman, Ayn Rand, and others, seamlessly woven together. “My momma always said: Too many people buy things they don’t need with money they don’t have to impress people who don’t care,” the cabbie says (Will Rogers). Passing by strange things happening on the street, the cabbie delivers lines that essentially sum up much of what Euphoria is about: “And then they see their idealism turn into realism, their realism into cynicism, their cynicism turn into apathy, their apathy into selfishness, their selfishness into greed and then they have babies, and they have hopes but they also have fears, so they create nests that become bunkers, they make their houses baby-safe and they buy baby car seats and organic apple juice and hire multilingual nannies and pay tuition to private schools out of love but also out of fear. What happened? You start by trying to create a new world and then you find yourself just wanting to add a bottle to your cellar, you see yourself aging and wonder if you’ve put enough away for that and suddenly you realize that you’re frightened of the years ahead of you. You never think you’ll become corrupt but time corrupts you, wears you down, wears you out. You get tired, you get old, you give up on your dreams. . . . You mind who you think you wanted to be” (Don Winslow).

The action moves next to a postapocalyptic ship graveyard where five white homeless men, Poet, Smartass, Randy, Keynes, and Sidekick, gather around a trash fire, discussing the “three great forces [that] rule the world: stupidity, fear, and greed” (Albert Einstein). Randy declares, “It seems to me that not doing what we love in the name of greed is just very poor management of our lives. I will tell you the secret to getting rich: Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful!” (Warren Buffett). Quotes from Machiavelli, Snoop Dog, Erich Fromm, Socrates, Adam Smith, Stephen King, Elizabeth Warren, and more are interwoven as the men pass around a bottle of rum, eat marshmallows, and burn a smartphone and, unbeknownst to them, a parade of animals in the background boards a large wooden ship, as if a new world is starting that the men will not be part of.

In a parcel delivery factory, three women (Virginia Newcomb, Ayesha Jordan, Kate Strong) work an assembly line, scanning and organizing packages while discussing how “things can only get worse” (Invisible Committee). They detail their struggles with overwhelming debt, long hours and low pay, racial injustice, motherhood, and misogyny and sexualization, sharing the words of Audre Lorde, Sojourner Truth, Ursula K. Le Guin, Angela Davis, bell hooks, Cardi B, and Frantz Fanon. “You sound like an archaeologist!” one of the women says to her conveyor-belt mate, who responds, “That’s right! I am an archaeologist. You wanna know why? ’Cause my life lies in fucking ruins.”

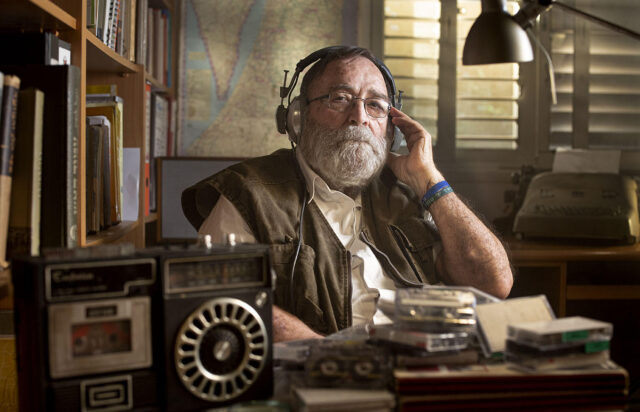

One of the scenes in Euphoria takes place in a surreal bank (photo by Nicholas Knight © Julian Rosefeldt / courtesy of Park Avenue Armory)

An elegant Kyiv bank turns into a surreal carnival in a scene that kicks off with a doorman (Yuriy Shepak) looking into the camera and saying, “It is a kind of spiritual snobbery that makes people think they can be happy without money” (Albert Camus). A moment later he adds, “Money is like blood. It gives life if it flows. Money enlightens those who use it to open the flower of the world” (Alejandro Jodorowsky). Excerpts from Yuval Noah Harari, Michael Lewis, Matt Taibbi, Bertolt Brecht, George Carlin, Don DeLillo, and Karl Marx merge as a security guard (Nina Songa), a mother (Evgenia Muts), a homeless woman (Elena Aleksandrovich), and a cleaner (Corey Scott-Gilbert) go about their business, the bankers transforming into magicians, acrobats, and dancers. It’s a Busby Berkeley celebration in which money isn’t real, just another trick or performance. As the cleaner notes, “Money isn’t a material reality — it is a psychological construct. It works by converting matter into mind. So why does it succeed? Because people trust the figments of their collective imagination. Trust is the raw material from which all types of money are minted. Religion asks us to believe in something. Money only asks us to believe that other people believe in something” (Yuval Noah Harari).

In another vignette, six skate teens (Rocio Rodriguez-Inniss, Esther Odumade, Tia Murrell, Dora Zygouri, Asa Ali, and Luis Rosefeldt) come together in an abandoned bus terminal talk to about the future, debating quantitative vs. qualitative value, spouting lines from Arthur C. Clarke, Victor Hugo, William Shakespeare, Aldous Huxley, and John Maynard Keynes. “It’s considered sexy to accumulate property, money, stocks, cars. What a waste of dopamine and adrenaline if it’s all just about quantity, right?” (JR) one of the girls asks. “Right,” replies a second girl. “I mean, if a monkey hoarded more bananas than it could eat, while most of the other monkeys starved, scientists would study that monkey to figure out what the heck was wrong with it. When humans do it, we put them on the cover of Forbes” (Nathalie Robin Justice). One of the boys points out, “A brutal state of affairs, profoundly inegalitarian, is presented to us as ideal” (Alain Badiou), adding, “We humans want to compete with each other, to grow, to invent, to expand. Fair enough. But why not within an ethically defined framework, based on common shared values” (JR). As almost always, the younger generation believes they can change the world for the better, through education and the reestablishment of goals based on equality and what’s best for all, not competition that serves the few. “We need to think big. Our natural habitat has always been the future, and this terrain must be reclaimed” (Nick Srnicek/Alex Williams) a third girl says. But as a fourth girl points out, “No wonder the galaxies recede from us in every direction, at the speed of light. They are frightened. We humans are the terror of the universe” (Edward Abbey). Perhaps unsurprisingly, this section contains the most original dialogue, as the teenagers seek to discover what comes next for themselves and not just relying on existing theories.

My cycle concluded in a large supermarket, where a bold, beautiful, ever-threatening tiger (voiced by Blanchett) makes its way up and down the aisles of canned, boxed, and bottled food and drink. It warns us, “Of the world as it exists, it is not possible to be enough afraid (Theodor W. Adorno). History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce (Karl Marx). Those who do not know history are condemned to repeat it. But even knowing can’t save them. ’Cause what is constant in history is greed and foolishness and a love of blood (Cormac McCarthy).” With quotes from Thomas Hobbes, Terry Pratchett, A. S. Byatt, Marquis de Sade, and Theodor W. Adorno, the hungry, swaggering animal accuses humans of being short-sighted power-mongers, filled with hatred and violence, whose extinction would bring no harm to the planet; in fact it would be welcomed. But the tiger adds, “And the best at war, finally, are those who preach peace. Beware the preachers. Beware the knowers. Beware their love” (Charles Bukowski).

In his 2000 breakthrough hit, “Ride wit Me,” Nelly proclaimed, “Hey, must be the money!” In Euphoria, Rosefeldt zeroes in specifically on greed and its devastating cost on humanity. At the beginning of the bank scene, the doorman says, “For thousands of years, philosophers, thinkers, and prophets have besmirched money and called it the root of all evil,” quoting Hurari. But the full biblical quote from the apostle Paul in Timothy 6:10 actually puts it in a different perspective: “For the love of money is the root of all evil: which while some coveted after, they have erred from the faith, and pierced themselves through with many sorrows.” Today, more than ever, with more of the planet’s wealth in very few hands, financial institutions are like houses of worship, evoked further by the celestial sounds of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus in the armory. Perhaps the security guard says it best when, quoting one of the wisest sages of the last fifty years, George Carlin, he says, “Give a man a gun and he can rob a bank. Give a man a bank and he can rob the world.”