Writer, director, choreographer, and performer Amanda Szeglowski dreams of fame and fortune in Stairway to Stardom (photo by Maria Baranova)

STAIRWAY TO STARDOM

HERE

145 Sixth Ave. at Dominick St.

September 12-23, $18-$45, 8:30

212-647-0202

www.here.org

Before there was Star Search, American Idol, The Voice, and America’s Got Talent there was Stairway to Stardom, a no-budget New York City public access television show in which men, women, and children performed with big dreams in their heads, hoping to make it big. Writer, director, choreographer, performer, and “global paradigm architect” Amanda Szeglowski explores the American dream of reaching for fame and fortune in the vastly entertaining and ridiculously clever multimedia production Stairway to Stardom, which opened at HERE on September 12. The sixty-minute show features Szeglowski and her cakeface company, Ali Castro, Jade Daugherty, Ayesha Jordan, and Nola Sporn Smith, in glittery silver-sequined gowns and high heels singing, dancing, and sharing their successes and failures, their hopes and desires with a dry, wry mechanical delivery deliciously at odds with the spectacular longing for stardom that lies beneath.

The narrative follows the arc of a contemporary U.S. life in the arts, from what creative kids want to be when they grow up and what their parents expect of them to discovering their unique talent and then working odd jobs as they strive for artistic (and maybe even financial) success while also experiencing regrets. The performers are joined by Prism House — Brian Wenner and Matt O’Hare — who provide live video and music mixing, featuring excerpts from the original public access program. Szeglowski, who is also HERE’s marketing director, formed the all-female cakeface in 2008; their previous “linguistic performance art” projects include Don’t Call Me McNeill., Alpha Pups, and Harold, I Hate You. The new show continues through September 23; there will be a talkback following the September 20 performance, and September 15 and 19 are ’80s nights, in which the audience is encouraged to dress with their best retro flair. The show begins at 8:30, but HERE will be projecting clips from the original Stairway to Stardom in the lounge beginning at 7:00 every evening. Shortly after opening night, which kicked off HERE’s twenty-fifth anniversary season, Szeglowski found time to answer some questions about her own career trajectory.

twi-ny: As you were preparing for the opening of Stairway to Stardom, your native Florida — you went to high school in Tampa and college at USF — was being battered by Hurricane Irma. What was that experience like, balancing the two? Are your friends and family safe?

amanda szeglowski: Yes, thank you for asking. My family lives in West Tampa, so we were all watching the storm very closely. It was an incredibly stressful time to be in tech rehearsals all day and night approaching the culmination of a show I’ve been building for three years while this monster of a storm was creeping towards my family. I was checking in on them every chance I got and FaceTiming to see all the prep they were doing to their houses, going over the evacuation plans. . . . Being a part of that process helped me feel like I was with them. But growing up in Florida and having been through many hurricanes actually gave me some comfort as well. We know how to prepare and we take it seriously. That’s not to say that wine isn’t the first thing in the hurricane supply shopping cart — it is. But I felt better knowing this wasn’t my family’s first rodeo; they knew exactly what to do.

Nola Sporn Smith, Jade Daugherty, Ayesha Jordan, Amanda Szeglowski, and Ali Castro reach for the stars in glittering show at HERE (photo by Maria Baranova)

twi-ny: Were you ever a fan of such programs as Star Search, American Idol, The Voice, or America’s Got Talent?

as: I loved watching Star Search as a kid. As I got older and the shows got more scripted I lost interest. I think Idol changed the game by making the auditions part of the show, and then it became a gimmick of who could be the most outrageous. But I will occasionally watch clips from these shows when my parents call me and insist that they just saw the greatest thing.

twi-ny: What is it about the public access show that spurred your creative juices? You treat it with respect without getting overly kitschy or mean-spirited.

as: The TV show was so raw — so vulnerable. These weren’t people trying to become a character on a reality show; these were people really trying to make it. I respect that. There wasn’t any competitive aspect to the TV show; they were just performing and hoping to be seen. Sure, when you see clips from the TV show there are moments that you want to laugh, but I spent hours and hours interviewing people about their lives for my script, and a lot of it was pretty damn sad. At least these people were out there trying. I wanted to honor that drive and explore what happens to all of us along the way, because I think that fire is there for almost everyone in the beginning.

twi-ny: What kind of talent does someone have to display to become a member of cakeface? When someone is auditioning for you, are you more like Simon Cowell, Paula Abdul, Jennifer Lopez, Usher, or Miley Cyrus?

as: HAHAHA. I think I’m a Simon and Paula hybrid. I’m Simon because I have a crystal-clear vision of what I want, and if you don’t fit, I am not going to beat around the bush. I never want to waste anyone’s time. But Paula has a way of finding a spark in people and being respectful of their contributions, and I try to always do that. I’ve received many post-audition emails over the years from people that I didn’t hire saying the experience was really special. I’m proud of that.

twi-ny: Is anyone associated with the public access show still around? Did you have to go through any kind of permissions process to use some of the original footage?

as: The show was public access. But I did get the tapes directly from someone who was given them by the host of the show, Frank Masi, before he died. [Ed. note: Masi passed away in 2013 at the age of eighty-seven; you can watch a YouTube tribute to him and the show here.]

Amanda Szeglowski takes a well-deserved break from climbing the stairs to stardom (photo courtesy of Amanda Szeglowski)

twi-ny: How amazing was it to perform in such great costumes, as well as high heels?

as: The costumes, which are by Oana Botez, are absolutely fantastic. It’s such a blast being able to sparkle head to toe on a downtown stage — very atypical for the scene. The heels are challenging, but anything else with those costumes would be absurd, right? And the performers are all pros, so they make it work. I wanted an over-the-top glamorous look that I could juxtapose with the stark reality of our words. Oana definitely achieved that.

twi-ny: What did you want to be when you were growing up?

as: The opening text, which I call a monologue (even though it’s delivered by five voices), is basically a run-on sentence ticking off all of my childhood dreams. It includes a mermaid, grocery store checkout clerk, princess, trapeze artist, restaurateur, and movie star. Of course, I always wanted to be a dancer, but that’s obvious, and our unfulfilled dreams are so much more interesting.

twi-ny: What’s the worst job you’ve ever had?

as: I’ve had a slew of them. The story in the show about working in the housewares department at Burdines was my life at age fifteen. I had no idea how to sell kitchen appliances and would literally walk away from customers and kick back in the stock room. That was pretty awful. There’s another story about a boss with revolting coffee breath; that was my first job in NYC. But another horrific experience was telemarketing. In high school I worked at a call center selling satellite broadcasting to elderly people in rural areas. I had to convince them they needed HBO. It was super sleazy, plus I got sexually harassed by my boss. I’d say fifteen was not a banner year for my career trajectory.

twi-ny: What would you like audiences to take away from the show?

as: I’d like them to be reminded of our often-naive notions of success and talent, reflect on the choices they’ve made, and leave with a glimmer of hope.

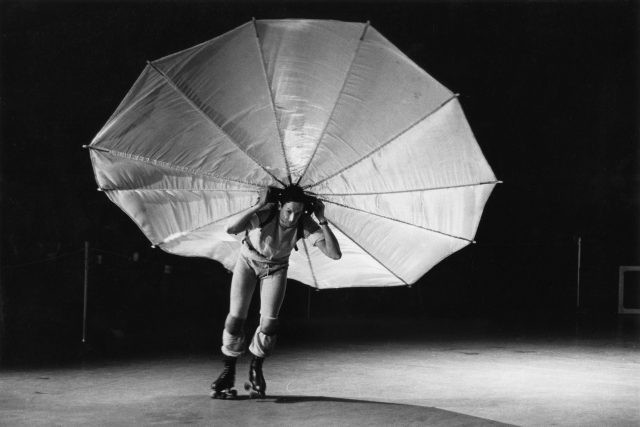

If you didn’t know any better, you might think that Elvia Lund’s extraordinary Bobbi Jene was a fiction film. Danish director and cinematographer Lund, editor Adam Nielsen, and composer Uno Helmersson have employed narrative story techniques in crafting a bold and intimate tale about fear and desire, romance and ambition. But Bobbi Jene is actually a deeply personal documentary about a woman turning thirty and taking stock of her life. “I want to get to that place where I have no strength to hide anything,” Iowa native Bobbi Jene Smith says, and that is evident from the brief opening scene of Bobbi dancing naked and alone. When she was twenty-one, Bobbi moved to Israel to become a member of the world-renowned Batsheva Dance Company, led by choreographer Ohad Naharin, developer of the unique Gaga movement language. (I’ve seen her dance several times with Batsheva and have been touched and impressed by her abilities.) Now that she’s nearly thirty, Bobbi has decided to go back to America and create pieces herself, which she tells Naharin, with whom she had a relationship. “I love being in the company. I love dancing for you,” she says during their talk at a busy café. “I just feel it’s time for me to go make my own work.” Naharin carefully responds, “So it’s painful, but it’s probably also what you need.” Bobbi is not only leaving the troupe but her boyfriend, twenty-year-old company dancer Or Schraiber, who loves her but does not want to leave Tel Aviv. We see her struggling with her decision, trying to convince herself that she can both make a career in the States while also maintaining a long-distance relationship with Or. Once back in America, Bobbi concentrates on her durational solo piece A Study on Effort, a raw, intense work that combines power with vulnerability as she explores pleasure and pain. As she prepares to perform the piece at the Israeli Museum in Jerusalem, all the different parts of her life threaten to overwhelm her.

If you didn’t know any better, you might think that Elvia Lund’s extraordinary Bobbi Jene was a fiction film. Danish director and cinematographer Lund, editor Adam Nielsen, and composer Uno Helmersson have employed narrative story techniques in crafting a bold and intimate tale about fear and desire, romance and ambition. But Bobbi Jene is actually a deeply personal documentary about a woman turning thirty and taking stock of her life. “I want to get to that place where I have no strength to hide anything,” Iowa native Bobbi Jene Smith says, and that is evident from the brief opening scene of Bobbi dancing naked and alone. When she was twenty-one, Bobbi moved to Israel to become a member of the world-renowned Batsheva Dance Company, led by choreographer Ohad Naharin, developer of the unique Gaga movement language. (I’ve seen her dance several times with Batsheva and have been touched and impressed by her abilities.) Now that she’s nearly thirty, Bobbi has decided to go back to America and create pieces herself, which she tells Naharin, with whom she had a relationship. “I love being in the company. I love dancing for you,” she says during their talk at a busy café. “I just feel it’s time for me to go make my own work.” Naharin carefully responds, “So it’s painful, but it’s probably also what you need.” Bobbi is not only leaving the troupe but her boyfriend, twenty-year-old company dancer Or Schraiber, who loves her but does not want to leave Tel Aviv. We see her struggling with her decision, trying to convince herself that she can both make a career in the States while also maintaining a long-distance relationship with Or. Once back in America, Bobbi concentrates on her durational solo piece A Study on Effort, a raw, intense work that combines power with vulnerability as she explores pleasure and pain. As she prepares to perform the piece at the Israeli Museum in Jerusalem, all the different parts of her life threaten to overwhelm her.