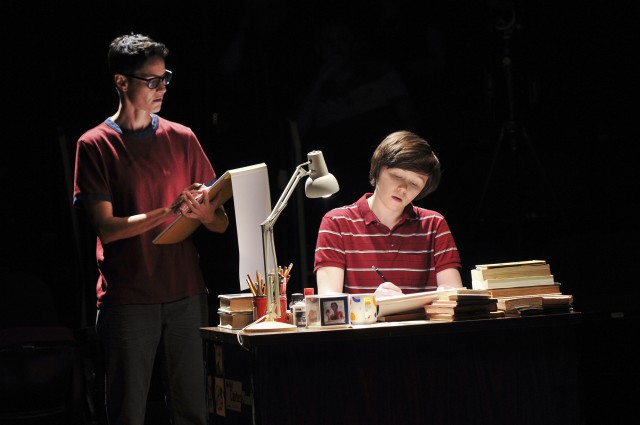

Robert Samson (Jerry O’Connell), Raquel De Angelis (Renée Fleming), Vito De Angelis (Douglas Sills), and Iris Peabody (Anna Chlumsky) get caught up in some crazy shenanigans in LIVING ON LOVE (photo by Joan Marcus)

Longacre Theatre

220 West 48th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 3, $25-$145

www.livingonlovebroadway.com

Opera diva Renée Fleming makes her Broadway debut playing opera diva Raquel De Angelis in Joe DiPietro’s underwhelming, over-the-top romantic farce Living on Love. Based on Garson Kanin’s last play, Peccadillo, Living on Love is set in 1957 in the elegant Manhattan living room of the Diva and her husband, Vito De Angelis (Douglas Sills), a conductor who insists on being called the Maestro. The Diva is a fading star jealous of Maria Callas’s success, while the Maestro never wants to hear anyone mention the name of his archrival, Leonard Bernstein. Robert Samson (Jerry O’Connell) is the latest in a succession of ghost writers — which the Italian Maestro calls “spooky helpers” in his broken English — attempting to work with De Angelis on his memoirs. One afternoon Iris Peabody (Anna Chlumsky) shows up, a mousey editor who is there to either make sure the manuscript is finished or take back the large advance of $50,000 — which the Diva has already spent. Desperate for the money, and suspicious of each other’s motives, soon the Diva is writing her own autobiography with Robert, a huge fan of hers, while Iris is doing the same with the Maestro, who, naturally, loves the ladies. Plenty of high jinks ensue, but you won’t be calling out “Bravo! Brava!”

Living on Love is a tepid tale of music and jealousy, with stale jokes and clichéd situations that the audience can see coming from as far as La Scala. Sills (The Scarlet Pimpernel, Little Shop of Horrors) is excellent as the wild, unpredictable Lothario, chewing up and spitting out Derek McLane’s lovely scenery with a furious panache. Unfortunately, Met Opera star Fleming, O’Connell (Seminar, Stand by Me), and Chlumsky (You Can’t Take It with You, Unconditional) can’t keep up with him, their characters flat and obvious. Blake Hammond and Scott Robertson provide some comic relief — yes, you know you have a problem when a comedy needs comic relief — as the family servants, cleaning up and making minor set changes with aplomb, but their shtick, which also includes singing, grows repetitive fast and, as the latter repeats over and over, “There’s nothing you can do about it.” Tony winner DiPietro (Memphis, Nice Work If You Can Get It) doesn’t give director Kathleen Marshall (Nice Work, Wonderful Town) much of a chance with the musty material. The only saving grace is Sills’s performance, but it’s not enough to salvage the proceedings. Fleming displays occasional flare in her Broadway debut, but her snippets of songs are more of a tease than a treat. You’ll be looking for the fat lady to sing long before the silly finale.