Charles (Tim Pigott-Smith) wonders just who he is now that his mother is dead and he is king (photo by Joan Marcus)

Music Box Theatre

239 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 31, $37 – $159

www.kingcharlesiiibroadway.com

In the 2006 film The Queen, writer Peter Morgan and director Stephen Frears imagine what went on behind closed doors as Queen Elizabeth II (an Oscar-winning Helen Mirren) and Prime Minister Tony Blair (Michael Sheen) debate how to publicly handle the tragic death of Princess Diana. In the 2015 Broadway drama The Audience, writer Morgan and director Stephen Daldry re-create private weekly meetings Queen Elizabeth II (a Tony-winning Mirren) has had with prime ministers going back to Winston Churchill, imagining what they talked about in the sitting room. Both of those productions looked back at the past; in the Olivier Award-winning drama King Charles III, writer Mike Bartlett and director Rupert Goold delve into the near future, imagining an England in which the queen has just died and her son, Prince Charles (Tim Pigott-Smith), finally ascends to the throne. “I never thought I’d see her pass away,” Kate Middleton (Lydia Wilson) says, to which Charles drolly replies, “I felt the same.” Charles almost immediately flouts tradition when, at his first weekly audience with Prime Minister Tristram Evans (Adam James), he refuses to merely listen to what Evans has to say but instead decides to use his royal authority to seriously question the efficacy of a bill that would severely limit freedom of the press. Evans is especially upset at Charles’s response given what happened to Princess Diana. “I would have thought of all the victims you’d feel the strongest something must be done,” Evans boldly declares. “As a man, a father, husband, yes I do. But that’s not who we are when sat with you,” Charles answers. “In here, not just am I defender of the faith but in addition I protect this country’s unique force and way of life.” Charles also chooses to meet with opposition leader Mark Stevens (Anthony Calf) on a weekly basis as well, causing the two men to cross the aisle and strategize together, since every bill must be signed by the king in order to become the law of the land, and Charles is opting to use this ceremonial right to keep the monarchy relevant. Meanwhile, the wild Prince Harry (Richard Goulding) has fallen for Jess (Tafline Steen), a young radical he met at a nightclub. It all makes Charles’s longtime press secretary, the rather stoic and old-fashioned James Reiss (Miles Richardson), more than a bit frustrated. “What am I?” Charles wonders now that he is king.

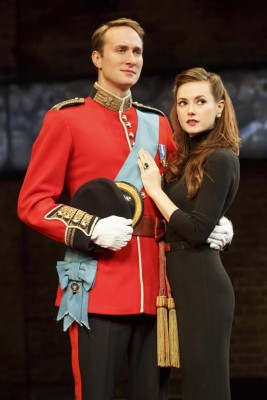

Prince William (Oliver Chris) and Kate (Lydia Wilson) look at a future without Queen Elizabeth in royal Broadway drama (photo by Joan Marcus)

King Charles III arrived at the Music Box Theatre from across the pond with much fanfare (befitting royalty), but it turns out to be rather dry and ordinary, with a stiff upper lip that often gets in the way. As a tribute to old-time England, much of the dialogue is recited in blank verse, with Charles occasionally delivering brief soliloquies to the audience, but the Shakespearean elements (there are ghosts as well, among references to Macbeth and Hamlet) feel out of place, even on Tom Scutt’s medieval-style set, a castle room circled by fading portraits of previous kings. Perhaps part of the problem is that we are too familiar with the characters involved, which also include Camilla Parker Bowles (Margot Leicester); none of the actors completely capture who they are portraying, and the story is overly simplistic, particularly in its depiction of Charles’s sons, who have been real-life tabloid fodder since birth. Bartlett (Cock, Bull) and Goold (American Psycho, Macbeth) keep things too direct, not letting their imaginations go far enough, and they offer nothing new to the main argument over questions of personal and professional privacy when it comes to matters of the press. And Charles’s choice over whether to sign the bill is not exactly Paul Scofield’s Sir Thomas More searching his conscience over whether to sign the Oath of Supremacy to Robert Shaw’s King Henry VIII in A Man for All Seasons, but what is? The most interesting character is Jess, perhaps because she is fictional; maybe Bartlett and Goold would have fared better had they turned this into a roman a clef instead. Pigott-Smith (Educating Rita, Enron) is at his best when Charles is trying to figure out just where his responsibilities now lay, to both the royal family and England itself, but the story ultimately lets him down. King Charles III was an intriguing idea, but the execution, much like the real Prince Charles’s public persona, turns out to be rather dull and unsurprising.