Students cheer on their Hogwarts house in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (photo by Manuel Harlan)

Lyric Theatre

214 West 43rd St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Wednesday – Sunday through May 12, 2019, $80-$199 per part

www.harrypottertheplay.com/us

www.lyricbroadway.com

In the interest of full disclosure, I have an embarrassing public confession to make: I have not read a single page of any Harry Potter book, nor have I seen any of the films. But that didn’t prevent me from having a jolly good time at Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, the two-part, nearly $70 million extravaganza that is scheduled to run at the completely refurbished Lyric Theatre through May 2019. Yes, there were plenty of occasions when many audience members, including lots of kids in Potter garb, laughed, gasped, sighed, and applauded for reasons unbeknownst to me, but Tony winner Tiffany (Once, Black Watch) does an excellent job of making Potter neophytes feel more than welcome; in addition, a cheat sheet in the Showbill identifies the main characters and outlines the timeline of events from the books. The five-hour epic was written by Jack Thorne, based on an original story by Potter creator J. K. Rowling, writer Jack Thorne, and Tiffany. The show begs everyone who sees it to #KeepTheSecrets, and I fully intend to; any character- or plot-related information I divulge can be found on the official website, so I will do my best to give away nothing more.

Harry (Jamie Parker) has to help get the gang out of trouble in Broadway extravaganza (photo by Manuel Harlan)

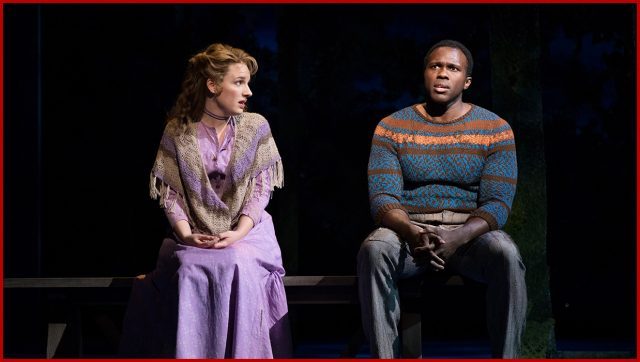

If you don’t want to know anything about the plot or which characters are even part of the story, you should skip this paragraph, but it could serve as necessary context for those unfamiliar with the Potter universe. Harry Potter and the Cursed Child takes place nineteen years after the seventh and final book, 2007’s Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Harry (Jamie Parker) is married to Ginny (Poppy Miller) and working at the Ministry of Magic. They have three children, the youngest being Albus (Sam Clemmett), who is not particularly thrilled to bear the legacy of his legendary father. That’s all the specifics you’re going to get out of me, except that Noma Dumezweni is Hermione Granger, Paul Thornley plays Ron Weasley, Alex Price is Draco Malfoy, and Anthony Boyle is terrific as his son, Scorpius. The cast also includes Jessie Fisher, Susan Heyward, Geraldine Hughes, Edward James Hyland, Byron Jennings, and David St. Louis in key roles, but to tell you who they’re portraying would give far too much away. Suffice to say that Thorne and Tiffany do a great job of giving everyone their due.

Much of the magic is orchestrated by Hagrid (Brian Abraham) in Harry Potter epic at the Lyric Theatre (photo by Matthew Murphy)

The play builds steadily, with each act more exciting than the previous one, although there is some repetition, in addition to more than a bit of questionable science regarding the time-space continuum. Christine Jones’s sets, which range from the Hogwarts facade to the Forbidden Forest, from a Quidditch match to platform 9¾, change with the help of a large ensemble cast in full costumes (by Katrina Lindsay), moving across the stage to music by Imogen Heap in choreographed near-dances by Steven Hoggett, involving suitcases, a rolling ladder, and other objects in fun ways; you’ll expect the players to break out into song at any moment, but fortunately they don’t. As the tension grows, so does the magic (designed by Jamie Harrison), which is primarily analog, avoiding too much high-tech, although there are moments of dazzling projections, shifting characters, and — well, I’m not going to tell you about that, or that, or that, either, but you’ll love it. Be sure to wander around the lobby during intermission, where there are lots of visual treats, from the wallpaper to the carpeting. One of my favorite moments actually occurred outside the Lyric, which features a glowing billboard and a child in a nest high above. I had arrived at the theater early so watched the crowd as it lined up and prepared to go through the scanners. I then saw one of the actors walking down the street and approach the stage door. The security guard asked a small group of costumed girls to wait as the actor went into the theater. The girls paid the actor no mind; little did they know that pure evil had just made room for pure evil. Such are the many secrets of this clever little play, which took London by storm and is now doing the same on Broadway.