Bryan Cranston takes on iconic role of madman Howard Beale in stage version of Network (photo by Jan Versweyveld, 2018)

Belasco Theatre

111 West 44th St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday – Saturday through March 17, $49 – $399

networkbroadway.com

When it was released in 1976, Sidney Lumet’s Network instantly shocked audiences as it unmasked the approaching intersection of the corporatization of entertainment and news in the media, featuring a brilliant, prescient script by Bronx native Paddy Chayefsky that skewered the television industry and Americans’ obsession with “the tube.” It revealed a world dominated by ratings-hungry white men in suits, with two exceptional white female characters boldly asserting their own personal and professional power and independence at the height of the women’s liberation movement. Four decades later, the story is as relevant and shocking as ever in Ivo van Hove’s riveting yet dizzying stage production, which opened last night at the Belasco.

The film was nominated for ten Oscars, winning acting awards for the late Peter Finch, Faye Dunaway, and Beatrice Straight and Best Original Screenplay for Chayefsky, who wrote such other gems as Marty, The Hospital, The Americanization of Emily, and Altered States before passing away in 1981 at the age of fifty-eight. Despite Bryan Cranston’s mesmerizing lead performance and all of van Hove’s live-streaming technical wizardry — which can be breathtaking and exhilarating as well as overwhelming, distracting, anachronistic, and confusing — it’s Chayefsky’s words that steal the show, adapted here by Lee Hall like they are gospel, which in many ways they are. In the published version of the play, which debuted at London’s National Theatre in November 2017, Hall describes his adaptation as “keyhole surgery,” writing, “Hopefully my interventions are invisible to the untrained eye.” The only significant changes involve the treatment of terrorists by the media, which Hall and van Hove tone down here, and the addition of a coda following the climactic finale. (Hall was given access to Chayefsky’s archives, so he has noted that any and all changes were based on or inspired by the author’s notes, letters, drafts, etc.)

Howard Beale (Bryan Cranston) is downtrodden as Max Schumacher (Tony Goldwyn) looks distraught in Ivo van Hove’s high-tech Broadway version of Network (photo by Jan Versweyveld, 2018)

Olivier, Emmy, and Tony winner Cranston (Breaking Bad, All the Way) takes on the iconic role of Howard Beale, portrayed so memorably by Finch in the film. Cranston immerses himself in the role with a careful abandon; he pays tribute to Finch while making the part his own, much as Hall and van Hove treat the movie. After twenty-five years with Union Broadcasting Systems, Beale is being put out to pasture because of low ratings. But he surprises everyone when he announces during a broadcast that he is going to commit suicide live on television the next week. His best friend and longtime colleague, news division president Max Schumacher (Tony Goldwyn), puts him back on the air quickly so he can apologize and restore his dignity, but Beale instead calls “bullshit” on the state of the world, sending everyone into a tizzy — except ruthlessly ambitious programming head Diana Christensen (Tatiana Maslany), who jumps on the unique opportunity and soon convinces executive producer Harry Hunter (Julian Elijah Martinez), network executive Nelson Chaney (Frank Wood), and network head Frank Hackett (Joshua Boone) to give Beale his own show, making him a kind of angry prophet of the airwaves, speaking for and to the common person. The contemporary of industry legends Walter Cronkite, Eric Sevareid, and Edward R. Murrow becomes a ranting and raving populist hero, although Schumacher believes Beale is being turned into a fool, but there’s little he can to do stop the momentum, which eventually falls apart all by itself.

The use of live video, something van Hove has done in such previous productions as The Damned at Park Avenue Armory and A View from the Bridge and The Crucible.) Depending on where you are sitting, the cameras, operated by technicians Gina Daniels, Nicholas Guest, Jeena Yi, and Joe Paulik, may also occasionally block your view. The footage is projected onto a large screen at the back, often turning Beale into a giant, his image repeating into the distance. Period news reports about Patty Hearst and old commercials — with Roy Scheider in a Folgers ad and Cranston himself pitching Preparation H — fly by on a wall of screens on one side, but don’t get too caught up in them or you’ll miss the magnificent dialogue. The set, by van Hove’s partner, Jan Versweyveld, includes a bar and nightclub-like tables and couches at stage left (where audience members who pay $299 to $399 enjoy dinner and drinks curated by former White House pastry chef Bill Yosses while watching the show and even interacting with the characters) and the glassed-in control room at stage right, where various executives, some of the tech crew, and the announcer (Henry Stram) can always be seen, as if everyone is both under surveillance and doing the surveilling.

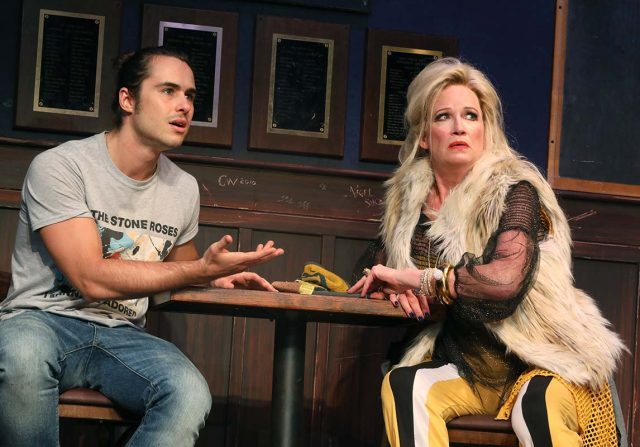

Diana Christensen (Tatiana Maslany) and Harry Hunter (Julian Elijah Martinez) can’t believe what they’re seeing in Network (photo by Jan Versweyveld, 2018)

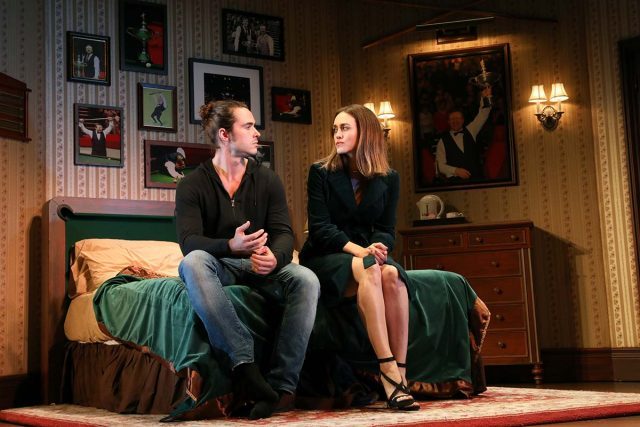

When Beale implores his television audience to open their windows and scream, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore,” van Hove shows numerous people doing only the latter; instead of photographing men and women yelling out their windows, a procession of YouTube-like selfie videos follow, seeming out of time and place. The live video even extends outdoors when Max and Diana go for a stroll, but the scene takes you out of the play as passersby gawk at Goldwyn (Scandal, Ghost) and Emmy winner Maslany (Orphan Black, Mary Page Marlowe), who never quite catch the fire and passion of William Holden and Dunaway in the film, a critical relationship that literally puts the news and entertainment divisions in bed together. Goldwyn is otherwise solidly effective as Beale’s determined protector, and the pivotal showdown between Max and his wife, Louise (Alyssa Bresnahan), hits the right notes; however, Bresnahan looks so much like Dunaway that you can’t help but wonder if she should have played Diana. (Coincidentally, Dunaway just announced she will be returning to Broadway next year, portraying Katharine Hepburn in Tea at Five.) In a fine casting touch, Barzin Akhavan plays both Jack Snowden, the young anchor in line to replace Beale, and the warm-up guy for Beale’s circuslike show, a newsman transformed into carnival barker.

News division president Max Schumacher (Tony Goldwyn) and programming head Diana Christensen (Tatiana Maslany) bring their work home with them in Network) (photo by Jan Versweyveld, 2018)

But it’s Chayefsky’s sparkling language that reigns supreme all these years later; Beale’s pronouncements ring as true now as they did in 1976. Take this speech, for example: “I don’t have to tell you things are bad. Everybody knows things are bad. Everybody’s out of work or scared of losing their job, the dollar buys a nickel’s worth, banks are going bust, shopkeepers keep a gun under the counter, punks are running wild in the streets, and there’s nobody anywhere who seems to know what to do and there’s no end to it. We know the air’s unfit to breathe and our food is unfit to eat and we sit and watch our teevees while some local newscaster tells us today we had fifteen homicides and sixty-three violent crimes, as if that’s the way it’s supposed to be. We all know things are bad. Worse than bad. They’re crazy. It’s like everything’s going crazy. So we don’t go out anymore. We sit in the house and slowly the world we live in gets smaller and all we ask is, please, at least leave us alone in our own living rooms. Let me have my toaster and my teevee and my hair dryer and my steel belted radials, and I won’t say anything, just leave us alone. Well, I’m not going to leave you alone. I want you to get mad.” When he mentions Russia, the audience laughs, but Hall isn’t making a cheap joke about current events; the reference is in the film.

In another Beale rant, it’s as if Chayefsky saw the coming of smartphones, the internet, and social media: “Because less than three percent of you people read books. Because less than fifteen percent read newspapers. Because the only truth you know is what you get on your television. There is a whole and entire generation right now who never knew anything that didn’t come out of this tube. This tube is gospel. This tube is the ultimate revelation. This tube can make or break presidents, popes, and prime ministers. This tube is the most awesome goddam force in the whole godless world! And woe is us if it ever falls into the hands of the wrong people.”

When Jensen makes his remarkably foresighted proclamation to Beale about power, international commerce, and “the primal forces of nature,” devilishly delivered by Wyman (Catch Me If You Can, A Tale of Two Cities), van Hove puts Jensen above everyone else on a heavenly platform, as if he’s a godlike figure who is the only one who understands what is really happening in the world — in 1976 as well as in 2018. Be sure to get to the Belasco early, as the actors are already traversing the stage, preparing for the evening news, as the audience enters the theater, and stay in your seats after the curtain call, as there’s a bonus that brings the visionary satire right up to the present moment, although that point has already frighteningly shone through over and over again.