Adam Driver and Keri Russell star in Broadway revival of Lanford Wilson’s Burn This (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Hudson Theatre

139-141 West 44th St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through July 14, $59 – $315

855-801-5876

www.thehudsonbroadway.com

Adam Driver is scorching hot and Keri Russell sizzles in Michael Mayer’s otherwise surprisingly lukewarm revival of Lanford Wilson’s Burn This, which opened last week at the Hudson Theatre. Oscar and Emmy nominee Driver is deserving of a Tony nod for his ferociously physical, incendiary performance as Pale, a Jersey restaurant manager unable to deal with the tragic death of his younger brother Robbie, a gay dancer who was killed in a boating accident with his lover, Dom. The play is set in 1987 and takes place in a huge industrial loft apartment in Lower Manhattan where Robbie lived with fellow dancer Anna (Russell), a straight woman in a relationship with successful screenwriter Burton (Tony nominee David Furr), and Larry (Tony nominee Brandon Uranowitz), a wisecracking gay man who works in advertising. One night Pale shows up drunk, loudly complaining about New York City, parking, phone messages, new shoes, social politeness, and anything else that comes to mind, rattling on without a filter. He constantly uses words about heat when talking about himself and his life, declaring that his “feet are in boiling water,” he has a toaster oven for a stomach, his normal temperature is about 110, and it’s hot enough in the apartment for them to “bake pizza.” He says he’s “a roving fireman. Very healthy occupation. I’m puttin’ out somebody’s else’s fire. I’m puttin’ out my own. . . . Or sometimes you just let it burn.”

Despite her better judgment, Anna, who is branching out as a choreographer, is strangely attracted to Pale, who is a stark contrast to the more self-contained Burton, who lives in Canada and is always talking about the cold, including snow and “glacier activity”; the only time he brings up heat is when he tells Anna about her upcoming dance, “Make it as personal as you can. Believe me, you can’t imagine a feeling everyone hasn’t had. Make it personal, tell the truth, and then write ‘Burn this’ on it.” Here Wilson is describing his own process in writing the play; it was indeed personal, inspired partly by the death of a friend’s brother, as well as the AIDS epidemic claiming the lives of so many New York artists. He wrote “Burn this” at the top of every page until he realized it should be the title of the play.

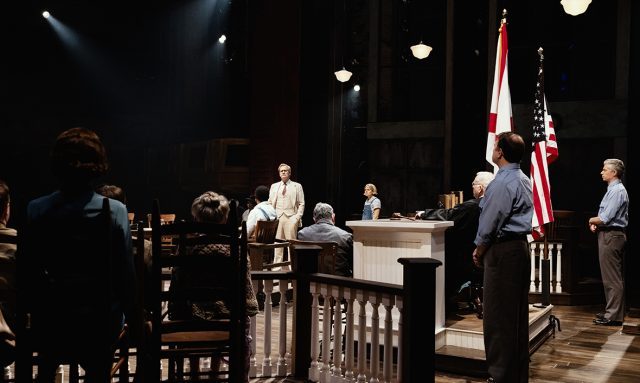

Burton (David Furr), Anna (Keri Russell), and Larry (Brandon Uranowitz) have a brief moment to cool down in Burn This at the Hudson Theatre (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Despite the strong cast, led by Lortel Award winner Driver (BlacKkKlansman, Look Back in Anger), whose body commands the stage with an intense, dangerous fury, and Golden Globe winner and Emmy nominee Russell (The Americans, Fat Pig), who has a sweet tenderness as Anna, the play never catches fire. Derek McLane’s set is lovely, with large back windows that look out on the city, an outside world that the characters can’t reach yet, and Clint Ramos’s costumes are sexy and alluring, from Pale’s sharp suits to Anna’s slinky dresses and hapi coat. The unending references to hot and cold, fire and ice grow tiresome, including the leitmotif of Bruce Springsteen’s “I’m on Fire”; would Larry really sing that? Pulitzer Prize winner Wilson (Talley’s Folly, Angels Fall) and Tony winner Mayer (Spring Awakening, Hedwig and the Angry Inch) also incorporated Springsteen songs into a 1984 revival of 1965’s Balm in Gilead. The play made its Broadway debut in 1987, running for more than a year at the Plymouth Theatre, with John Malkovich as Pale and a Tony-winning Joan Allen as Anna. A 2002 revival at the Signature paired Edward Norton and Catherine Keener. In order for the play to work, it has to have the fire and passion at least reminiscent of A Streetcar Named Desire, but this production, even with its powerful moments and strong performances, too often simmers when it needs to blister and blaze.