Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance tackles issues of gay eroticism, literature, and legacy over six and a half hours (photo by Matthew Murphy for MurphyMade, 2019)

Ethel Barrymore Theatre

243 West 47th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Wednesday – Sunday through June 7, $39 – $199

theinheritanceplay.com

Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance is a terrific two-and-a-half-hour play — however, it runs six and a half hours in two lengthy installments at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, each of which requires separate admission. Angels in America meets The Boys in the Band by way of E. M. Forster’s Howards End in the epic drama, which broke the record for winning the most Best Play awards in the West End, including four Oliviers (Best Play, Best Actor for Kyle Soller, Best Director for Stephen Daldry, and Best Lighting Design by Jon Clark). The play is set in contemporary New York City, where Eric Glass (Soller) and Toby Darling (Andrew Burnap) are in love and are considering marriage after seven years together. Toby is a beautiful, magnetic, hard-partying writer who is turning his coming-of-age novel, Loved Boy, into a play; the more grounded Eric works for Jasper (Kyle Harris), a social justice entrepreneur. Eric and Toby are friends with an urbane, wealthy older couple, Walter Poole (Paul Hilton) and Henry Wilcox (John Benjamin Hickey), who host fabulous gatherings at their summer place in the Hamptons. Fate brings actor Adam McDowell (Samuel H. Levine) into Toby’s life; Toby quickly thinks Adam should star in his play. But when Toby meets bedraggled street prostitute Leo (Levine), a double for Adam, various relationships start swirling out of control.

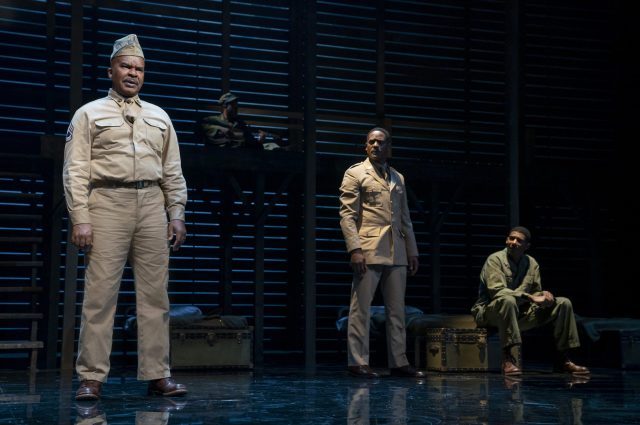

Eric Glass (Kyle Soller) and Henry Wilcox (John Benjamin Hickey) talk about life and love as E. M. Forster (Paul Hilton) looks on in Olivier Award winner (photo by Matthew Murphy for MurphyMade, 2019)

Throughout the play, Forster (Hilton) comments on the plot and interacts with some of the characters, as if he’s the omniscient narrator of a novel. Early on, a Greek chorus of young men speak with Forster about Howards End. “It’s a great book, don’t get me wrong. And the movie’s good. But, I mean, the world is so different now. I can’t identify with it at all,” one man says. “It’s been a hundred years,” adds another. “The world has changed so much,” a third points out. “Our lives are nothing like the people in your book,” a fourth chimes in. Forster asks, “How can that be true? Hearts still love, don’t they? And break. Hope, fear, jealousy, desire. Your lives may be different. But surely the feelings are the same. The difference is merely setting, context, costumes. But those are just details.” Lopez is referring to his play itself, a modern-day reimagining of Howards End that has been transformed into a gay fantasia. The difference in context matters very much, however, and is brought into sharp focus by the presence of Forster, a closeted homosexual who did not have sex until he was thirty-eight and died in 1970 at the age of ninety-one. He would not allow his own gay fantasia, the queer novel Maurice, written in 1912, to be published until after his death, a fact that is discussed in the play, which also deals directly with the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s.

Hilton (Peter Pan, Anatomy of a Suicide) is sensational as both Forster and Walter; when he reappears onstage after a lengthy absence, the audience erupts into applause, and with good reason: He is essential to the narrative, which too often drifts into melodrama that would even make Douglas Sirk cringe. Levine (Kill Floor) makes a poignant Broadway debut as Adam and Leo, switching between two characters that are polar opposites of each other. Soller is superb as the thoughtful and caring Eric, displaying a tender chemistry with Tony winner Hickey (The Normal Heart, Love! Valour! Compassion!), whose Henry is the seasoned sage of the group and whose painful memories of those lost to AIDS leads to one of the play’s most searing moments. (Hickey will be on hiatus through April 22 to make his directing debut with Plaza Suite and will be replaced by Tony Goldwyn.) Daldry (Billy Elliot, Skylight) tries to keep things moving on Bob Crowley’s minimal set, a large platform around which Eric and Toby’s friends and wannabe writers (including Jonathan Burke, Carson McCalley, Jordan Barbour, Darryl Gene Daughtry Jr., Dylan Frederick, and Arturo Luís Soria) hang out, watch the action, and interject, getting more in the way than adding worthwhile dialogue.

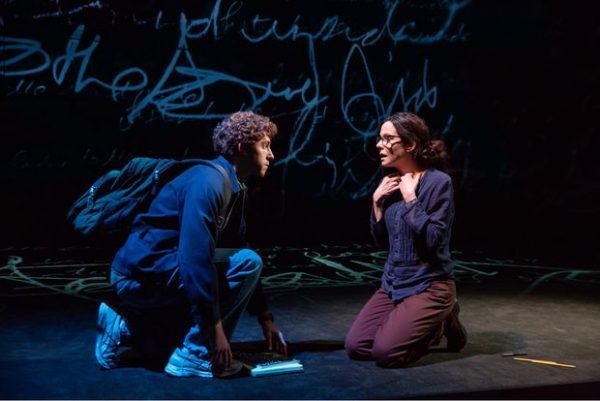

Henry Wilcox (John Benjamin Hickey) has some sharp things to say to the younger generation in Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance (photo by Matthew Murphy for MurphyMade, 2019)

“With personal relationships. Here is something comparatively solid in a world full of violence and cruelty,” Forster wrote in his seminal 1938 essay “What I Believe,” continuing, “Not absolutely solid, for Psychology has split and shattered the idea of a ‘Person,’ and has shown that there is something incalculable in each of us, which may at any moment rise to the surface and destroy our normal balance. We don’t know what we are like. We can’t know what other people are like. How, then, can we put any trust in personal relationships, or cling to them in the gathering political storm? In theory we cannot. But in practice we can and do.” Lopez (The Whipping Man, The Legend of Georgia McBride) captures that part of Forster’s ethos but also strays from it too often.

There is also a very noticeable lack of women in the story, and only one onstage, the key figure of Margaret, played by the impeccable Lois Smith (The Trip to Bountiful, Marjorie Prime), who sums it all up at the end, but by that time Lopez has long bit off more than he can chew, taking on too much and losing focus of the main plot in favor of emotionally manipulative scenes that lack the necessary subtlety even as he tackles such intense subjects as gay eroticism, class, sex, AIDS, and, most critically, legacy. The Inheritance is filled with delicate, beautiful scenes that will move you deeply, unforgettable moments that exemplify what makes live theater so potent. But it just can’t sustain itself for six and a half hours.