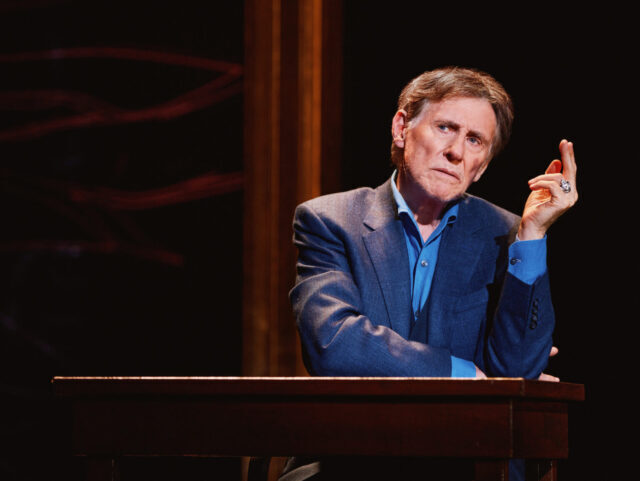

You might experience déjà vu when watching Sir Tom Stoppard’s Leopoldstadt on Broadway (photo by Joan Marcus)

LEOPOLDSTADT

Longacre Theatre

220 West 48th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 12, $74-$318

leopoldstadtplay.com

The Broadway premiere of Sir Tom Stoppard’s Olivier Award–winning Leopoldstadt has just about everything going for it: The exquisite production features a terrific cast of more than thirty actors, stunning sets by Richard Hudson, elegant costumes by Brigitte Reiffenstuel, superb lighting by Neil Austin, strong sound and original music by Adam Cork, and powerful direction by Patrick Marber. So why is it ultimately unsatisfying?

Named for the second municipal district of Vienna where a tight-knit community of Jews lived, the play is based on real events that Stoppard’s family experienced. Yet it was not until 1993 that Stoppard, born Tomáš Sträussler in the Czech Republic in 1937, learned that he had several Jewish relatives who had been killed in concentration camps during the Holocaust. The play’s narrative runs from December 1899 to January 1890, the spring of 1924, November 1938, to 1955 as the Merz-Jakobovicz clan goes from prosperity to persecution.

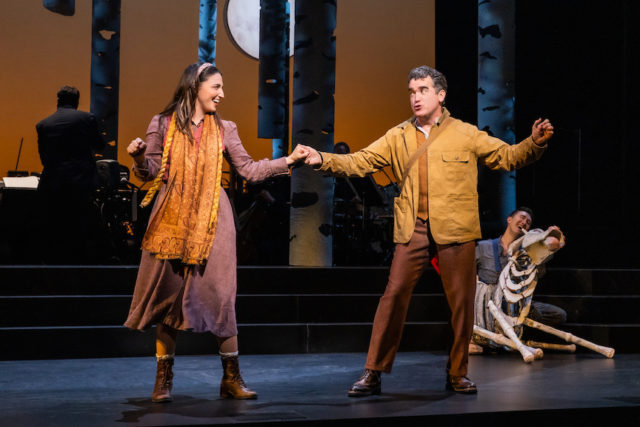

The story begins with family and servants readying for Christmas, including decorating the tree. Prophetically, the first lines uttered are “That’s mine!” by young Rosa (Pearl Scarlett Gold), followed by young Pauli (Drew Squire) declaring, “And that’s mine!” In a span of a few decades, the family will lose nearly everything.

The men discuss Freud, religion, and marrying out of the faith. Assimiliation is clearly the theme. Eva Merz Jakobovicz (Caissie Levy) says, “We’re Jews. Bad Jews but pure-blood sons of Abraham, and Ludwig’s parents would have nothing to do with us if their grandson didn’t look Jewish in his bath. In fact, if I’d had myself Christianised like my brother, Ludwig wouldn’t have married me, would you, be honest.” Erudite mathematician Ludwig (Brandon Uranowitz), Eva’s husband, responds, “I would when they were dead.” Eva asks, “Is that a compliment?”

The Jewish Merz-Jakobovicz family decorates their Christmas tree in Leopoldstadt (photo by Joan Marcus)

A moment later, Hermann Merz (David Krumholtz), Wilma Jakobovicz Kloster (Jenna Augen) and Ludwig’s brother, married to the Christian Gretl, (Faye Castelow), tells Ludwig, “You seem to think becoming a Catholic is like joining the Jockey Club.” Ludwig quickly retorts, “It’s not unlike, except that anyone can become a Catholic.”

To fill in the family’s background further, Stoppard has Wilma accuse Hermann of disdaining Grannie and Grandpa Jakobovicz. “You’re snobby about their accent and using Yiddish words, and dressing like immigrants from some village in Galicia,” she proclaims. “There’s too much of the shtetl about them for you.”

As the years pass by, there are affairs and betrayals, the birth of new generations, key business decisions, such Jewish rituals as a Passover Seder and a bris, the coming of the Nazis, and a gathering of Holocaust survivors.

While the discovery of his Jewish heritage deeply affected Stoppard (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, The Invention of Love, The Coast of Utopia), who has won four Tonys, three Oliviers, and an Oscar, Leopoldstadt adds nothing new to the genre of Holocaust-related dramas. Most of the scenes are nobly rendered, but I felt like I had seen too many of them before, especially when Umzugshauptmannsleiter Schmidt (Corey Brill) invades the family home and, dare I say, a word entered my mind that it rarely does in Stoppard’s work: cliché.

From Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, Ken Burns’s The U.S. and the Holocaust, and the 1978 Holocaust television miniseries to Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, Roberto Benigni’s Life Is Beautiful, Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy, and Jane Campion’s The Pianist, the oppression of the Jews by the Third Reich has been explored from multiple angles and emotions, each adding fresh insight, which is disappointingly lacking in Leopoldstadt.

In 1938, Ernst (Aaron Neil), who is married to Wilma, discusses a trio of paintings by Gustav Klimt (one of which the family owns): “A dream is the fulfilment in disguise of a suppressed wish. The rational is at the mercy of the irrational. Barbarism will not be eradicated by culture. The last time I saw Freud, the most profound man I know, I asked him, ‘Yes, but why the Jews?’ He said, ‘I don’t know, Ernst. I wasn’t going to ask you, but — why the Jews?’” It’s a question that’s been asked over and over, and answered; I was expecting more from Stoppard.

While technically a marvel and certainly worth seeing, the widely hailed Leopoldstadt does not reach the pantheon of its predecessors, neither in its genre nor its author’s oeuvre. Even midlevel Stoppard is an event to be treasured, but don’t be surprised when you have déjà vu at the Longacre Theatre.