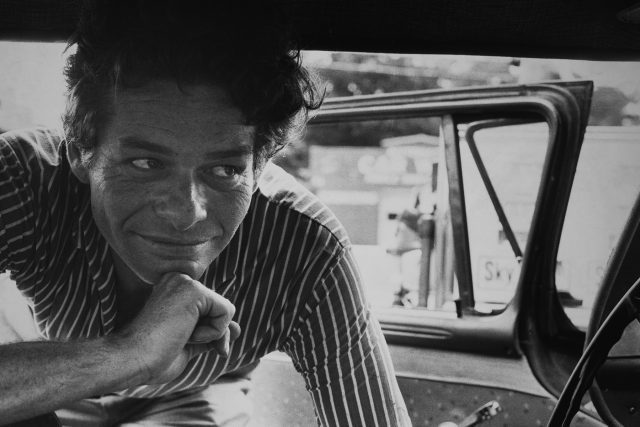

New documentary paints a fascinating portrait of street photographer Garry Winogrand (photo by Judy Teller)

GARRY WINOGRAND: ALL THINGS ARE PHOTOGRAPHABLE (Sasha Waters Freyer, 2018)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Opens Wednesday, September 19

212-727-8110

www.winograndmovie.com

filmforum.org

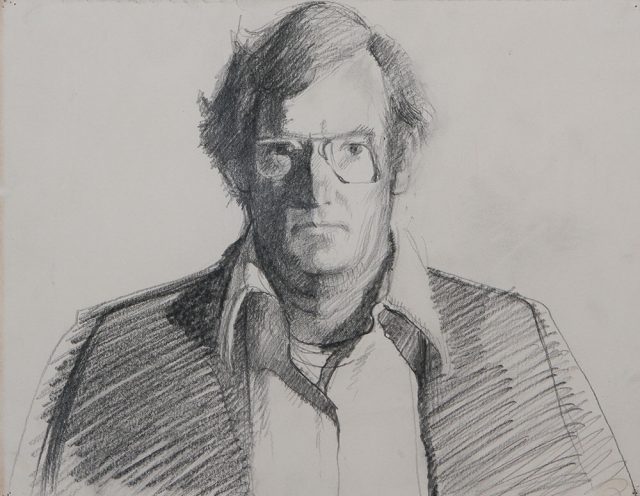

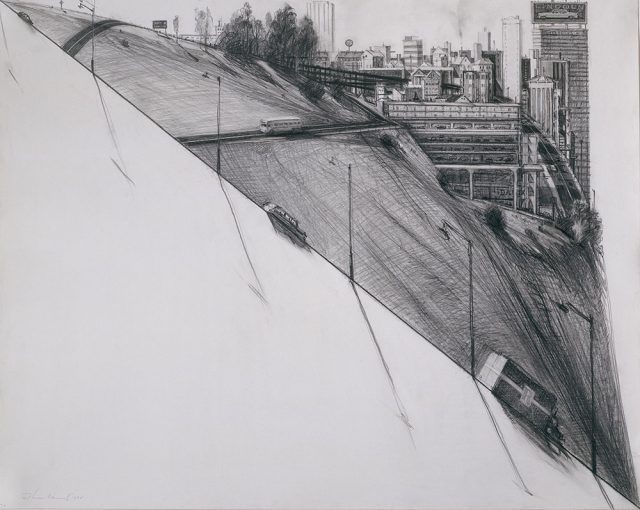

There’s an intrinsic challenge about making a documentary about a photographer: How to portray the artist’s work, silent, still pictures of a moment in time, in a medium based on sound and movement. In Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable, producer, director, and editor Sasha Waters Freyer attacks that issue by delving deep into many of Winogrand’s photographs, lingering on them as friends, relatives, and colleagues rave about his glorious images. “Well, what is a photograph? I’ll tell you what a photograph is. It’s the illusion of a literal description of how a camera saw a piece of time in space,” Winogrand said in a 1975 lecture at the University of Texas Austin, later adding, “All it is is light on surface.” Of course, in Winogrand’s case, it is much more than that; the black-and-white pictures he took with his trusted Leica M4 inhale and exhale at the exciting pace of real life. “It’s this observation of human behavior, of human activity, human gesture, the relationships between people, whether they know each other or not, how we behave in the world,” curator Susan Kismaric says. Writer Geoff Dyer calls Winogrand’s work a “psychogestural ballet,” while photographer Matt Stuart looks at photo after photo, pointing out “the dance” in each one. “When things move, I get interested. I know that much,” Winogrand, who passed away in 1984 at the age of fifty-six, says in his gruff voice. “He had no ambition for fame or celebrity. He was totally obsessed and possessed by photography,” his good friend, photographer Tod Papageorge, says. “It was work work work work work.”

There’s an intrinsic challenge about making a documentary about a photographer: How to portray the artist’s work, silent, still pictures of a moment in time, in a medium based on sound and movement. In Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable, producer, director, and editor Sasha Waters Freyer attacks that issue by delving deep into many of Winogrand’s photographs, lingering on them as friends, relatives, and colleagues rave about his glorious images. “Well, what is a photograph? I’ll tell you what a photograph is. It’s the illusion of a literal description of how a camera saw a piece of time in space,” Winogrand said in a 1975 lecture at the University of Texas Austin, later adding, “All it is is light on surface.” Of course, in Winogrand’s case, it is much more than that; the black-and-white pictures he took with his trusted Leica M4 inhale and exhale at the exciting pace of real life. “It’s this observation of human behavior, of human activity, human gesture, the relationships between people, whether they know each other or not, how we behave in the world,” curator Susan Kismaric says. Writer Geoff Dyer calls Winogrand’s work a “psychogestural ballet,” while photographer Matt Stuart looks at photo after photo, pointing out “the dance” in each one. “When things move, I get interested. I know that much,” Winogrand, who passed away in 1984 at the age of fifty-six, says in his gruff voice. “He had no ambition for fame or celebrity. He was totally obsessed and possessed by photography,” his good friend, photographer Tod Papageorge, says. “It was work work work work work.”

![New York, 1968 [laughing woman with ice cream] Photographs by Garry Winogrand, Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.](https://twi-ny.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/garry-winogrand-2-e1537325349352.jpg)

“New York, 1968” [laughing woman with ice cream] (photographs by Garry Winogrand, Collection Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco)

Freyer traces the life of “a city hick from the Bronx,” from his boyhood, when he had polio, through three marriages and three children, from his fear of nuclear war to his love of the female form, from the streets of New York City to California and Texas. She weaves in audio and video from lectures and interviews, filmed and taped conversations with photographer Jay Maisel, and photos and home movies of Winogrand and his family. Freyer speaks with photographers Thomas Roma, Jeffrey Henson Scales, Leo Rubinfien, Laurie Simmons, and Michael Ernest Sweet, curator Erin O’Toole, gallery owner Jeffrey Fraenkel (who compares Winogrand to Norman Mailer), Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner, historian and critic Shelley Rice, and two of Winogrand’s ex-wives, Adrienne Lubeau and Judy Teller. There are also extensive quotes from legendary MoMA photography curator John Szarkowski. The film explores several turning points in his career, both good and bad, including the “New Documents” show with Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus; his seminal work in 1964; “The Animals,” a series shot at the Central Park Zoo, where he would go with his kids; his color work; Public Relations, in which he examined the role and effect of the mass media; and his controversial Women Are Beautiful book, which was labeled as sexist and misogynistic.

Influenced by such photographers as Robert Frank, Walker Evans, and Dan Weiner, Winogrand could not stop taking pictures. He took so many — the thought of his working in the digital age is both thrilling and frightening — that he didn’t even develop thousands of rolls, leaving behind a treasure trove of material that Roma explains was misinterpreted by critics. “I would like not to exist,” Winogrand said. It’s a good thing for the rest of us that he did, sharing his unique view of the world, incorporating the chaos of his personal life into his remarkable pictures. Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable, which features original music by Winogrand’s son, Ethan, and animation by Kelly Gallagher, opens September 19 at Film Forum, with Freyer participating in Q&As following the 7:00 shows on September 19 and 21. In her director’s statement, the Brooklyn-born Freyer writes, “In looking at Winogrand in all his multidimensional human complexity, I take aim at the ‘bad dad’ and ‘bad husband’ tropes in artist biography, seeking to undermine these as sources of triumph or artistic necessity. Winogrand was an artist whose rise and fall — from the 1950s to the mid-1980s — in acclaim mirrors not only that of American power and credibility in the second half of the twentieth century but also a vision of American masculinity whose limitations, toxicity, and inheritance we still struggle, culturally, to comprehend. The film ultimately invites a deeper consideration of Winogrand not only as a ‘man of his time,’ in the words of MoMA photography curator Susan Kismaric, but also as a man struggling to define himself simultaneously as an artist and a parent (as so many of us do).”

I remember the buzz in the room back in July 2012 at the press preview for the “Yayoi Kusama” retrospective at the old Whitney. Even among all the jaded art critics, there was palpable excitement at the rumor that Kusama herself might be attending the event. Alas, it was not to be. But now everyone can feel like they’re in the same room as the iconoclastic Japanese artist when watching Heather Lenz’s infinitely entertaining documentary, Kusama: Infinity, opening September 7 at Film Forum. Over the course of her seven-decade career, Kusama has explored the concepts of infinity and eternity through painting, sculpture, performance art, film, and installation, highlighted by an obsession with endless circles and mirrored reflections. “I convert the energy of life into dots of the universe. And that energy along with love flies into the sky,” she explains. Traumatic childhood experiences deeply influenced her life and art; she began painting when she was eight years old in rural Matsumoto City, where her unhappy parents ran a wholesale seed business (and her mother would tear up her drawings). Now eighty-nine, she still works every day, going from the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill, where she has lived voluntarily since 1977, to her studio, which is filled with her captivating works-in-progress. Lenz zooms in for extreme close-ups of the artist surrounded by canvases, as if she is the biggest dot (or seed?) in her universe. “So much of Kusama’s art seeks to re-create that [childhood] experience in one form or another,” notes Alexandra Munroe, senior curator of Asian Art at the Guggenheim. “It is literally an experience of being lost into her physical environment, of losing her selfhood in this space that is moving rapidly, and expanding rapidly.”

I remember the buzz in the room back in July 2012 at the press preview for the “Yayoi Kusama” retrospective at the old Whitney. Even among all the jaded art critics, there was palpable excitement at the rumor that Kusama herself might be attending the event. Alas, it was not to be. But now everyone can feel like they’re in the same room as the iconoclastic Japanese artist when watching Heather Lenz’s infinitely entertaining documentary, Kusama: Infinity, opening September 7 at Film Forum. Over the course of her seven-decade career, Kusama has explored the concepts of infinity and eternity through painting, sculpture, performance art, film, and installation, highlighted by an obsession with endless circles and mirrored reflections. “I convert the energy of life into dots of the universe. And that energy along with love flies into the sky,” she explains. Traumatic childhood experiences deeply influenced her life and art; she began painting when she was eight years old in rural Matsumoto City, where her unhappy parents ran a wholesale seed business (and her mother would tear up her drawings). Now eighty-nine, she still works every day, going from the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill, where she has lived voluntarily since 1977, to her studio, which is filled with her captivating works-in-progress. Lenz zooms in for extreme close-ups of the artist surrounded by canvases, as if she is the biggest dot (or seed?) in her universe. “So much of Kusama’s art seeks to re-create that [childhood] experience in one form or another,” notes Alexandra Munroe, senior curator of Asian Art at the Guggenheim. “It is literally an experience of being lost into her physical environment, of losing her selfhood in this space that is moving rapidly, and expanding rapidly.”