Ryuichi Sakamoto extends his legacy with jaw-dropping Kagami at the Shed (photo courtesy Tin Drum)

KAGAMI

The Griffin Theater at the Shed

The Bloomberg Building at Hudson Yards

545 West 30th St. at Eleventh Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through July 9, $33-$38

646-455-3494

theshed.org

“I honestly don’t know how many years I have left,” composer, musician, producer, and environmental activist Ryuichi Sakamoto says in the 2017 documentary Coda. “But I know that I want to make more music. Music that I won’t be ashamed to leave behind. Meaningful work.”

The Tokyo-born Oscar and Grammy winner died this past March 28 at the age of seventy-one, but that doesn’t mean you won’t be able to see him perform live — sort of — ever again. Over the last nine years of his life, Sakamoto battled various types of cancer. Knowing his time on Earth was limited, he continued working, releasing the album async in 2017 and 12 just before his death, composing the scores for such films as The Revenant, Rage, The Fortress, and Love After Love, and preparing the cutting-edge project Kagami, which opens today at the Shed in Hudson Yards.

On the wall outside the theater, Sakamoto writes:

There is, in reality, a virtual me.

This virtual me will not age, and will continue to play the piano for years, decades, centuries.

Will there be humans then?

Will the squids that will conquer the earth after humanity listen to me?

What will pianos be to them?

What about music?

Will there be empathy there?

Empathy that spans hundreds of thousands of years.

Ah, but the batteries won’t last that long.

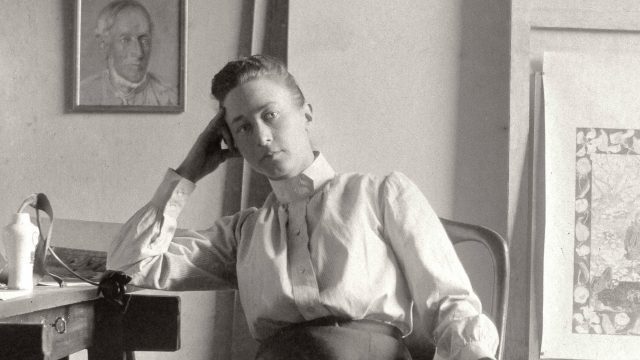

Ryuichi Sakamoto, director Todd Eckert, and Rhizomatiks work behind the scenes on Kagami (photo courtesy Tin Drum)

Kagami is a spectacular, breathtaking mixed-reality concert experienced with specially designed optically transparent devices, making it appear that Sakamoto is playing live piano, enveloped in augmented reality art. Visitors are first led into a room in the repurposed Griffin Theater with large-scale posters of Sakamoto and a screening of clips from Coda, in which he wanders through a lush forest and the Arctic, searching for the harmonies and melodies of nature. Sitting by a hole in the ice, he dips a microphone into the water and says, “I’m fishing with sound.”

The group of no more than eighty next enter another space, where chairs are set up in one row around a central area with cubic markings on the floor. Each person receives tight-fitting goggle-like glasses and, suddenly, a hologram of Sakamoto appears in the middle of the room, seated at his Yamaha grand piano; he was volumetrically captured in December 2020, during the height of Covid, by director Todd Eckert and his Tin Drum collective, which previously made the mixed-reality installation The Life with Marina Abramović.

The audience is warned before the show starts that the technology is not perfect — it turns out that the hologram is not very sharp, and it’s difficult to understand what Sakamoto says in brief introductions to two of the songs — but it’s jaw-droppingly gorgeous nonetheless. The fifty-minute concert begins with the jazzy “Before Long” from the 1987 album New Geo; as the white-haired Sakamoto tickles the ivories, smoky clouds rise from the floor and float in the air. Near the end of the number, one audience member got up and walked over to the image of Sakamoto at the piano. A few others, including me, soon joined him, and more followed. As Sakamoto played the ethereal, New Agey “Aoneko no Torso” from 1995’s Smoochy, I approached Sakamoto and slowly sauntered around the piano, seeing the maestro from all different angles, close enough to determine the length of his fingernails and follow his eye movement. Even though he’s slightly out of focus, it’s hard to believe he’s not really right there, questioning reality itself as a construct. Although you could walk through him, no one did, as if out of respect.

Experience KAGAMI, the remarkable final staged concert by legendary composer and artist Ryuichi Sakamoto at The Shed (@theshedny).

Four weeks only, June 7 – July 2

Previews are sold out.https://t.co/cJ2sRG9gZS#Kagami#ryuichisakamoto#skmtnews#TinDrum#dbSoundscape pic.twitter.com/sv9sjm2n31— ryuichi sakamoto (@ryuichisakamoto) May 25, 2023

Over the next several songs, ranging from “The Seed and the Sower” and the title track from the 1983 film Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, “Andata” from async, “Energy Flow” and “Aqua” from 1999’s BTTB, and “MUJI2020” from the “Pleasant, somehow” campaign about humanity’s responsibility to the environment, raindrops created ripples in a pond at our feet; diagonal neon lights hovered ominously over our heads; snowflakes fluttered by; multiple screens projected archival black-and-white footage of old cities and a snowstorm; and a tree grew out of the piano, its roots then digging far into the ground, mimicking the circulatory system. The highlight was when the Griffin became like the Hayden Planetarium, with stars and constellations everywhere and the spinning earth underneath, making me feel like I was floating in the air, a wee bit dizzy until I let the music bring me back.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the technology is its ability to essentially allow you to see right through anyone standing in front of you. At a concert with a real pianist, if a tall person gets in your way, you can’t see the performer. But here, they are like ghosts; you can make out their outlines but still have a clear path to Sakamoto. Of course, the other people are actually there, so you have to avoid bumping into them by using your peripheral vision.

Kagami means “mirror” in Japanese, and the show certainly makes you look at who you are both as an individual and as part of the greater environment. The special effects cause sensations reminiscent of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s thrilling Infinity Rooms, which use lights and mirrors to extend visions of our universe. The presentation is no mere money grab by an estate trying to resurrect their dead cash cow with posthumous holographic tours. Kagami is an intricately designed multimedia installation that the artist was deeply involved in; Sakamoto fashioned his own unique legacy, pushing the boundaries yet again, playing one last concert that can last forever, or at least as long as the planet he so loved and protected is still here and the batteries last.