Carrie Mae Weems, “Untitled (Kitchen Table Series),” gelatin silver print and text, 1953 (© Carrie Mae Weems. Photo: © The Art Institute of Chicago)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Ave. at 89th St.

April 25-27, most events free with museum admission of $18-$22, evening concerts $15-$35

Exhibition continues through May 14

212-423-3587

www.guggenheim.org

In her online biography, Carrie Mae Weems writes, “My work has led me to investigate family relationships, gender roles, the histories of racism, sexism, class, and various political systems. Despite the variety of my explorations, throughout it all it has been my contention that my responsibility as an artist is to work, to sing for my supper, to make art, beautiful and powerful, that adds and reveals; to beautify the mess of a messy world, to heal the sick and feed the helpless; to shout bravely from the roof-tops and storm barricaded doors and voice the specifics of our historic moment.” All this and more is evident in her current exhibition at the Guggenheim, ”Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video.” The show, which continues through May 14, is centered by her subtly powerful 1990 black-and-white “Kitchen Table Series,” which details the evolution of a woman photographed in the same domestic space, sometimes by herself, sometimes with children, sometimes with a man. In many ways it harkens back to painting series by Jacob Lawrence, capturing the African American experience, in this case with the focus on a woman. The show also includes photos from her “Colored People” grids, “Family Pictures and Stories” (accompanied by a voice-over by Weems), “Dreaming in Cuba,” “Roaming,” “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” “The Louisiana Project,” and “Sea Islands Series” in addition to such short films as Afro-Chic and ceramic commemoration plates, all of which explore elements of black history from an often extremely personal perspective.

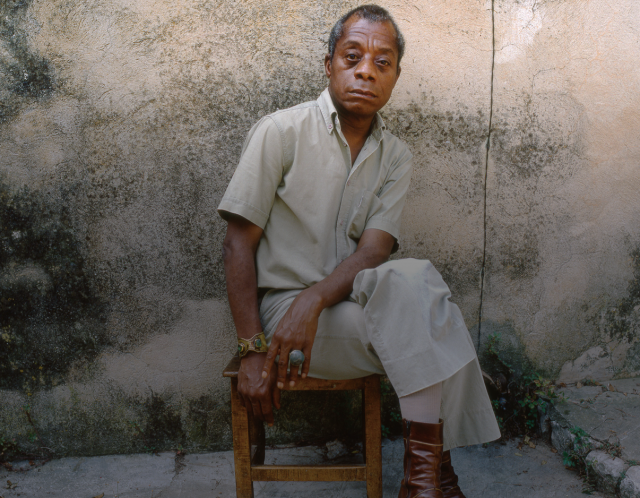

Carrie Mae Weems will cohost three days of art and activism at the Guggenheim this weekend (photo by Scott Rudd)

The Portland, Oregon-born artist will be at the Guggenheim this weekend presenting “Carrie Mae Weems LIVE: Past Tense/Future Perfect,” three days of discussions, live music, processions, readings, and more, cohosted by Weems and multidisciplinary artist Carl Hancock Rux. On Friday, there will be a tribute to conceptual sculptor and saxophonist Terry Adkins, who passed away at the age of sixty in February, with Vijay Iyer, Vincent Chancey, Dick Griffin, Marshall Sealy, and Kiane Zawadi, followed by “The Blue Notes of Blues People,” consisting of four sets of presentations by such visual artists, curators, choreographers, and scholars as Julie Mehretu, Leslie Hewitt, Shinique Smith, Thomas Lax, Michele Wallace, Camille A. Brown, Shahzia Sikander, Mark Anthony Neal, Sanford Biggers, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Xaviera Simmons. Other programs include “Written on Skin: Posing Questions on Beauty,” “Slow Fade to Black: Explorations in the Cinematic,” and “Laughing to Keep from Crying: A Critical Read on Comedy,” with Nelson George. The first two nights will conclude with ticketed concerts and conversations, with Jason Moran and the Bandwagon (Friday, with Weems) and the Geri Allen Trio (Saturday, with Weems and Theaster Gates). on Sunday, visual artist María Magdalena Campos-Pons will lead the procession “Habla Lamadre” before Weems offers closing remarks. Select programs on Friday and Saturday will be streamed live here.

Italian auteur Marco Bellocchio reimagines the kidnapping of Aldo Moro from the inside in Good Morning, Night, a taut, slow-paced drama that won the Little Golden Lion at the 2003 Venice Film Festival. Moro, a former Italian prime minister and president of the Christian Democratic Party, was boldly grabbed by members of the radical Red Brigades, who left a bloody mess in their wake. Bellocchio focuses on the three men and one woman who orchestrated the plot and kept Moro locked in a hidden room inside their large rented apartment. While Mariano (Luigi Lo Cascio), Ernesto (Pier Giorgio Bellocchio), and Primo (Giovanni Calcagno) take turns guarding Moro and Mariano spews Socialist rhetoric at him, Chiaras (Maya Sensa), who is Primo’s girlfriend but is pretending to be Ernesto’s wife as a cover, goes to work every day, buys supplies and newspapers, and dreams at night of Moro coming to her as a father figure. Chiaras is the moral conscience of the movie, and a complete invention on the part of Bellocchio, who has said, “I’m not interested in the factual truth.” Even so, much of the real story is still not known, and like the JFK assassination, there are lots of conspiracy theories out there about an event that shocked a nation. Pink Floyd fans get a bonus by Bellocchio’s powerful use of “The Great Gig in the Sky” and “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.” Good Morning, Night is screening on April 25 at 4:00 as part of the MoMA’s Bellocchio retrospective, held in conjunction with the upcoming U.S. release of his latest film, Dormant Beauty, which opens June 6 at Lincoln Plaza. The series continues through May 7 with such other Bellocchio works as Henry IV, The Devil in the Flesh, Fists in the Pocket, China Is Near, Vincere, and Dormant Beauty.

Italian auteur Marco Bellocchio reimagines the kidnapping of Aldo Moro from the inside in Good Morning, Night, a taut, slow-paced drama that won the Little Golden Lion at the 2003 Venice Film Festival. Moro, a former Italian prime minister and president of the Christian Democratic Party, was boldly grabbed by members of the radical Red Brigades, who left a bloody mess in their wake. Bellocchio focuses on the three men and one woman who orchestrated the plot and kept Moro locked in a hidden room inside their large rented apartment. While Mariano (Luigi Lo Cascio), Ernesto (Pier Giorgio Bellocchio), and Primo (Giovanni Calcagno) take turns guarding Moro and Mariano spews Socialist rhetoric at him, Chiaras (Maya Sensa), who is Primo’s girlfriend but is pretending to be Ernesto’s wife as a cover, goes to work every day, buys supplies and newspapers, and dreams at night of Moro coming to her as a father figure. Chiaras is the moral conscience of the movie, and a complete invention on the part of Bellocchio, who has said, “I’m not interested in the factual truth.” Even so, much of the real story is still not known, and like the JFK assassination, there are lots of conspiracy theories out there about an event that shocked a nation. Pink Floyd fans get a bonus by Bellocchio’s powerful use of “The Great Gig in the Sky” and “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.” Good Morning, Night is screening on April 25 at 4:00 as part of the MoMA’s Bellocchio retrospective, held in conjunction with the upcoming U.S. release of his latest film, Dormant Beauty, which opens June 6 at Lincoln Plaza. The series continues through May 7 with such other Bellocchio works as Henry IV, The Devil in the Flesh, Fists in the Pocket, China Is Near, Vincere, and Dormant Beauty.

Barbara Stanwyck delivers one of her most nuanced and beguiling performances as the tough-talking title character in The Lady Eve. Usually lumped in with her classic screwball comedies, Preston Sturges’s black-and-white film, based on an original story by Irish playwright Monckton Hoffe (who was nominated for an Oscar), is much darker and slower than its supposed brethren. A brunette Stanwyck is first seen as Jean Harrington, a con artist looking to trick a wealthy man on a cruise ship. At her side is her father, “Colonel” Harrington (Charles Coburn), a gambler and a cheat. As soon as Jean sees rich ale scion Charles Pike (a wonderfully innocent Henry Fonda), she digs her claws into the shy, humble man, challenging the Hays Code as she shows off her gams and leans into him with a heart-pounding sexiness. Pike of course falls for, but when his right-hand man, Muggsy (William Demarest), discovers that she regularly preys on suckers, Charles is devastated. However, in this case, Jean’s feelings might actually be real, forcing her to go to extreme circumstances to try to get him back. Stanwyck is, well, a ball of fire as Jean/Eve, determined to win at all costs. Fonda, not usually known for his comedic abilities, is a riot as poor Hopsie, as Jean calls him; the looks on his face when she ratchets up the sex appeal are priceless, and a later scene when he keeps falling down at a party displays a surprising flair for physical comedy. The opening and closing credits feature a corny animated snake in the Garden of Eden; in The Lady Eve, Stanwyck offers the apple, and Fonda can’t wait to take a bite. And there’s nothing shameful about that. The Lady Eve is screening April 25-27 at 11:00 am as part of the IFC Center series “American Hustlers: Grifters, Swindlers, Scammers & Cheats” series, which concludes May 2-4 with Stephen Frears’s The Grifters.

Barbara Stanwyck delivers one of her most nuanced and beguiling performances as the tough-talking title character in The Lady Eve. Usually lumped in with her classic screwball comedies, Preston Sturges’s black-and-white film, based on an original story by Irish playwright Monckton Hoffe (who was nominated for an Oscar), is much darker and slower than its supposed brethren. A brunette Stanwyck is first seen as Jean Harrington, a con artist looking to trick a wealthy man on a cruise ship. At her side is her father, “Colonel” Harrington (Charles Coburn), a gambler and a cheat. As soon as Jean sees rich ale scion Charles Pike (a wonderfully innocent Henry Fonda), she digs her claws into the shy, humble man, challenging the Hays Code as she shows off her gams and leans into him with a heart-pounding sexiness. Pike of course falls for, but when his right-hand man, Muggsy (William Demarest), discovers that she regularly preys on suckers, Charles is devastated. However, in this case, Jean’s feelings might actually be real, forcing her to go to extreme circumstances to try to get him back. Stanwyck is, well, a ball of fire as Jean/Eve, determined to win at all costs. Fonda, not usually known for his comedic abilities, is a riot as poor Hopsie, as Jean calls him; the looks on his face when she ratchets up the sex appeal are priceless, and a later scene when he keeps falling down at a party displays a surprising flair for physical comedy. The opening and closing credits feature a corny animated snake in the Garden of Eden; in The Lady Eve, Stanwyck offers the apple, and Fonda can’t wait to take a bite. And there’s nothing shameful about that. The Lady Eve is screening April 25-27 at 11:00 am as part of the IFC Center series “American Hustlers: Grifters, Swindlers, Scammers & Cheats” series, which concludes May 2-4 with Stephen Frears’s The Grifters.