Walter Lee Younger (Denzel Washington) and Ruth (Sophie Okonedo) are just trying to survive day to day in stellar revival of A RAISIN IN THE SUN (photo by Brigitte Lacombe)

Ethel Barrymore Theatre

243 West 47th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 15, $67 – $149

www.raisinbroadway.com

Broadway revivals are often about star power, still-relevant socioeconomic or –political issues, or inventive staging of a familiar classic. But Kenny Leon’s new version of A Raisin in the Sun goes back to the very creation of this fifty-five-year-old American drama, celebrating its fascinating author, Lorraine Hansberry. As patrons enter the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, an interview with Hansberry, the first African American woman to have a work produced on Broadway, is being broadcast on the sound system. Each Playbill comes with an additional pamphlet that reprints “Sweet Lorraine,” James Baldwin’s 1969 Esquire remembrance of Hansberry — who died in 1965 at the age of thirty-four — in which he writes, “Black people ignored the theater because the theater had always ignored them. But, in Raisin, black people recognized that house and all the people in it — the mother, the son, the daughter, and the daughter-in-law — and supplied the play with an interpretative element which could not be present in the minds of white people: a kind of claustrophobic terror, created not only by their knowledge of the streets.” Leon’s production, and the extremely talented cast, honors every word of the play, which doesn’t feel old-fashioned in any way.

Walter Lee Younger (Denzel Washington) explains his questionable plans to his mother (LaTanya Richardson Jackson) in A RAISIN IN THE SUN (photo by Brigitte Lacombe)

Oscar and Tony winner Denzel Washington stars as Walter Lee Younger, a dreamer trying to lift his family out of poverty in their cramped apartment on Chicago’s South Side. Every morning there’s a battle to get to the bathroom across the hall, shared by everyone on the floor. Walter’s mother, Lena (LaTanya Richardson Jackson), is expecting a $10,000 insurance check for her recently deceased husband. While Walter wants to invest it in a liquor store with his friends Bobo (Stephen McKinley Henderson) and the never-seen Willy Harris, Walter’s hardworking wife, Ruth (Sophie Okonedo), wants to put it to far more practical use. Also awaiting the money are Walter and Ruth’s son, Travis (Bryce Clyde Jenkins), who sleeps on the couch, and Walter’s sister, Beneatha (Anika Noni Rose), who lives with them as well and wants to become a doctor. As Beneatha spends time with two different men, the assimilating George Murchison (Jason Dirden) and Joseph Asagai (Sean Patrick Thomas), who introduces her to her African roots, Lena considers moving the family to all-white Clybourne Park, leading to a visit by neighborhood leader Karl Lindner (David Cromer), setting in motion a series of events that, with a delicate balance of humor and tragedy, intelligently capture the black experience in mid-twentieth-century America. (A Raisin in the Sun was a direct influence on Bruce Norris’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Clybourne Park.)

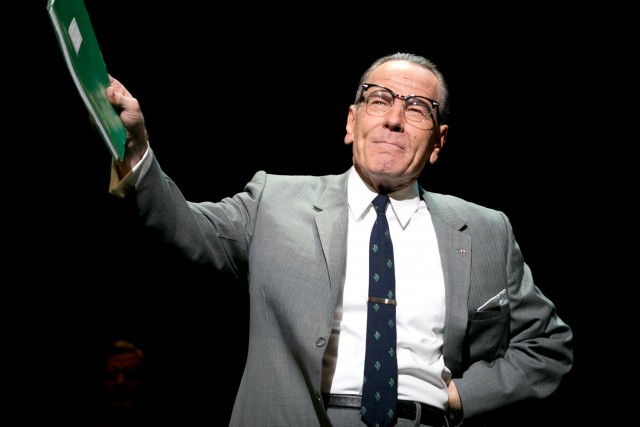

A representative from Clybourne Park (Karl Lindner) has some surprising news for the Younger family (photo by Brigitte Lacombe)

Washington (Fences, Julius Caesar), in a role created by Sidney Poitier first onstage and then in the 1961 film, is a whirlwind as Walter, practically dancing as he weaves his way through Mark Thompson’s apartment set, his gait displaying a slight jump, his leg often shaking in anticipation of making things better for him and his family. Okonedo embodies the sadness of the everyday drudgery her life encompasses, her eyes tired before their time, heavy with what could have been. Jackson is a fireball as the caring matriarch who wants to see her children and grandson succeed. Hansberry’s words flow like poetry as the Youngers’ path is continually blocked, evoking the Langston Hughes poem that gave the work its title, “A Dream Deferred”: “What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up / like a raisin in the sun? / Or fester like a sore — / And then run?” It was only ten years ago that Leon brought A Raisin in the Sun to the Royale, with a cast that included Sean Combs, Audra McDonald, Phylicia Rashad, and Sanaa Lathan, but this stellar current production makes the previous one but a distant memory, injecting fresh new life into one of Broadway’s most historically and socially important works.

Filmed in black-and-white over three years in multiple locations and ultimately employing five cinematographers, four editors, three Desdemonas, and two scores, it’s rather amazing that Orson Welles’s 1952 independent production of William Shakespeare’s Othello was ever completed — of course, many Welles projects were not. That the final work turned out to be a masterpiece that won the Palme d’Or at Cannes speaks yet more to Welles’s genius. A newly restored version of Othello is in the midst of a two week-run at Film Forum, in conjunction with “Celebrate Shakespeare 2014!,” a worldwide festival honoring the Bard’s 450th birthday. Welles, who directed the picture and plays the title character, streamlined the story into ninety-five minutes, getting to the heart of the most intense tale of jealousy and betrayal ever told. The film opens with shadowy shots of the dead Othello and his deceased wife, Desdemona (Suzanne Cloutier), carried aloft on biers at their dual funeral, to the sounds of an ominous piano and a mournful vocal chorus. The credits soon follow, after which Welles returns to the beginning, as the villainous ensign Iago (Micheál MacLiammóir) plots with Roderigo (Robert Coote) to convince Othello that his loyal and devoted wife is actually in love with the heroic soldier Michael Cassio (Michael Laurence).

Filmed in black-and-white over three years in multiple locations and ultimately employing five cinematographers, four editors, three Desdemonas, and two scores, it’s rather amazing that Orson Welles’s 1952 independent production of William Shakespeare’s Othello was ever completed — of course, many Welles projects were not. That the final work turned out to be a masterpiece that won the Palme d’Or at Cannes speaks yet more to Welles’s genius. A newly restored version of Othello is in the midst of a two week-run at Film Forum, in conjunction with “Celebrate Shakespeare 2014!,” a worldwide festival honoring the Bard’s 450th birthday. Welles, who directed the picture and plays the title character, streamlined the story into ninety-five minutes, getting to the heart of the most intense tale of jealousy and betrayal ever told. The film opens with shadowy shots of the dead Othello and his deceased wife, Desdemona (Suzanne Cloutier), carried aloft on biers at their dual funeral, to the sounds of an ominous piano and a mournful vocal chorus. The credits soon follow, after which Welles returns to the beginning, as the villainous ensign Iago (Micheál MacLiammóir) plots with Roderigo (Robert Coote) to convince Othello that his loyal and devoted wife is actually in love with the heroic soldier Michael Cassio (Michael Laurence).