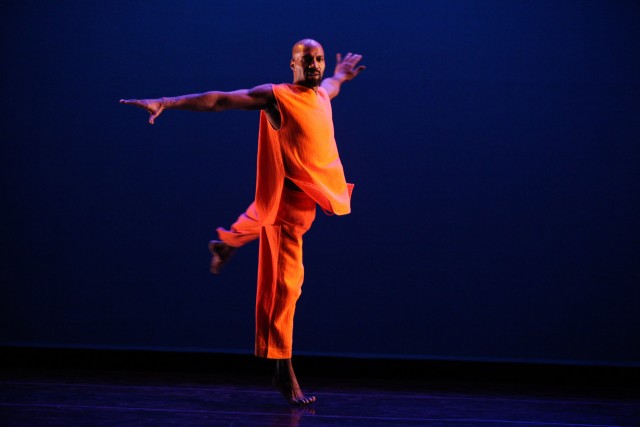

Ronald K. Brown will celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Evidence, a Dance Company, at the Joyce starting February 24 (photo by Ayodele Casel)

EVIDENCE, A DANCE COMPANY

Joyce Theater

175 Eighth Ave. at 19th St.

February 24 – March 1, $10-$49

212-242-0800

www.joyce.org

www.evidencedance.com

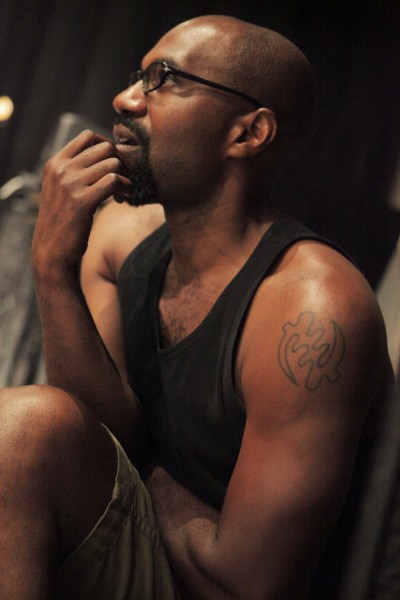

When he was in second grade, Brooklyn-born dancer and choreographer Ronald K. Brown wanted to be Arthur Mitchell, the first African American to dance with the New York City Ballet and founder of the Dance Theatre of Harlem. In 1985, Brown, then only nineteen, formed his own troupe, which he named Evidence, a Dance Company, to honor family, ancestors, teachers, tradition, faith, and the African diaspora. From February 24 through March 1, Brown, who has also choreographed works for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Muntu Dance Theater of Chicago, and Ballet Hispanico in addition to The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess on Broadway, will be celebrating his company’s thirtieth anniversary with a pair of special programs at the Joyce. Program A includes 2014’s The Subtle One, about experiencing the love of another, with live music by Selma composer Jason Moran and the Bandwagon; the gorgeous Grace, created for Alvin Ailey in 1999; and the excerpts “Exotica” and “March” from 1995’s Lessons, the latter set to the words of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., performed by Annique Roberts and Coral Dolphin. Program B comprises the Evidence premiere of 2014’s Why You Follow/Por Que Sigues, commissioned for Havana’s MalPaso Dance Company (who will be at the Joyce March 3-8); 1999’s Gatekeepers, a piece originally for Philadanco that delves into Native American mythology and African traditions; excerpts from 2007’s multimedia One Shot: Rhapsody in Black & White, inspired by Pittsburgh photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris; and the New York premiere of Brown’s 2014 solo piece, Through Time and Culture, which brings a unique perspective to his long career. A charming and engaging Guggenheim Fellow and dedicated Brooklynite who is currently an artist in residence at BRIC in Fort Greene, where Evidence will perform in November 2015, Brown recently discussed his life and career, particularly about these past ten years.

twi-ny: Back in 2005, we had lunch together and talked about your twentieth anniversary season. How has the last decade treated you and Evidence?

Ronald K. Brown: The time has been full since that conversation ten years ago. These past ten years have brought Evidence and me more than we could have imagined. In 2010, we had a U.S. State Department tour as a part of DanceMotion/USA and went to Senegal, Nigeria, and South Africa; we were gone for twenty-nine days, performed five times, and taught classes for all ages during our time away. We did have one day off in Grahamstown, South Africa, and were able to go on a safari and relax . . . but the work was great.

I choreographed my first work for Chicago’s Muntu Dance Theatre, and The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, which opened first at the American Repertory Theater and then on Broadway.

In November 2013, Evidence moved our offices to Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, so for the first time our rehearsals, summer workshops, and daily administrative operations are in the same building — down the hall. That feels great.

twi-ny: Back then, you said, “We have to find out what’s going on in the world. We can’t be disconnected and feel like we’re safe.” How does that relate to you and your work today?

RKB: One thing that I have also learned is that we have to make sure we are connected to those close to us . . . and then that opens up the capacity to be connected to the world. In one of our pieces, On Earth Together, we added dancers from the community in Brooklyn for performances a couple years ago, in South Bend, Indiana, last week, and right now in Pittsburgh. Creating a large cast, talking about grief and compassion, unlocks things that bring the cast closer together . . . and then we can share that compassion with the issues that are happening in the world. Just in talking about the work in South Bend, first an elder confessed that she had lost her husband a month prior. The next day a ten-year-old boy broke down; he had lost his granny two years prior. Then another elder confessed that she had recently lost her husband. And finally, on the last night, a mother and daughter who were in the cast mentioned to [associate artistic director] Arcell [Cabuag] that this particular night was the anniversary of them losing her other daughter. So here we are in this dance, On Earth Together, and the compassion and support was real onstage. Then we could talk about the other things that were going on in the world that were in the recent news.

I’m grateful for the openness of folks who come to the audition and the classes, not knowing that there will be a space to share themselves in a safe place.

twi-ny: From February 24 through March 1, you’ll be presenting your thirtieth anniversary season, at the Joyce. How did you go about choosing which of your pieces will be part of the two programs?

RKB: When we put a program together, we want the evening to have a flow that makes sense. That feels right. I also want to make sure there is a range in the work, things that are new but with something different added, like having The Subtle One being performed live with composer Jason Moran and his group the Bandwagon. I also want to make sure there is work that has not been seen in a while and again with an added surprise. This year the male duet “March” will be danced by two women.

twi-ny: What was the impetus behind creating your new solo piece, “Through Time and Culture”?

RKB: Through Time and Culture was commissioned last year by the American Dance Festival. I wanted to build a solo that demonstrated a sense of perseverance and pressing through, because of the support that family and teachers have given me.

I selected music that would allow me to show the connections of dances from around the world. The dance also is a way that I could breathe the stages of grief as I dealt with the transition of my father to join the ancestors a couple years ago, and my mother in 1996.

Ronald K. Brown will perform a solo piece as part of anniversary season at the Joyce (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

twi-ny: You travel around the world, adding elements of African movement to your work. Where have you been recently that has influenced your choreography?

RKB: My last two trips to Havana, in 2013 and 2014, definitely had an impact on the work. Seeing the social, folklore, and contemporary dance and work helped me understand more fully what I do, similar to seeing artists in Nigeria during that 2010 trip, where I saw B-Boys, breakdancers, folks improvising, traditional artists, young people showing Evidence some dances from Atlanta, and a choreographer who has been creating Contemporary African Dance for over fifteen years. All these moments helped me understand the expansion of the dance world and what is possible.

The lessons are really to continue to study and then go in to the studio to create, grateful to have an increased sense of freedom with more techniques and rhythms to call on.

twi-ny: You’ve now choreographed five pieces for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Is your approach to that different from how you choreograph for Evidence?

RKB: When I choreograph on Ailey, or any other company, for the most part I create something that is specifically for them. I generally have three weeks to set a work on Ailey; that first day I am teaching material so that I can identify two casts, and by Wednesday I need to provide a list of dancers selected for the piece. With such a set deadline up front, I come to the studio with some material to teach.

With Evidence on the first day . . . I have the title . . . some music . . . and perhaps some written text and images that I use to fuel the movement that will come once I get in the zone of discovery . . . in the moment and dance it out. This cannot happen with Ailey until I have cast it.

The great thing about Ailey is that the artistic staff there continues to give me time to clean up and clarify things in further rehearsals before the New York season and U.S. or European tours.

In Evidence, the dancers will let me know that I can continue to clarify and shape the piece and make changes to allow the piece to be . . . what it is meant to be, and as long as I am not taking time away from us rehearsing repertory. For the most part, Evidence agrees. . . . “Ron, finish the new work and we will do our homework for when you are ready to rehearse us in the older work.”

twi-ny: You mentioned earlier choreographing the Broadway revival of Porgy and Bess. Do you have any future plans for more Broadway productions?

RKB: This past fall Arcell Cabuag and I worked with director/writer Moises Kaufman on an Afro-Cuban musical version of Carmen. It premiered at the University of Miami, with four professional actors from New York and the other roles played by students form the theater department of U of M. I’m not sure what the life of the piece will be after that, ideally a regional theater further development of the work and hopefully a Broadway run. But that is the hope, who the creative team will be. . . .

A couple years ago I met with a company that commissions works for Broadway and I have begun thinking of some ideas and will begin writing something soon. I will look for collaborators when the time is right.

But right now, I’m focused on Evidence and our upcoming season at the Joyce, a project at Williams College, and a new work for Ailey in 2015. I am also talking to a company in Detroit about setting something. If someone comes to me with a fit for Broadway and it works out time-wise, I would consider it . . . but the commitment for Porgy and Bess was major. Incredible . . . but major. The Porgy national tour was also a wonderful revisit. But the timing made sense. Complicated, but it worked out.

twi-ny: You have a special relationship with Brooklyn. You were born and raised there, and your company has been based there from the beginning, becoming an integral part of the community. And you recently moved into the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Center for Arts and Culture. How has that move gone?

RKB: The move to Restoration in November 2013 was a nice move for Evidence. In December 2014 we had to move all of our costumes and props there as well.

It feels great to have a home. We have rehearsed at Restoration for over ten years. When the company is in rehearsal down the hall, I can take care of admin assignments and then go to the studio to rehearse, give notes, and go back to my admin hat.

A few years ago, when we moved our Summer Dance Workshop Series from Medgar Evers Preparatory School to Restoration, the staff at Restoration and Arcell both saw how much sense it made for Evidence to have our educational efforts also happen at BSRC. When our office was in Fort Greene, there was the additional chore of bringing the set-up supplies to another location. Now we just walk down the hall.

I think the dancers who come from all over to take our summer workshop and/or my weekly Tuesday-night class appreciate that Evidence has a home. I also appreciate that it was the first place I took a dance class when I was eight years old and where I competed in storytelling contests; mine was the collection of Anansi the Spider. (The contests took place in the atrium, what used to be an ice-skating rink.)

twi-ny: Brooklyn has changed significantly over the last thirty years. What would you consider the best and worst parts of that change?

RKB: I know that there is an effort to increase the presence of new business and create new corridor around Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Plaza. The farmers market across the street from BSRC and some of the new businesses are wonderful assets to the community.

The worst parts are the multitude of condos going up surrounded by folks who cannot afford them. Improvements in neighborhoods for the people who live there is a beautiful thing, but when folks are displaced or outpriced . . . this is another thing. We all deserve healthy food choices and respectful neighbors.

twi-ny: Congratulations on your thirtieth anniversary. When you were a kid in Bed-Stuy, dancing at home, dressing up as Arthur Mitchell, did you ever think that things would turn out this way?

RKB: Thank you. I had no idea of how things would turn out. There are models of what is possible. Alvin Ailey, Katherine Dunham, Arthur Mitchell, Pearl Primus, but also my grandfather Ruben McFadgion. I remember two conversations I had with my Poppi; every summer we would drive down from Brooklyn to Raeford, North Carolina, where my grandfather (Poppi) was building a house.

I asked him, “Where are the plans for the house?” He responded, “I don’t need plans; I know what I want.”

This house is five bedrooms, two bathrooms, a basement the same length of the house, where we would roller skate (until he finished).

I asked, “Why is the house so big?” He said, “So you have somewhere to go.”

Flash forward: I’m in the house working on the laptop and he says, “You went to school for that? I would never be able to do that.”

My response: “No, Poppi, I did not go to school for this. . . . I think I have your genes.”

His response: “That’s right, Kevin . . . keep God first.” [ed note: Brown’s family calls him by his middle name, Kevin.]

I tell people, there is freedom in listening and obeying. I try to do that. . . . I had no idea things would turn out the way they did.

But the Most High did and does.

Award-winning film festival favorite Drunktown’s Finest is a refreshingly original look inside life on a Navajo reservation in New Mexico. “They say this land isn’t a place to live; it’s a place to leave. Then why do people stay?” asks Nizhoni Smiles (MorningStar Angeline) at the beginning of writer-director Sydney Freeland’s debut feature, which opens with a shot of a town that could be any town. The story follows three teenagers trying to improve their lot by getting off the reservation. Sick Boy (Jeremiah Bitsui), who is about to have a child with Angela Maryboy (Elizabeth Frances), is trying to stay out of trouble the weekend before joining the army. Felixia (Carmen Moore) is a transsexual model attempting to jump-start her career by appearing in a Women of the Navajo calendar. And Nizhoni decides to track down her birth family before leaving to go to college in Michigan. The lives of the three protagonists intersect in unexpected ways as outside forces — and questionable decisions — complicate their chosen paths.

Award-winning film festival favorite Drunktown’s Finest is a refreshingly original look inside life on a Navajo reservation in New Mexico. “They say this land isn’t a place to live; it’s a place to leave. Then why do people stay?” asks Nizhoni Smiles (MorningStar Angeline) at the beginning of writer-director Sydney Freeland’s debut feature, which opens with a shot of a town that could be any town. The story follows three teenagers trying to improve their lot by getting off the reservation. Sick Boy (Jeremiah Bitsui), who is about to have a child with Angela Maryboy (Elizabeth Frances), is trying to stay out of trouble the weekend before joining the army. Felixia (Carmen Moore) is a transsexual model attempting to jump-start her career by appearing in a Women of the Navajo calendar. And Nizhoni decides to track down her birth family before leaving to go to college in Michigan. The lives of the three protagonists intersect in unexpected ways as outside forces — and questionable decisions — complicate their chosen paths.

This year’s heated Oscar race features a pair of fact-based British films about two of the most intelligent and important men of the last hundred years, but their life stories couldn’t be more different. The Theory of Everything follows Oxford-born theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) as he falls in love with linguist Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones) and is stricken with motor neuron disease while at Cambridge; at the age of twenty-one he is given two years to live, but more than fifty years later he is still alive and vibrant at seventy-three, celebrated far and wide as the smartest human being on the planet. On the other hand, The Imitation Game is about London-born mathematician Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch), who died in shame and obscurity in 1954 at the age of forty-one; it would be more than fifty years before his remarkable work for the British government during WWII would be revealed to the public. In both films, the protagonist is on a scientific quest; in The Imitation Game, Turing is trying to break the seemingly unbreakable code of the Nazis’ Enigma machine, while Hawking is after nothing less than a single mathematical equation that can explain the vast universe. Both films were based on recent books, The Imitation Game on Andrew Hodges’s Alan Turing: The Enigma, and The Theory of Everything on Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen by Jane Hawking. Both films feature extensive scenes filmed on location where some of the action originally took place, The Imitation Game in Bletchley Park and The Theory of Everything at Cambridge.

This year’s heated Oscar race features a pair of fact-based British films about two of the most intelligent and important men of the last hundred years, but their life stories couldn’t be more different. The Theory of Everything follows Oxford-born theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) as he falls in love with linguist Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones) and is stricken with motor neuron disease while at Cambridge; at the age of twenty-one he is given two years to live, but more than fifty years later he is still alive and vibrant at seventy-three, celebrated far and wide as the smartest human being on the planet. On the other hand, The Imitation Game is about London-born mathematician Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch), who died in shame and obscurity in 1954 at the age of forty-one; it would be more than fifty years before his remarkable work for the British government during WWII would be revealed to the public. In both films, the protagonist is on a scientific quest; in The Imitation Game, Turing is trying to break the seemingly unbreakable code of the Nazis’ Enigma machine, while Hawking is after nothing less than a single mathematical equation that can explain the vast universe. Both films were based on recent books, The Imitation Game on Andrew Hodges’s Alan Turing: The Enigma, and The Theory of Everything on Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen by Jane Hawking. Both films feature extensive scenes filmed on location where some of the action originally took place, The Imitation Game in Bletchley Park and The Theory of Everything at Cambridge.