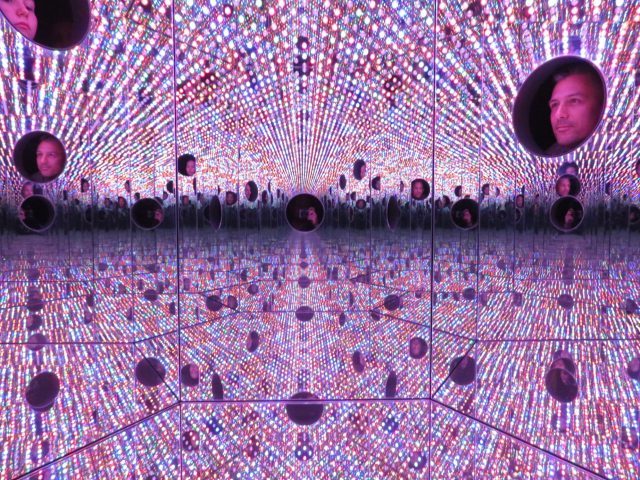

Be prepared to wait hours to get ninety seconds inside Yayoi Kusama’s 2017 “Infinity Mirrored Room — Let’s Survive Forever” (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

David Zwirner

Festival of Life: 525 & 533 West 19th St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves., through December 16

Infinity Nets: 34 East 69th St. between Park & Madison Aves., through December 22

Tuesday – Saturday, free, 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

www.davidzwirner.com

You probably should already be on line if you want to see Yayoi Kusama’s 2017 “Infinity Mirrored Room — Let’s Survive Forever,” part of her wide-ranging “Festival of Life” exhibition, which closes December 16 at David Zwirner’s Chelsea galleries. The wait times have been reaching upwards of six hours, and that will likely only increase as the end of the run approaches; you can stay updated about the line on Zwirner’s twitter feed. The approximately 12x20x20-foot carpeted room features stainless-steel balls hanging on monofilaments from the ceiling and arranged on the floor, with mirrored surfaces on all sides that seem to reflect into infinity. There is also a vertical box with three round viewing panes where visitors can look into a kaleidoscopic wonderland. Kusama, now eighty-eight, has been making the mirrored infinity rooms since 1963, when the Japanese artist was living and working in New York City. Five or six people at a time are allowed to enter the small space and spend ninety seconds there; be sure to actually experience the dazzling, brightly lit room and not just concentrate on taking selfies. In fact, each picture is a selfie because everyone inside is reflected again and again all over the room.

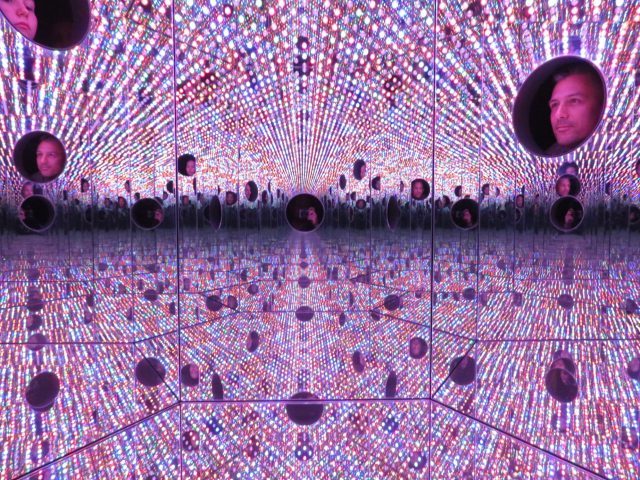

Yayoi Kusama’s “Longing for Eternity” brings people together at David Zwirner (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

There are three other sections of the exhibit that don’t require standing on line. In a dark room, the new “Longing for Eternity” rises near the center, a vertical box with four viewing holes where visitors can stick their heads inside to see more endless, ever-changing kaleidoscopes of multiple colors made of LED lights; you can also see the other people sticking their heads in the box, at different heights. You cannot put your camera or iPhone through the holes to snap a picture; if you were to drop it inside, it would break and ruin the piece. So again, just let yourself get lost in the awe-inspiring visuals and don’t worry so much about perfect documentation.

Yayoi Kusama, “With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever,” installation view, “Yayoi Kusama Eternity of Eternal Eternity,” the National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan, 2012 (image © Yayoi Kusama; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London; YAYOI KUSAMA Inc.)

You’ll next enter a captivating paradise known as “With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever,” a 2011 installation making its U.S. debut. The room is covered from floor to ceiling (including the hallway and the door) in big red polka dots on a white background; it also contains a trio of large-scale fiberglass tulips in planters that evoke the images you see when looking into Magic Eye stereograms. In fact, it can feel like you’re experiencing it through virtual reality glasses, but it’s actually right there, playing with your equilibrium in fun ways. But there’s more to it than just that; as Kusama, who combines Pop Art, Minimalism, and Abstract Expressionism and refers to herself as an Avant-Garde artist, writes in a “Message to the people of the world from Yayoi Kusama”: “Today’s world is marked by heightened anxiety connected to ever growing strife between nations and individuals, and to elusive prospects for peace. In the midst of such turmoil, we must, as human beings, be ever more vigilant and determined to build a better world through strengthened cooperation. . . . My greatest desire is that my vision of a future of eternal harmony among people be carried on.”

Yayoi Kusama’s “Festival of Life” combines “My Eternal Soul” paintings with “Flowers That Bloom Now” sculpture (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Finally, in the vast west gallery, Kusama, who works six days a week, nearly nonstop, has arranged sixty-six new paintings from her “My Eternal Soul” series, which she began in the late 2000s. Each canvas is 76.375 x 76.375 inches square, in two rows across all four walls. The works, which boast such titles as “When I Saw the Largest Dream in Life,” “Women in the Memories,” “Everyone Is Seeking Peace,” “The Far End of My Sorrow,” “A Soul Is Leaving the Body,” “Dear Death of Mine, Thou Shalt Welcome an Eternal Death,” and “Festival of Life,” contain repeated elements such as eyes, profiles, amoebalike organisms, aliens, faces, geometric patterns, and others in an endless array of colors. In the center of the room is a platform with a trio of forty-one-inch-high stainless-steel “Flowers That Bloom Now,” with long, snakelike green stems and polka-dotted petals and pistils, looking like a delightful ride in a children’s playground or amusement park (except it doesn’t rotate and you can’t go on it).

“Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Nets” has been extended at David Zwirner’s uptown space through December 22 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

There are no lines to see “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Nets” at Zwirner’s new space on East 69th St., which will afford you plenty of time to breathe in Kusama’s stunning, iconic net paintings, inspired by hallucinations she has experienced since childhood; Kusama suffers from obsessive neurosis and has been voluntarily living at Tokyo’s Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill since 1977. She first prepares the canvas in a solid color, then washes over it in a second color, her impasto brushwork evident, sometimes swirling, sometimes thick with clumps, as she makes hundreds of tiny arcs, like crescent moons or waves, in the background color. (She was influenced by a 1957 plane trip from Tokyo to Seattle, watching the ocean crests below her.) The works look different from every angle, at times offering optical illusions or what appear to be hidden figures, but that’s just your imagination getting in the flow. “My net paintings were very large canvases without compositions – without beginning, end, or center,” Kusama has said. “The entire canvas would be occupied by monochromatic nets. This endless repetition caused a kind of dizzy, empty, hypnotic feeling.” The ten works, which can be seen as traps or safety nets, include random letters in their titles that don’t actually mean anything (for example, WFCOT, BNDBS, and FWIPK), adding to the intrigue. “My desire was to predict and measure the infinity of the unbounded universe, from my own position in it, with dots — an accumulation of particles forming the negative spaces in the net. How deep was the mystery? Did infinities exist beyond our universe? In exploring these questions I wanted to examine the single dot that was my own life,” Kusama has explained. And in her unique universe, each single dot reveals the hand — and heart and mind — of the artist, a rare treat in a digital world.

“I guess there’s just a certain amount of good and bad you get from your parents and I just got the bad,” Cal (James Dean) says in Elia Kazan’s cinematic adaptation of part of John Steinbeck’s 1952 novel, East of Eden, a modern retelling of the biblical Cain and Abel story. In his first starring role, Dean received a posthumous Oscar nomination for his moody, angst-ridden performance as Cal Trask, a troubled young man who discovers that the mother (Best Supporting Actress winner Jo Van Fleet) he thought was dead is actually alive and well and running a successful house of prostitution nearby. Cal tries to win his father’s (Raymond Massey as Adam Trask) love and acceptance any way he can, including helping him develop his grand plan to transport lettuce from their farm via refrigerated railway cars, but his father seems to always favor his other son, Aron (Richard Davalos). Aron, meanwhile, is in love with Abra (Julie Harris), a sweet young woman who takes a serious interest in Cal and desperately wants him to succeed. But the well-meaning though misunderstood Cal does things his own way, which gets him in trouble with his father and brother, the mother who wants nothing to do with him, the sheriff (Burl Ives), and just about everyone else he comes in contact with.

“I guess there’s just a certain amount of good and bad you get from your parents and I just got the bad,” Cal (James Dean) says in Elia Kazan’s cinematic adaptation of part of John Steinbeck’s 1952 novel, East of Eden, a modern retelling of the biblical Cain and Abel story. In his first starring role, Dean received a posthumous Oscar nomination for his moody, angst-ridden performance as Cal Trask, a troubled young man who discovers that the mother (Best Supporting Actress winner Jo Van Fleet) he thought was dead is actually alive and well and running a successful house of prostitution nearby. Cal tries to win his father’s (Raymond Massey as Adam Trask) love and acceptance any way he can, including helping him develop his grand plan to transport lettuce from their farm via refrigerated railway cars, but his father seems to always favor his other son, Aron (Richard Davalos). Aron, meanwhile, is in love with Abra (Julie Harris), a sweet young woman who takes a serious interest in Cal and desperately wants him to succeed. But the well-meaning though misunderstood Cal does things his own way, which gets him in trouble with his father and brother, the mother who wants nothing to do with him, the sheriff (Burl Ives), and just about everyone else he comes in contact with.

A key film that helped lead 1960s cinema into the grittier 1970s, Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces is one of the most American of dramas, a tale of ennui and unrest among the rich and the poor, a road movie that travels from trailer parks to fashionable country estates. Caught in between is Bobby Dupea (Jack Nicholson), a former piano prodigy now working on an oil rig and living with a well-meaning but not very bright waitress, Rayette (Karen Black). When Bobby finds out that his father is ill, he reluctantly returns to the family home, the prodigal son who had left all that behind, escaping to a less-complicated though unsatisfying life putting his fingers in a bowling ball rather than tickling the keys of a grand piano. Back in his old house, he has to deal with his brother, Carl (Ralph Waite), a onetime violinist who can no longer play because of an injured neck and who serves as the film’s comic relief; Carl’s wife, Catherine (Susan Anspach), a snooty woman Bobby has always been attracted to; and Bobby’s sister, Partita (Lois Smith), a lonely, troubled soul who has the hots for Spicer (John Ryan), the live-in nurse who takes care of their wheelchair-bound father (William Challee).

A key film that helped lead 1960s cinema into the grittier 1970s, Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces is one of the most American of dramas, a tale of ennui and unrest among the rich and the poor, a road movie that travels from trailer parks to fashionable country estates. Caught in between is Bobby Dupea (Jack Nicholson), a former piano prodigy now working on an oil rig and living with a well-meaning but not very bright waitress, Rayette (Karen Black). When Bobby finds out that his father is ill, he reluctantly returns to the family home, the prodigal son who had left all that behind, escaping to a less-complicated though unsatisfying life putting his fingers in a bowling ball rather than tickling the keys of a grand piano. Back in his old house, he has to deal with his brother, Carl (Ralph Waite), a onetime violinist who can no longer play because of an injured neck and who serves as the film’s comic relief; Carl’s wife, Catherine (Susan Anspach), a snooty woman Bobby has always been attracted to; and Bobby’s sister, Partita (Lois Smith), a lonely, troubled soul who has the hots for Spicer (John Ryan), the live-in nurse who takes care of their wheelchair-bound father (William Challee).