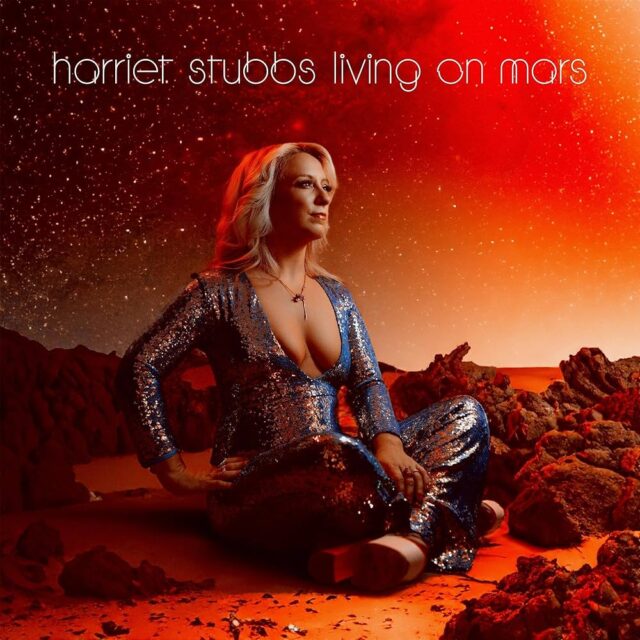

Harriet Stubbs will perform at Joe’s Pub on June 2 (Drew Bordeaux Photography)

HARRIET STUBBS

Joe’s Pub

425 Lafayette St. by Astor Pl.

Sunday, June 2, $32.50 (plus two drink or one food item minimum), 6:00

212-539-8778

www.joespub.com

www.harrietstubbs.com

“If you feel safe in the area that you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area,” David Bowie said in a 1990s video interview. “Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being in. Go a little bit out of your depth, and when you don’t feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.”

British classical pianist, William Blake scholar, and Bowie aficionado Harriet Stubbs has built her career on such advice, as evidenced by her latest album, the exciting Living on Mars; the record is the follow-up to 2018’s Heaven and Hell: The Doors of Perception, a title inspired by Aldous Huxley’s autobiographical 1954 book The Doors of Perception and 1956 essay Heaven and Hell and Blake’s 1793 tome The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Now based in London, Los Angeles, and the East Village, the British-born Stubbs took to the keys when she was three and has performed at such prestigious venues as Carnegie Hall, Le Poisson Rouge, St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Cutting Room, Tibet House, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. On June 2, she will play Living on Mars in its entirety at her Joe’s Pub debut; be sure to get a good look at her shoes, which are always spectacular.

The eclectic record features Stubbs’s unique solo adaptations of the Thin White Duke’s “Space Oddity” and “Life on Mars” as well as Nick Cave’s “Push the Sky Away,” Paul McCartney’s “Blackbird,” and Beethoven’s “Pathétique” in addition to homages to the duos of J. S. Bach/Glenn Gould and Frédéric Chopin/Leopold Godowsky.

My wife and I first became interested in Stubbs when Cave gave her a shout-out at an October 2023 show at the Beacon; earlier this month my wife saw Stubbs perform a private Coffee House Club concert at the Salmagundi Club on Fifth Ave., and then we bumped into her on the street by Sheridan Square. Clearly, our paths were destined to cross.

In this exclusive interview, Stubbs talks about Blake and Bowie, the pandemic, swimming with Cave, and playing in New York City.

twi-ny: You started your career early, first performing publicly as a pianist at the age of four and performing piano concertos as soloist at the age of nine. Growing up immersed in classical music performance, when did you become interested in contemporary pop music?

harriet stubbs: My love of music outside of classical really developed as a teenager and as I was transitioning from a career as a child prodigy to that of an adult artist: what I wanted to do with classical music, how I wanted to remain in it, why, and how these were going to come together to inform my professional adult life. A moment that I remember in particular was hearing the Verve live at Glastonbury in 2008 and realizing that it would always be music that I wanted to dedicate my life to. The thrill of a shared moment in music where everyone has been moved by the same thing is simply extraordinary.

twi-ny: That thrill was changed when the pandemic hit. During the Covid-19 crisis, you played live daily, from your London flat — 250 twenty-minute concerts. Do you have any favorite memories from that rather dark time? How did it feel to get back in front of larger audiences in person again after the lockdown ended?

hs: I think that period was so bleak that every concert in its own way was a deeply moving experience, whether it was two people in the pouring rain or two hundred. Pre-vaccine it was outside of a small window, attached to an amp attached to an upright at a busy intersection of traffic, with people very distanced and masked — who I waved at through the window.

At the time there was no end in sight, so just to have a shared experience in that way — however tentative — was needed more than ever. The two hundredth concert was in December of 2020 and the last at that address and under those circumstances in the dark and the rain. When the spring came, people were starting to be vaccinated, and as they were, I was able to offer them drinks outside; the weather was beautiful (mostly), there was a grand piano, a bay window, and a quiet, residential street where people could hear properly. Being awarded a British Empire Medal [in 2022] by the late Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was very special, as was Nick Cave showing up to hear “Push the Sky Away”! Those concerts were made by the regulars who came right up until the border opened back up for me to return to New York.

twi-ny: Speaking of Nick Cave, we recently saw him play the Beacon, and he raved about you. Your cover of “Push the Sky Away” is on your new album, Living on Mars. How did the Nick Cave connection come about?

hs: Nick and I met in a park in London a few years ago and became fast friends and swimming partners, and eventually Nick became an integral part of how the album came to be. We swam in a lake together every day and would talk about everything from philosophy to music, politics, literature, and what we were working on as the seasons changed around us.

These are some of my happiest memories. If Nick hadn’t insisted under the moon on a dark New Year’s Day swim that I “get on with” the new album — just as he was starting his [Wild God will be released August 30] — I would never have been on a plane to LA three weeks later to record it. Mike Garson wrote the arrangement of Nick’s “Push the Sky Away” as a thank-you to Nick, and it became the centerpiece.

twi-ny: I’m glad you brought that up. How does a classical pianist end up recording one album with Russ Titelman, who has worked with Randy Newman, Rickie Lee Jones, James Taylor, the Monkees, and Eric Clapton, and then Garson, who’s produced and played with the Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails, and, primarily, David Bowie?

hs: I have been in New York for fifteen years now and over that time have had so many adventures, many of which were not directly related to classical music. Russ and I met at Barney Greengrass on the Upper West Side through our mutual friend, author Julian Tepper. Russ wrote his number on a Barney receipt and we would meet for milkshakes. Two years later we were on a train to Pleasantville to “try out” recording together, which then turned into Heaven and Hell: The Doors of Perception, recorded at Samurai NYC.

Russ invited Marianne Faithfull because of my love of William Blake — I recently wrote the lead editorial article for The Journal of the Blake Society, “Invisible Women in Blakean Mythology” — and really the point of the record was just that, to bring together the worlds of rock and roll, literature, classical, and popular music, to see all of them in each other and to have as Blake would have referred to it an “illuminated” experience. Living on Mars continues this threading of the worlds together, just a little more literally.

[ed. note: Stubbs also participated in a January 2022 panel discussion at the Global Blake conference that you can watch here. Faithfull narrates Blake text over John Adams’s “Phrygian Gates” to open Heaven and Hell: The Doors of Perception.]

twi-ny: There are Blakean influences throughout Bowie’s work, particularly in the 1970s. What makes his music so translatable to classical?

hs: I have always been a Bowie fan, and over the years there have been many ways in which our worlds seemed to collide serendipitously. I loved Bowie as a teenager and through my friendship with May Pang became friends with [producer] Tony Visconti and later Mike Garson, who produced and arranged Living on Mars. Before the Bell Canyon wildfires I went to Mike’s home there and played for him, and we started to conceive of the album. We finally got to record it in 2023 in LA, entirely live, which was a thrilling experience.

twi-ny: Who are your favorite classical composers?

hs: It depends who I am at any given time of the day but usually somewhere between late Beethoven’s final piano sonatas living on the border between life and death or dancing through some gothic Prokofiev.

twi-ny: Besides Bowie and Cave, what other contemporary performers or songwriters do you listen to? Who’s doing things that you find musically intriguing?

hs: I have recently started listening to the Last Dinner Party. My rotation at the moment seems to be some [Krystian] Zimerman Brahms B flat piano concerto, the Magnetic Fields, [Marc-André] Hamelin’s late Busoni, Rob Zombie, Judas Priest, Alter Bridge, and the National, but that’s just this week. Always a mix!

twi-ny: Yes, that is quite a mix. Having performed on both sides of the Atlantic for years, do you notice any difference between American and British or European concertgoers, especially over time, pre- and postpandemic?

hs: I think that location is becoming less relevant to those that consume their music entirely through platforms such as TikTok. I think that the US has been more open to contemporary reimagining of classical music than other locations around the world, but social media has changed that concentration, as has the growing need for audience development. Anywhere that there is a live, enthusiastic audience is the same thrill, but there’s nothing like playing to my adopted hometown of New York; it’s electrifying.

twi-ny: You’ll be in New York on June 2 at Joe’s Pub. Have you ever been there before?

hs: I am so excited to perform at Joe’s. This will be my first show there and I can’t wait!

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]