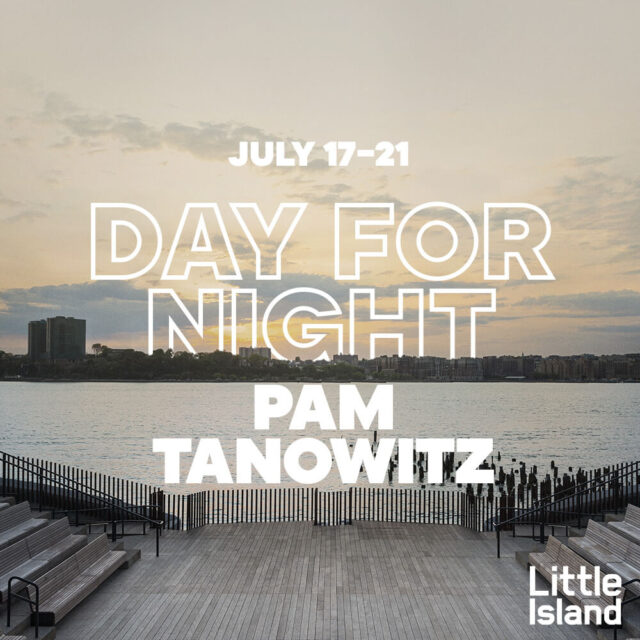

Three-part Day for Night goes from daylight to dusk to evening (photo by Liz Devine)

DAY FOR NIGHT

The Amph at Little Island

Pier 55, Hudson River Park at West Thirteenth St.

July 17-21, $15 standing room, $25 seats sold out, 8:30

littleisland.org

www.pamtanowitzdance.org

Little Island’s inaugural season of site-specific commissions continues with Bronx-born choreographer Pam Tanowitz’s Day for Night, which blends beautifully with the surroundings of the outdoor Amph theater. As the audience makes its way past the grassy green hills that leads to the venue, the dancers are scattered along the path, offering a prologue, clad in diaphanous green costumes. As the audience is being seated in the Amph’s wooden rows, the sun is setting over the Hudson, a golden glow that evokes the title of the show, the term used when a film is shooting a nighttime scene during the day.

The sixty-minute piece was inspired by François Truffaut’s 1973 film, Day for Night, which goes behind the scenes of the making of a movie, featuring a British actress (Jacqueline Bisset) who has recently suffered a nervous breakdown, an aging French star (Jean-Pierre Aumont), an Italian diva (Valentina Cortese), and a young French actor (Jean-Pierre Léaud); Truffaut portrays the harried director.

The dance begins with Lindsey Jones, Marc Crousillat, and Maile Okamura forming an extended pony-stepping trio in which various emotions boil to the surface, including jealousy, power, and revenge. They are later joined by Morgan Amirah and Brian Lawson, who peer out over the river, in addition to Sarah Elizabeth Miele and Victor Lozano. In all black, Melissa Toogood delivers an impressive solo, looking serious and concerned.

The dancers move up the aisles, climb to a pair of scaffold balconies, and rest on the first row of benches, which is covered in fake green grass. They jump, run around in a circle, and lie down on the empty stage. The soundtrack features gentle tones as well as harsher drones, accompanied by recordings of the natural environment of Little Island, from birds and wind to lapping waves, human murmurings, and traffic. When the BBC’s Shipping Forecast plays over the sound system, I initially thought it was coming from a boat passing in the distance. (The immersive sound and music are by Justin Ellington.)

Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung’s costumes come in multiple colors echoing the environs, with loose-fitting tops and tighter bottoms; old-fashioned striped swimming trunks provide contrast to the vertical picket fence bordering the water. Lighting designer Davison Scandrett blasts out red, orange, yellow, blue, green, and almost blinding white.

Tanowitz, who has previously choreographed such works as I Was Waiting for the Echo of a Better Day, Law of Mosaics, and Four Quartets, for such companies as New York City Ballet, the Royal Ballet, Martha Graham, Paul Taylor, Ballet Austin, and her own Pam Tanowitz Dance, teases the audience with a series of false endings and bows before everyone moves over to the Glade, where Toogood, in silver sequins, dances a forceful epilogue to Caroline Shaw and Sö Percussion’s slow, elegiac cover of ABBA’s “Lay All Your Love on Me,” in which Shaw nearly whispers, “Don’t go wasting your emotion / Lay all your love on me / Don’t go sharing your devotion / Lay all your love on me.”

“Cinema is king!” Truffaut’s character says in Day for Night. On Little Island right now, it’s dance that rules.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]