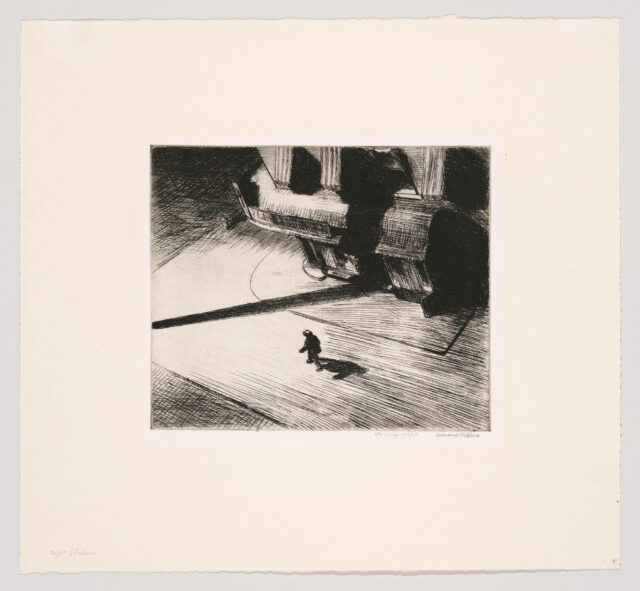

Mitchell Winter is the wolf operating a young boy in Wolf Play (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

WOLF PLAY

Susan & Ronald Frankel Theater, the Robert W. Wilson MCC Theater Space

511 West 52nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through April 2, $68-$88

mcctheater.org

Hansol Jung’s Wolf Play is the most exhilarating hundred minutes you will spend in a theater right now, or at least through April 2, when its extended run at MCC’s Susan & Ronald Frankel Theater concludes.

Originally presented a year ago at Soho Rep in conjunction with Ma-Yi Theater Company, the production has transferred uptown to Hell’s Kitchen with all its joys, and all its horrors, fully intact, with the same cast and crew. Be sure to arrive early to check out You-Shin Chen’s set, which features a prop wall with hundreds of items, from baseballs, dolls, lights, and cabinets to an old stove, luggage, hat boxes, and a cast iron tub. Numerous items are used in the play, while others tantalizingly remain in place; they were carefully selected by director Dustin Wills and propmaster Patricia Marjorie from Wills’s personal collection or from previous shows of his, including a teddy bear, a pirate flag, two cacti, a wooden table with googly eyes, and an image of dancing Russian ladies, as detailed in a lobby display. It gives the show a homey feel; these things could be in anyone’s garage or attic, family mementos as well as junk.

While the house lights are still on, Mitchell Winter emerges from a surprise entrance and offers a prologue, speaking directly to the audience, which is seated on two opposite sides of the space, partially separated by a curtain. “What if I said I am not what you think you see,” he announces. He invites us to imagine that we are in a forest near a river, then tells specific audience members that they are a spider, or an eagle, or a drop of dew, riding on a giant turtle, before pulling the proverbial rug out from under us.

“The truth is a wobbly thing,” he says. “We shall wobble through our own set of truths like jello on a freight train, and tonight I add a bump to that journey and put to you my truth: I am not what you think you see. I am the wolf.” He then lets out a pair of howls and points out, “Wolves get a bad rep for being evil. . . . But you gotta understand these evil wolves are abandoned wolves. Solo wolves, not necessarily out on the prowl to steal your red riding hoods.” Just prior to becoming involved in the narrative, he tells us, “See, wolves suck at being alone. Wolves need family.” And it’s family the wolf will have, but not of its choosing.

The story begins as Peter (Christopher Bannow) arrives at the home of Robin (Nicole Villamil) and Ash (Esco Jouléy) to sell his adopted child. Ash isn’t there, but Robin’s brother, Ryan (Brian Quijada), is. Ash is Robin’s wife, a nonbinary person of color who is not in favor of the whole arrangement. Robin found out about Peter’s son, and how to acquire him, through a Yahoo! online group devoted to the exchange of adopted children; for a relatively small cash payment, Peter will sign over power of attorney to Robin and the deal will be done.

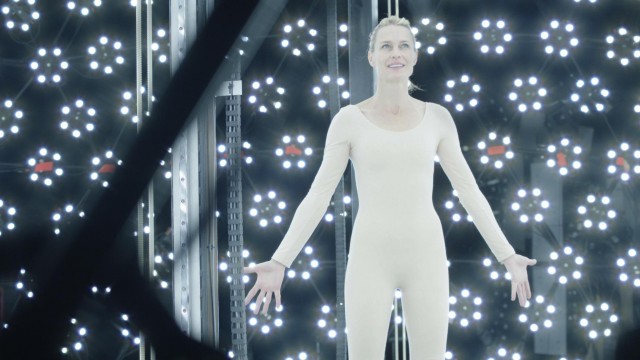

Ash (Esco Jouléy) sits down to breakfast with Jeenu and the wolf (Michael Winter) in Hansol Jung’s Wolf Play (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

Peter is giving up Peter Jr., a Korean orphan whom he and his wife adopted several years earlier, because they have just had a baby of their own and believe they can no longer properly take care of both of them. Peter makes clear to Robin that the child is nonreturnable; she must sign an “affidavit of waiver of interest in child.” Peter insists, “We’re really not terrible people. We really want what’s best for him. We love him. So much. We do.”

The powerful scene also introduces us to the show’s unique conceit: The child, who is six, is a three-foot-tall wooden puppet operated by Winter, who interjects asides to the audience, as if in a PBS nature special. When Peter says, “Katie and I, we had such a great time together, as a family,” the wolf tells us, “Sometimes wolves will ally with another species for coexistence. Wolves are not above making friends if it means survival.” When Peter Jr. won’t let go of Peter’s leg, the wolf explains, “Wolves are an extremely adaptable species / wolf is one of the few that survived the last ice age.”

When the child announces that his name is actually Jeenu and becomes more attached to Ash than to Robin, things get even more complicated. Ash is a boxer preparing for their first professional bout, being trained by Ryan at the gym he runs. They want to concentrate on the match, not raising a kid. As the fight approaches, Peter starts contacting Ryan to find out how things are going with Jeenu, perhaps reconsidering what he has done.

There is nothing conventional about Wolf Play. Jung (Wild Goose Dreams, Cardboard Piano, Human Resources) and Wills (Montag, Plano) inject every action with something unusual and special, and not just for effect, as each detail enhances the development of the story and the characters. The movement, accompanied by Barbara Samuels’s lighting and Kate Marvin’s sound, is spectacularly choreographed with split-second precision and more than a bit of stage magic, as Winter reveals. On several occasions, Ryan is engaged in a phone conversation but his words also seem to be responses to another character doing something else; for example, when Peter, at the sink in his kitchen, asks his unseen wife, “Honey, do you have the email, of those people that you found?,” Ryan, on the phone with his mother, says, “There was no time to ask, the kid was crying like a siren,” as if answering Peter.

One constant on the set is a ramshackle door that is moved around depending on whether it is for Robin and Ash’s home, Ryan’s gym, or another location, but it also represents the different types of entry and exit that are elusive to children such as Jeenu. He’s not a puppet just because it’s cool to watch; he’s treated like an object, similar to the items in the prop wall except more foreign. Early on, after being chastised by Peter for cursing, Ash argues, “We can import him from Asia, we can put him up for auction the minute something doesn’t feel right, but hey now be careful of the f word coz that will really fuck him up.” Shockingly, Wolf Play is not complete fiction; Jung began writing it after reading Megan Twohey’s 2013 Reuters investigative report “The Child Exchange: Inside America’s Underground Market for Adopted Children,” parts of which the audience can read on boards on their way out.

Peter (Christopher Bannow) tries to explain himself in Wolf Play (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

Winter (Frontières Sans Frontieres, Jung’s Romeo and Juliet) is remarkable as the wolf, bringing to life a wooden, thin-limbed puppet, imbuing it with emotion even though it has two black dots for eyes and no mouth, a performance reminiscent of how beautifully Kennedy Kanagawa operated Milky White in the recent Broadway revival of Into the Woods. Especially touching are breakfast scenes in which Ash and Jeenu bond at a long table.

Jouléy (The Demise, Interstate) and Villamil (How to Load a Musket, Network, Lessons in Survival) capture the fears and worries of a young couple suddenly faced with parenthood, while Quijada (Jung’s No More Sad Things, Oedipus El Rey) is the concerned uncle trying to find his place in this new situation. Bannow (Alamat, Oklahoma!) brings humanity to Peter, who could have been a straightforward villain, his name evoking Sergei Prokofiev’s 1936 symphonic fairy tale Peter and the Wolf.

Hovering over all the laughs and all the sighs is the very real issue of child trafficking, particularly of foreign-born children, recalling slavery as well as the current immigration crisis. Wolf Play is an endlessly imaginative and entertaining show, but it is also a cleverly layered examination of systemic problems that continue to haunt America.