Hope Boykin makes her Joyce debut with States of Hope (photo courtesy HopeBoykinDance)

STATES OF HOPE

The Joyce Theater

175 Eighth Ave. at 19th St.

October 17-22 (Curtain Chat October 18), $52-$72

212-691-9740

www.joyce.org

www.hopeboykindance.com

“You have the best day ever,” Hope Boykin told me at the end of our lively Zoom conversation a few weeks ago. And I set out to do just that, as it’s impossible not to be affected by her infectious positivity, encased in a warming glow.

A self-described educator, creator, mover, and motivator who “firmly believes there are no limits,” the Durham-born, New York–based Boykin began dancing when she was four and went on to become an original member of Dwight Rhoden and Desmond Richardson’s Complexions, performed and choreographed with Joan Myers Brown’s Philadanco!, then spent twenty years with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, first under Judith Jamison, then Robert Battle. A two-time Bessie winner and Emmy nominee, Boykin was busy during the pandemic lockdown, performing the “This Little Light of Mine” excerpt from Matthew Rushing’s 2014 Odetta for the December 2020 Ailey Forward Virtual Season, making several dance films, collaborating with BalletX and others, and preparing October 2021’s . . . an evening of HOPE, a deeply personal hybrid program at the 92nd St. Y that investigated Boykin’s truth and her unique movement language.

Next up for Boykin is another intimate presentation, States of Hope, running October 17–22 at the Joyce. Boykin wrote, directed, and choreographed what she calls her “dance memoir,” which features an original score by jazz percussionist Ali Jackson, lighting and set design by Al Crawford, and costumes by Boykin and Corin Wright. The work, in which she explores different parts of herself, will be performed by Boykin as the Narrator, Davon Rashawn Farmer as the Convinced, Jessica Amber Pinkett as the Determined, Lauren Rothert as the Conformist, Bahiyah Hibah Sayyed or Nina Gumbs as the Daughter of Job, Fana Minea Tesfagiorgis or Amina Lydia Vargas as the Cynical, Martina Viadana as the Angry, and Terri Ayanna Wright as the Worried.

On a Wednesday morning, Boykin, evocatively gesticulating with her hands and smiling and laughing often, discussed transitioning from dancer to choreographer, making dance films, seeing Purlie Victorious on Broadway, avoiding ditches, and seeking radical love in this wide-ranging twi-ny talk.

twi-ny: You are in rehearsals for your Joyce show. Where are you right now?

hope boykin: I’m at the 92nd Street Y. I got here early because I was a fellow for the Center for Ballet and the Arts [at NYU] for 2022–23, and then they extended it through the academic year, then they extended it through the summer, but they have new fellows now. And so I will never take an office space and stairs down to the studio for granted again.

Now that I’m a New Yorker, I can say I was schlepping all of the cameras and the computers and the music, and so I found a corner here in the newly renovated Arnhold Dance Center. I give everybody a warmup at 10:15 before we get started. So I’m here early.

twi-ny: I’ve previously interviewed Matthew Rushing and Jamar Roberts, who are two other longtime Alvin Ailey dancers who became choreographers for Ailey while they were still dancing with the company. When you started at Ailey, did you anticipate becoming a choreographer in the way you have?

hb: I don’t think anything was in the way that I had; I definitely didn’t have that thought. I was always making work because at Philadanco!, Joan Myers Brown put into practice a summer event called Danco on Danco!, and so she allowed dancers in the company to choreograph on other dancers in the company, then in the second company, and there was also an evening that would showcase D/2, the second company. The concert was in a small theater. I mean, she gave us tech time and rehearsal so we could see our work on a stage.

That also happened at Ailey once I got there, but I feel like I was able to really create work there. And then I was also an adjunct professor and did choreography at University of the Arts. And so I was choreographing and then seeing things on stages there. But never would I have thought that I would wake up in the morning and say, This is what I do for a living. I mean, it’s a little bit wild. And then in this stage now, having the opportunity to do things under my own name — having commissions is incredible.

It’s not just satisfying because you’re able to travel, but you’re able to meet people and you’re challenged with different environments, you’re challenged with different artists, different genres of dance, and so that’s wonderful. But having your name on it, being responsible to make sure that everyone’s paid on time, having a physical therapy schedule, will that schedule work with the schedule that I made, it’s a different animal.

twi-ny: In some cases you’re choreographing on friends and colleagues you’ve worked with for years, and in other cases you’re working with completely new teams you’re not as familiar with. Is one harder than the other?

hb: That does get a little bit difficult.

twi-ny: You have to boss friends around sometimes.

hb: Well, yeah. You just have to remind them what you want and that as much as they know you and want the best for you, you may not have the answer for why you’re doing something right away, but they have to trust you. And they do. They ultimately do.

Sometimes, it’s funny; you still have to watch your words when they’re people who you love. I love to talk about the found family. And when you have people who are committed to you and they want the best for you, and they maybe think that their opinion’s going to help . . . what really helps above all is their support, not having to pretend or perform when you’re in front of people who don’t know you. You have to show up. You have to do the smiling thing. I mean, we always have to watch our words, especially now. I’m super conscious of how I speak to other artists, but I feel like I’ve always been conscious of that because of things I didn’t like. So I wanted to be one of those people who could tell you the truth and tell you no and tell you I don’t like that, let’s fix it.

twi-ny: Right. Tell them, “I still love you.”

hb: Exactly, “I still love you.” And so I feel that it’s easier for me. We were away during our technical residency in the Catskills, and I just had a yucky morning, and three of the women who I knew I could cry in front of and that they would pray with me did. We started late that day. I was weeping. I said, “I need some help.” They put their arms around me in a group, and then the day got started after that. It was just heavy times. But when you have people who’ve known you, they can also pick up some of the slack when you don’t feel a hundred percent; they fill in the rest.

twi-ny: In your PBS First Twenty episode Beauty Size & Color, you talk about “renegotiating and forcing a change of narrative,” which relates to something that comes up a lot in your work. You talk about finding your own path, that your path is different from someone else’s path. Are we on the right path as a society?

hb: Yes. It’s so interesting. Lately, especially because I’ve been applying for grants — I don’t mean foundational grants, I mean the creative grants — you are competing against hundreds of applications. You’re lucky if someone recognizes your name; maybe recognizing your name will move you forward, but maybe it also won’t. They’re really just trying to look at the topic. And if my topic of what I want to make is not radical enough, if it is not wild enough, if it is not socially piercing enough, if I’m not saying the words that people want to hear from a huge activist, I mean, I’m not saying that I’m not. I’m just saying if those words aren’t the words people want to hear, then it feels like I’m not in those rooms.

So I want to be clear about that. But it feels like you’re not chosen. And I think that love is the most radical thing we should work on. If we were radical with our love, we wouldn’t watch someone fall and then just look at them. We would pick them up. If we were more radical with our love, we would have compassion for those who didn’t have homes. If we were more radical with our love, we would not necessarily need to walk into a school with some sort of weapon. I’m going to tell you when it changed for me: There was a woman who looked fine. She did not look homeless. She was a young white woman, and she was walking in my neighborhood — I live in Harlem, but it’s gentrified. And then she pulled down her pants to take a wee.

And I said to myself, Excuse me, what are you doing? I didn’t judge; she looked perfectly fine. But at some point she was not able to walk into a place and say, May I use the bathroom?

twi-ny: Or someone said no.

hb: Or someone said no. I checked myself in the moment; instead of me saying, How dare you! I should have said, How could I help you? But please understand. I did not think that first; I thought that third or fourth after all of the other things. But if I were more radical with my love, maybe I would’ve said to her, How can I help you? Is there something I could do? I don’t know what her situation was.

twi-ny: Exactly. You don’t know.

hb: And so I want to speak about this love and trying to understand why I felt the lack and why I felt like I was in constant competition with things that I could not control. There are a lot of things I could control. So once again, let me be clear. I’m not trying to be a hypocrite, but if I’m in competition with you simply because you’re bald — I’m usually bald.

twi-ny: I know, I know.

hb: It’s a little bit long today.

twi-ny: Yeah, mine too. Mine too.

hb: But if that’s the case, I’m in the wrong business. I love to go into new studios and tell people, if it were about being tall and blond with a bun, I would not have been working for over twenty years. But I did. Which means that there is room for me; which means that there’s room for you. Now, it doesn’t feel like a lot of room at the time, but if I can make room, if my path is this wild and then I am able to do this, then that means someone else can come in and then they can, and then we can, and then they can. And then we can.

Even on Broadway right now. I went to see Purlie Victorious.

twi-ny: I saw it last night. Unbelievable.

hb: Unbelievable. I’m sure that they thought that the musical, Purlie, was going to be a better moneymaker. What’s the reasoning behind us not seeing that? Yes, the musical, yay, we’re not cutting it. Yay. We love a musical, song and dance. But that piece of art. That was written, what? More than sixty years ago?

twi-ny: Yes. And it felt like it could have been written yesterday. The friend I went with, she saw the musical with Cleavon Little and Patti Jo. She even brought her program from 1972, and she asked, Why is this a musical? Now that she’s seen the play, it’s like, wow.

hb: Yeah, I’m friends with [Purlie Victorious star] Leslie Odom Jr. And he was like, “You think Ms. Jamison wants to come?” I said, “Yeah.” So I called her and she said, “You mean Purlie? I said, No, I mean Purlie Victorious. She said, “Purlie.” I said, “No, Judy. The prequel.”

twi-ny: And to be that funny sixty years ago about this topic. We laughed our heads off while facing this truth.

hb: It’s unbelievable. All of that to say there is a radicalness that can change our view on what truth is. Do you know what I mean? And I’m not thinking in this log line; I call it my log line. It doesn’t really explain the work, but I say in this evening-length, fully scripted new dance theater work. It’s not new because I’m making something no one has ever seen. It’s new for me. It’s a new way for me to express myself. It’s a new way for me to make work that I feel deserves to be spoken about just because it’s my experience. And once again, here I am trying to broaden a path that I feel like other people just need to — I don’t want them to walk the way that I walk. I just want them to feel they’re given the ability to actually walk forward and not feel stunted.

twi-ny: Kara Young, who plays Lutiebelle Gussie Mae Jenkins [in Purlie Victorious], she’s like a dancer at times; she speaks volumes with her body even when not saying anything.

hb: She’s studied and trained in all the disciplines because you can’t move like that, I’m sure, without that agility and understanding. [ed. note: Young studied at the New York Conservatory for Dramatic Arts.] It’s not just being flexible; it’s about awareness. I don’t know all of her story, but I could say I can’t imagine that she didn’t. But I do know that Leslie studied at Danco. That’s where I met him when he was fifteen or sixteen years old. So I know he’s a mover. And his agility — that scene where he kept running back to the window, oh my God. Oh my. The timing. I was like, look at my friend. But anyway.

[ed. note: . . . an evening of HOPE opened with Deidre Rogan dancing to Odom’s rendition of “Ave Maria.”]

twi-ny: One of the things you say is your journey is yours, and your journey is yours. We’re not all on the same journey, even if we’re spending an hour and a half or two hours together in a safe space. Your recent work, first with . . . an evening of HOPE, a beautiful and fascinating thing to experience, and now with States of Hope, is very personal. It can’t get much more personal. You’ve taken this other meaning of your name — the work is very much about moving forward, evolving; hope is an essential theme. And now you’re baring your soul out there. Every choreographer and dancer puts themselves into it, but you’re putting Hope Boykin into it. Is that difficult to do?

hb: It is and it isn’t. Sometimes people are like, “Oh, it must be very healing.” And I was actually having to hear it every day. Getting it out was the part that was the healing part’ hearing other people voice these things has become something a little bit different. Matthew Rushing came to Bryant Park to see me perform a solo. The year before I was rained out; everyone was able to perform except for me. It started raining more. So then the next year, I was just going to do the same work, but no one was available. So I ended up dancing it; I did a recorded voiceover, and then I performed. He was like, “Wow, you really laid it out there. You all right?”

Because not only was it my voice, but you were watching me and hearing my voice. That was sort of the turning point for me. I had taken this memoir writing class during the pandemic here at the 92nd St. Y. And that was also another way that I understood that I could tell my story differently, that I could use prose as well as those poetic sounds. I call them my poetic moments. But I could speak. And I said, Well, what if I turned this around? I was acquainted with Mahogany L. Browne, and I was telling her I wanted to work on this project. And she was like, “Oh, sure, I can help you.” And so she’s called herself my script midwife, and she basically said, “Give me your text.” And she said, amongst other exercises and examinations, “How do you feel about this from this person’s perspective? Write this from your mother’s perspective.”

So then she is teaching me how to take a situation and bring it in together so that these perspectives can have a conversation. Then we named the people, and then the people got ideas. And then instead of them actually having names —because at first I thought they might have names; I just thought that we would hear their characteristic in their name. And she’s like, “Are you sure?” I’m like, “Yeah, I think this is the best way.” And then all of a sudden I was able to have one of them speak to the other. But that’s exactly what’s going on in my mind. Should I buy that purse? It’s pretty expensive. Well, did you pay the rent? Yes, I paid the rent. That’s the logical person. Well, did you buy groceries? Yeah, I bought groceries, dah, dah, dah. But you have that bag. You have another bag that looks just like that bag. So all of these ideas are floating around. Well, should you get it? Because if you just save that money, maybe you could put that money away. That’s the worry. You know what I mean? Maybe you could put that money someplace else. And then the Angry says, of course I buy the bag. I’m worth it. I want to buy it. And so all of these ideas — I’m not going to say people, but these states, these parts, these slivers of me are living together.

twi-ny: You’re talking about the Determined, the Conformist, the Cynical, the Convinced, the Angry, the Daughter of Job, and the Worried.

hb: And the Worried. Yes.

twi-ny: All parts of you and parts of other people in your life.

hb: Yes. Parts of me hearing other people. There are parts of me, but they also represent experiences that I’ve had. Matthew, when he was creating Odetta, he told the whole cast, “The turning point for me being able to make this piece was realizing that all of the people and all of my influences were inside of me, that they’re all an ingredient. And so there’s no point in trying to pretend that this doesn’t have some Ailey in it. It doesn’t have some Judy in it. It doesn’t have some [Ulysses] Dove.”

[ed. note: Boykin performed the “This Little Light of Mine” excerpt from Odetta for the December 2020 Ailey Forward Virtual Season.]

He said, “I’d be ridiculous to think that all of those influences weren’t coming out of me.” Because we’re always trying to do something brand new, right? But there’s nothing new under the sun. So we have to just know that all of those people are a part of me. So when my mother makes a statement to me, I make that statement to another person, who’s younger, because I learned that lesson. If I fall in the ditch — I’m from North Carolina; we had ditches. So if I fall in the ditch —

twi-ny: We have potholes here.

hb: Right? But if I can tell someone, “Hey, there’s a ditch about three feet from there, just go around it,” and they don’t listen, then they’re like, “Hope told me about that ditch.” It won’t be, “I didn’t know there was a ditch there.” And so all of those people have played a part of who those characters turn out to be and will be. It’s interesting, and it’s challenging, but I want to do it. I feel it’s important.

twi-ny: I’m looking at the seven characters, and I guess you’re the eighth.

hb: Oh, yeah.

twi-ny: All of us fit into every one of those characters. I was even thinking about the Book of Job the other day. So, in choosing the dancers, did you have ideas for who you wanted for each part? Did you have auditions, or did you say, Oh, I already know who’s going to be doing this and who’s doing that?

hb: There were a few people that I knew I wanted. There was all dance first. There were people who I know dance and then act; one of the dancers is on Broadway right now. Some of them have been in movies and television, but I’ve met most everyone through my relationship with the Ailey organization. Two of them are former students of mine from USC. So everything is dance first. And I let people know that we have to read and we have to act. And I let them know that I’ll help you do that. Not because I can, because I know people who can.

twi-ny: Well, that’s key.

hb: Yes, it’s key. Yes. And so a couple of the dancers had never read before. So I said, I want you to read this. And then I would say, “No, try reading it with this tone; here’s the back story for that person. Read it like this.” And then once the nerves are gone, and once they understood, all of a sudden the person who can physicalize pain without speaking can now speak pain and physicalize it at the same time, in my opinion, is probably going to be better than the person who has to learn to move. Because we do. We go onstage hungry, experiencing loss. I’ve danced directly after my father’s funeral. There’s just this thing. We are just experiencing things, but we don’t get to say it. So imagine if I can scream, “I’m still angry! I’m still angry!”

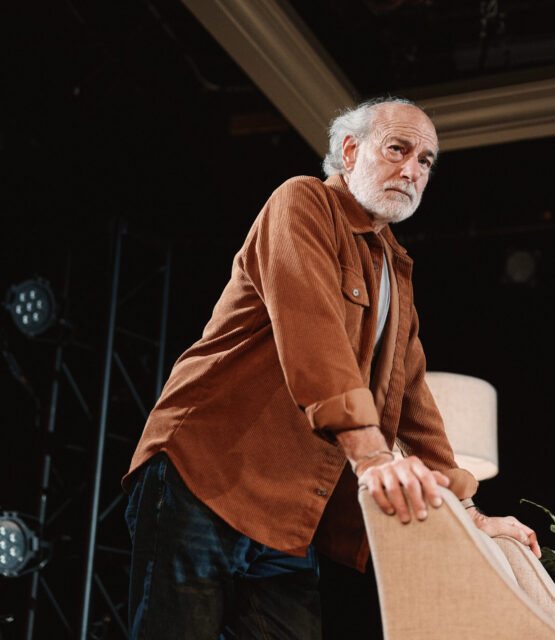

Hope Boykin will get personal in States of Hope at the Joyce (photo courtesy HopeBoykinDance)

Watching them do that is just amazing. The sweetness of Daughter of Job says, “Well, are you sure this is the way you want to move?” And then Cynical says, “Well, I don’t know.” So it wasn’t an audition per se, but some of them I needed to let them know, “I do need you to read this. I need to understand.” But I think it’s perfectly cast. I think there are challenges to everyone’s level. Another friend of mine said to me, “You realize that actors ask why. And dancers say okay.” So now I have to have these dancers ask me why all the time. And I’m like, “Can you just try it?”

twi-ny: At the Joyce, of all places. This is the big time for them, for all of you.

hb: It’s a big time for me. And I am excited and nervous, but it’s successful already because of the people in the room. It’s successful because they’ve already not just agreed but taken on the weight of this work in a way that is just — I’m just really blessed.

twi-ny: It’s got to be so gratifying for you.

hb: Yes.

twi-ny: You have said, “I’ve waited, sometimes patiently, for my turn, permission to be given. Who have I been waiting on and why? I can’t wait anymore.” What’s the next, as you call it, “hope thing” after the Joyce?

hb: I have some projects that are simmering, and they’re the ones that you can’t forget about, the ones you don’t need to write down, the ones that you are, like, Oh, I can see this happening.

You mentioned Beauty Size & Color. Three of the four cameras that were used to film that I own, the microphones are mine, the lights are mine. I mean, of course I had support from the spaces that we were in, but there’s something about being behind the camera that is so thrilling, because as a person who moves bodies in space, I see dance on film in a way that is scripted, much like what I’m working on right now with States of Hope.

So that’s just me dropping a little bit of some simmering plans, a scripted dance film that is moving while speaking. It’s not just moving instead of the word, but they’re working in tandem, which is why this States of Hope process feels difficult because everyone has to learn their lines, then you block them in the space. Or we work with choreography in the morning, and then I say, Oh, we’re going to do this choreography with this scene. And at first it’s like, Well, I can’t say that and do that. And then it’s like, Oh, okay, maybe I could say that and do that. Well, you know what? Then all of a sudden they’re literally moving and speaking at the same time. So the layers upon layers upon layers of trying to add to this presentation is what the challenge has been. But I’m happy right now. I don’t think it’ll be complete. I don’t think it’ll be finished by October 17. I think that I will still have to add and see things that I was like, Oh, I should have done that. But I have time.

twi-ny: So you’re still a little worried, who is one of the characters, and you’re happy, who is not. The happy person is not one of the people. But you’re not angry either.

hb: I’m not angry. [laughs] No, I’m not angry.

[Mark Rifkin, who wants you to have the best day ever, is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]