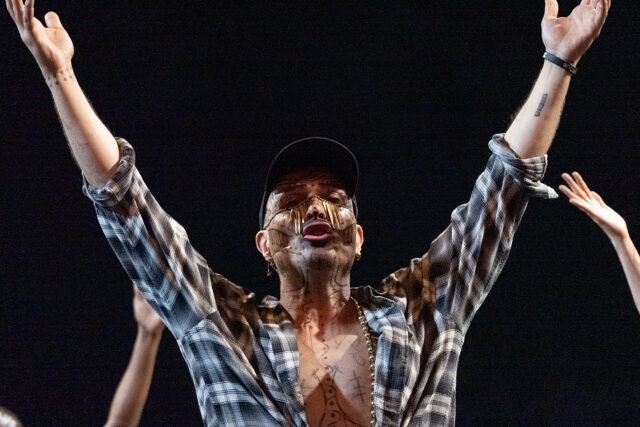

Close friends Michael Shannon and Paul Sparks star in TFANA adaptation of Waiting for Godot (photo by Hollis King)

WAITING FOR GODOT

Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center

262 Ashland Pl. between Lafayette Ave. & Fulton St.

Tuesday – Sunday through December 23, $97-$132

866-811-4111

www.tfana.org

On the 1985 Talking Heads song “Road to Nowhere,” David Byrne sings, “Well, we know where we’re goin’ / But we don’t know where we’ve been / And we know what we’re knowin’ / But we can’t say what we’ve seen / And we’re not little children / And we know what we want / And the future is certain / Give us time to work it out.”

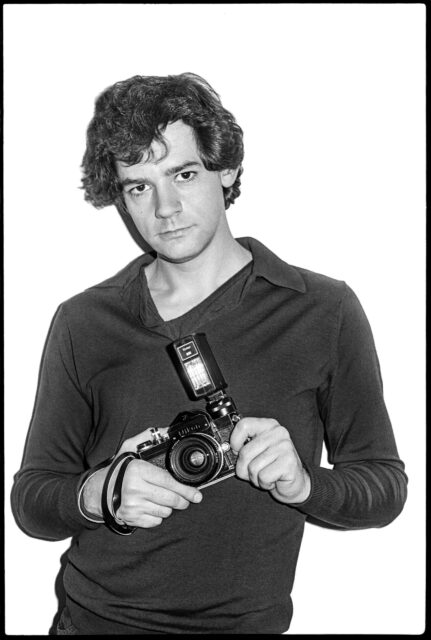

I was thinking about that song while watching Arin Arbus’s spirited adaptation of Samuel Beckett’s absurdist Waiting for Godot at Theatre for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center in Brooklyn. Riccardo Hernandez’s set is a long, narrow, dusty platform that bisects the seating from the back of the theater all the way to where the proscenium stage would have been, which now leads into a dark void. Two yellow traffic lines run down the middle, making the set a postapocalyptic road to nowhere.

The orchestra features three rows of seats on either side of the abandoned thoroughfare, while the mezzanine and balcony have chairs on three sides. As the crowd enters, Estragon, aka Gogo (Michael Shannon), is sitting on a rock, deep in thought, or as deep in thought as he can get. Opposite him is a bare tree. After several minutes, he tries to take off one of his boots, with no success. “Nothing to be done,” he says as Vladimir, aka Didi (Paul Sparks), joins him.

Through nearly the entire 145-minute show (including intermission), Didi doesn’t step on the yellow lines, nimbly leaping over them or walking or standing right next to them. Sparks is a marvel to watch as he avoids the lines often without looking down at them, as if via muscle memory or like they are emitting some kind of negative energy. Meanwhile, Gogo doesn’t even seem to notice the lines, dragging his feet, either bare or in wretched shoes (go-go boots?), striding on them as if they’re not there.

The yellow lines, and the two protagonists’ different interaction with them, amplify the duality inherent in the play in a way that I have to admit has never stood out to me before, offering fascinating nuance to a work I have now experienced five times in the last nine years, on and off Broadway and online, by Irish, English, American, and Yiddish companies.

Two yellow lines run down the center of the stage at TFANA’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center (photo by Hollis King)

Waiting for Godot unfurls in an unidentified time and place. A pair of disheveled men discuss food, feet, and suicide while waiting for a mysterious figure they’ve never met to arrive, as if he will bring meaning to their lives. “Time has stopped,” Didi says when Pozzo listens to his pocket watch. Pontificating on their situation, Didi says, “We wait. We are bored. [He throws up his hand.] No, don’t protest, we are bored to death, there’s no denying it. Good. A diversion comes along and what do we do? We let it go to waste. Come, let’s go to work! In an instant all will vanish and we’ll be alone once more, in the midst of nothingness!”

In each act a carnivalesque man named Pozzo (Ajay Naidu) and his servant, Lucky (Jeff Biehl), pass through, the former snapping his whip, the latter carrying a suitcase and a picnic basket and tied to a rope like a horse. In addition, a young boy (Toussaint Francois Battiste) shows up with important information at the end of each act.

There are two of nearly everything in the play: Vladimir’s and Estragon’s nicknames are doubled: Didi and Gogo. There are two yellow lines down the road, dividing it into two geographic sections. There are two acts over two days, with no past and no future. Didi and Gogo are two friends who seem to be unable to exist without each other, no matter how hard they might try. Pozzo and Lucky are physically connected by the rope. Lighting his second pipe, Pozzo enthuses, “The second is never so sweet . . . as the first I mean. But it’s sweet just the same.”

There are only two props, the rock and the tree. After intermission, there are two green leaves on the tree. The boy, who is solo, speaks of his abused brother, as if his sibling might be a doppelganger.

Even actors Shannon and Sparks are like their own duo; they are close personal friends who brought the show to TFANA as a unit. They have previously performed together onstage — including in The Killer at the Polonsky — and in movies and on television.

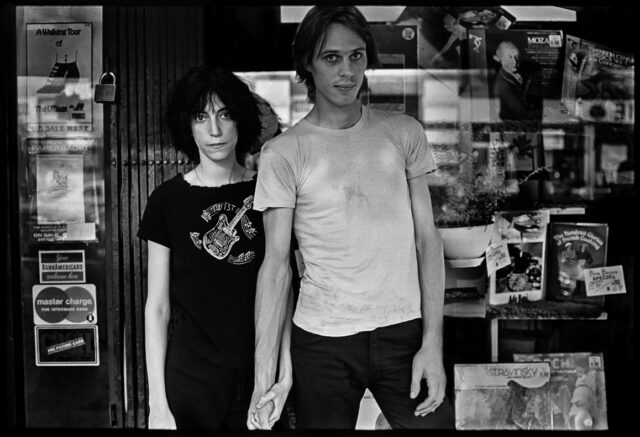

Didi (Paul Sparks) and Gogo (Michael Shannon) juggle hats in Waiting for Godot (photo by Hollis King)

Fortunately, Arbus (Des Moines and Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, both with Shannon) does not get bogged down by the doubling. This Godot (accent on the first syllable) is loud and aggressive, with less of the kind of vaudeville shtick that many productions revel in. The characters don’t wear the traditional bowlers; when Didi and Gogo swap their hats and Lucky’s, it is not merely a funny skit but refers to the interchangeability of people, as Didi suggests that he can take over for Pozzo and Gogo can be Lucky. In addition, just as the boy does not get beaten but his brother does, Gogo gets roughed up every night but Didi wakes up unharmed.

The dichotomy also relates to the two thieves who are crucified with Jesus; Didi points out how only one of the four evangelists wrote that one thief was saved, evoking Didi and Gogo’s potential fate while they wait for Godot. Perhaps the double yellow lines are a kind of cross, which could explain in part why Didi avoids touching it out of fear of damnation.

“The road is free to all,” Pozzo says. Didi responds, “That’s how we looked at it,” to which Pozzo replies, “It’s a disgrace. But there you are.” Gogo concludes, “Nothing we can do about it.”

Shannon’s (Grace, Long Day’s Journey into Night) Gogo is bleak and downtrodden, shoulders hunched, while Sparks’s (Grey House, Edward Albee’s At Home at the Zoo) Didi is mischievous and hopeful. Whenever Didi is asked what they’re doing, Sparks spits out “Waiting for Godot” like the words don’t matter. At one point they even sit together in the audience, fully enjoying themselves.

Naidu (The Master and Margarita, The Kid Stays in the Picture) is boisterous as Pozzo, while Biehl (The Merchant of Venice, Life Sucks.) beautifully morphs from his stiff, silent servant to deliver Lucky’s long, complex monologue about tennis, quaquaquaqua, the divine, and nothingness. Battiste (A Raisin in the Sun) does a fine job as the boy, who offers a promise that might never come to fruition.

Susan Hilferty’s costumes turn the raggedy Didi and Gogo into hobos, although there is no boxcar to come and whisk them away. Chris Akerlind’s lighting takes the scenes from night to day with a nearly blinding, heavenly blast, while Palmer Hefferan’s sound maintains the feeling of being lost. The choreography, primarily Lucky’s dance, is by Byron Easley. Beckett expert Bill Irwin, who has portrayed Didi and Lucky, serves as creative consultant.

“That passed the time,” Didi says at one point. Gogo quickly replies, “It would have passed in any case.” Didi responds, “Yes, but not so rapidly.”

And so goes another Godot, a lovely way to pass the time while asking, but never answering, two of life’s biggest questions: Who are we, and what are we waiting for?

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]