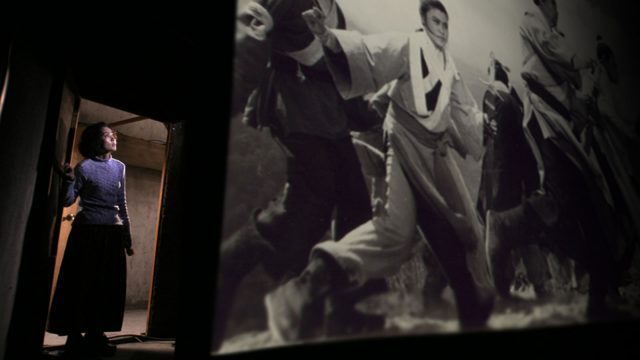

Get tickets to such shows as Volcano at the Under the Radar festival before time runs out (photo by Emijlia Jefrehmova)

UNDER THE RADAR 2024

Multiple venues

January 5-21

utrfest.org

There was quite an uproar in June when Public Theater artistic director Oskar Eustis announced the cancellation of the widely popular Under the Radar festival, which the Public had hosted since 2006. Held every January, the series featured a diverse collection of unique and unusual international theatrical productions, discussions, and live music and dance, from the strange to the familiar, the offbeat to the downright impossible to describe. Eustis followed that outcry with another message:

“Last week, difficult news was shared that the Under the Radar festival would not return for the Public’s 23–24 season. We made the painful decision to place the festival on hiatus. I understand and share the hurt that those who participated in and loved the festival have expressed over the past few days. . . . Unfortunately, these are exceptionally challenging times in our field. The Public, like almost every other nonprofit theater in the country, is facing serious financial pressure. . . . In the certainty that better times will come, we continue to work to preserve the health and mission of the Public. We look forward to a time when we can fully expand back into the robust and expansive theater we need to be.”

Festival founder and director Mark Russell was determined that the show must go on, and he brought it back to life. “Festivals are celebrations. They mark harvests and other moments of abundance or recognition,” he said in a statement. “Under the Radar is a festival that each year celebrates the vibrancy of new theater, in New York and internationally. At this moment, even in very challenging times, there is still innovative work rising from communities around New York and in far-reaching parts of the globe. Under the Radar aims to spotlight this work for audiences — not only those ‘in the know’ but from a wider stretch of communities, diverse in all respects, that could benefit by engaging with these creative leaders.”

The 2024 program includes two dozen presentations at seventeen venues, taking place from January 5 to 21. Below are my top five choices, which do not include two highly praised and strongly recommended works that are making encore appearances in New York, Dmitry Krimov/Krymov Lab NYC’s Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin: In Our Own Words at BRIC and Shayok Misha Chowdhury’s bilingual Public Obscenities at Theatre for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center. In addition, the UFO sidebar of works in progress consist of Matt Romein’s Bag of Worms at Onassis ONX Studio, Zora Howard’s The Master’s Tools at Chelsea Factory (with Okwui Okpokwasili as Tituba from The Crucible), Holland Andrews and yuniya edi kwon’s How does it feel to look at nothing at National Sawdust, Theater in Quarantine and Sinking Ship Productions’ live debut of the previously streamed The 7th Voyage of Egon Tichy at the Connelly Theater, Jenn Kidwell and *the Blackening’s We Come to Collect [A Flirtation, with Capitalism] at the Flea, and Penny Arcade’s The Art of Becoming — Episode 3: Superstar Interrupted [1967-1973] at Joe’s Pub. In addition, a free symposium at NYU Skirball Center on January 12 at 9:30 am features Inge Ceustermans, Hana Sharif, Sunny Jain, Taylor Mac, Jeremy O. Harris, Ravi Jain, and Kaneza Schaal, hosted by Edgar Miramontes, looking at the future of independent theater.

A book club offers unique insight into Miranda July’s The First Bad Man (photo by Ros Kavanagh)

THE FIRST BAD MAN

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

Samuel Rehearsal Studio, 70 Lincoln Center Plaza

January 5-13, choose-what-you-pay (suggested admission $35)

www.lincolncenter.org

www.panpantheatre.com

Ireland’s Pan Pan Theatre has staged unique versions of Beckett’s Embers and Cascando as well as Gina Moxley’s The Patient Gloria. The company now turns its attention on a unique aspect of literature; for The First Bad Man at Lincoln Center’s Samuel Rehearsal Studio, audience members watch a book club dissect Miranda July’s wildly original 2015 novel, as characters and story lines intersect with reality.

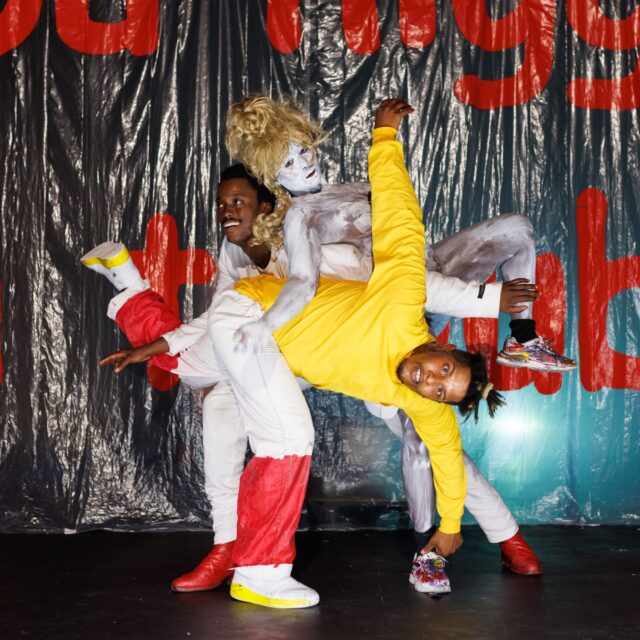

A bouncy castle becomes more than just a fun children’s place in Nile Harris’s this house is not a home (photo by Alex Munro)

this house is not a home

Playhouse at Abrons Arts Center

466 Grand St. at Pitt St.

January 6-14, $30.05

www.abronsartscenter.org

A bouncy castle helps Nile Harris explore how the world has changed over the last two years, with the assistance of Crackhead Barney, Malcolm-x Betts, slowdanger, and GENG PTP along with a gingerbread minstrel, vape addicts, a movie cowboy, and others, in this house is not a home. Afropessimism is on the menu in this collaboration between Abrons Art Center and Ping Chong Company.

Hamlet | Toilet makes its NYC debut at Japan Society (photo courtesy Kaimaku Pennant Race)

HAMLET | TOILET

Japan Society

333 East 47th St. at First Ave.

January 10-13, $35

japansociety.org

In 2019, Yu Murai and Kaimaku Pennant Race blew our minds with the outrageous Ashita no Ma-Joe: Rocky Macbeth, a bizarrely entertaining mashup of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky Balboa. They’re now back with another mad mix at Japan Society; I’m not sure there’s much more to say that what’s in the press release: “Notoriously iconoclastic and scatological director Yu Murai’s Hamlet | Toilet runs the Bard’s highbrow tale of existential woe through the poop chute.” Each ticket comes with free same-day admission to the exhibition “Out of Bounds: Japanese Women Artists in Fluxus.”

VOLCANO

St. Ann’s Warehouse

45 Water St.

January 10-21, $54

stannswarehouse.org

Melding theater, dance, and sci-fi, Irish writer, director, and choreographer Luke Murphy (Slow Tide, Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte) introduces audiences to the mysterious Amber Project in this four-part miniseries of forty-five-minute multimedia segments starring Murphy and Will Thompson, exploring their past as they face an uncertain future.

OUR CLASS

BAM Fisher, Fishman Space

321 Ashland Pl.

January 12 – February 4, $68-$139

www.bam.org

ourclassplay.com

During the pandemic, Igor Golyak and Massachusetts-based Arlekin Players Theatre broke through with innovative, interactive livestreamed productions, attracting such stalwarts as Jessica Hecht and Mikhail Baryshnikov to join the troupe. Following shows at BAC and Lincoln Center, the company brings a timely new adaptation of Tadeusz Słobodzianek’s Our Class to BAM, about a 1941 pogrom in Poland that severely impacts the relationships of a group of students. Broadway veterans Richard Topol, Alexandra Silber, and Gus Birney star, alongside Jewish and non-Jewish cast and crew members from Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Israel, Germany, and the US.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]