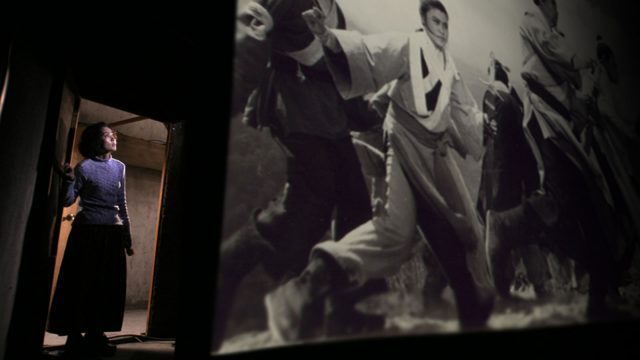

Caroline T. Dartey and James Gilmer team up in world premiere of Elizabeth Roxas-Dobrish’s Me, Myself and You (photo by Paul Kolnik)

ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER

New York City Center

131 West 55th St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Through December 31, $42-$172

www.alvinailey.org

www.nycitycenter.org

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s annual all-new programs at City Center are among my favorite events of the year, and the 2023 edition, the troupe’s sixty-fifth anniversary, is no exception. The evening began with a new production of Alonzo King’s Following the Subtle Current Upstream, which the choreographer calls “a piece about how to return to joy”; the original debuted at City Center in 2000. The twenty-two-minute work unfolds in a series of vignettes featuring, on December 23, Patrick Coker, Isaiah Day, Caroline T. Dartey, Coral Dolphin, Samantha Figgins, Jacquelin Harris, Yannick Lebrun, Corrin Rachelle Mitchell, and Christopher Taylor, who perform to silence, a storm, chiming bells, and other sounds by Indian percussionist Zakir Hussain, American electronics composer Miguel Frasconi, and the late South African singer and activist Miriam Makeba (a gorgeous duet to “Unhome”). At one point a dancer is alone onstage, like a music box ballerina, two horizontal beams of smoky light overhead; the lighting is by Al Crawford based on Axel Morgenthaler’s original design, with tight-fitting, short costumes by Robert Rosenwasser, the men in all black, the women in black and/or yellow.

Former Ailey dancer Elizabeth Roxas-Dobrish’s world premiere, Me, Myself and You, is a seven-minute duet that recalls Jamar Roberts’s 2022 In a Sentimental Mood, about a young couple exploring love and desire. Here Roxas-Dobrish uses Damien Sneed and Brandie Sutton’s version of the Duke Ellington classic, “In a Sentimental Mood,” as Dartey, in a sexy, partially shear black gown, sets up a three-paneled mirror in the corner and shares tender moments with James Gilmer, bare-chested with black pants, combine for some awe-inspiring moves. The costumes are by Dante Baylor, with lighting by Yi-Chung Chen that makes the most of the couple’s reflections in the mirror while calling into question whether it is actually happening or a memory or fantasy.

A new production of Hans van Manen’s Solo, originally performed by the company in 2005 and staged here by Clifton Brown and Rachel Beaujean, is seven minutes of playful one-upmanship as Renaldo Maurice, Christopher Taylor, and Kanji Segawa strut their stuff in a kind of dance-off, their costumes (by Keso Dekker) differentiated by yellow, orange, and red; as each finishes a solo, they make gestures and eye movements inviting the next dancer to top what they have just done. But this is no mere rap battle; instead, it’s set to Sigiswald Kuijken’s versions of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Partita for Solo Violin No. 1 in B minor, BWV 1002 — Double: Presto” and “Partita for Solo Violin No. 1 in B minor, BWV 1002 — Double: Corrente.”

A new production of Ronald K. Brown’s Dancing Spirit honors Judith Jamison’s eightieth birthday (photo by Paul Kolnik)

In 2009, AAADT presented the world premiere of by Ronald K. Brown’s Dancing Spirit, which Brown choreographed as a tribute to former Ailey dancer Judith Jamison’s twentieth anniversary as artistic director of the company. Now, in honor of Jamison’s eightieth birthday, Brown revisits the work in a lovely new production. The half-hour piece, danced by Hannah Alissa Richardson, Deidre Rogan, Yazzmeen Laidler, Harris, Solomon Dumas, Taylor, Christopher R. Wilson, Jau’mair Garland, and Coker, builds at a simmering pace as the cast, in blue and white costumes designed by Omatayo Wunmi Olaiya that evoke Jamison’s performance of the “Wade in the Water” section of Revelations, move in unison and break out into solos, duets, and other groups to Stefon Harris’s and Joe Temperley’s versions of Ellington’s “The Single Petal of a Rose,” Wynton Marsalis’s “What Have You Done?” and “Tsotsobi — The Morning Star (Children),” the Vitamin String Quartet’s cover of Radiohead’s “Everything in Its Right Place,” and War’s “Flying Machine (The Chase).” Brown incorporates Afro-Cuban and Brazilian movement into his rhythmic language; the work is highlighted by Dumas and Richardson celebrating Ailey and Jamison, respectively, with stunning solos as the moon arrives for a glowing conclusion.

Also debuting at City Center in 2023 is a new production of Roberts’s Ode and the world premiere of Amy Hall Garner’s CENTURY.

In her 1993 autobiography, Dancing Spirit, Jamison writes, “Dance is bigger than your physical body. When you extend your arm, it does not stop at the end of your fingers, because you’re dancing bigger than that; you’re dancing spirit.” AAADT has been maintaining that spirit for sixty-five years, with more to come.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]