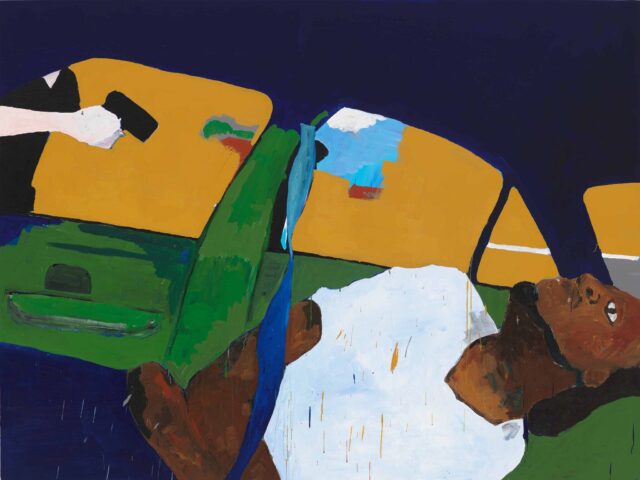

Mai Khôi returns February 1 to Joe’s Pub with the final iteration of Bad Activist (photo by Nate Guidry)

BAD ACTIVIST

Joe’s Pub

425 Lafayette St.

Thursday, February 1, $15-$25 (plus two-drink or one-food-item minimum), 7:00

publictheater.org

mai-khoi.com

Back in September, I attended a friend’s wedding in rural Pennsylvania. Sitting at our table was a woman who was introduced to us as Mai Khôi, the Lady Gaga of Vietnam. We discovered later in the evening why, when, in full makeup and costume, she performed a song written especially for the occasion. The groom, Alex Lough, is an experimental musician and teacher, and the bride, Hanah Davenport, is a singer-songwriter and urban planner; at one point the party broke out into a Greenwich Village–style happening with a series of avant-garde presentations.

Born Đỗ Nguyễn Mai Khôi in 1983 in Cam Ranh, Vietnam, Mai Khôi was an award-winning pop star whose activism infuriated the government as she advocated for freedom of expression, LGBTQ and women’s rights, and the environment and against censorship, domestic violence, and Donald Trump. She also got into trouble by announcing that she did not want to have children.

She’s been playing music since she was six, in her father’s wedding band and later in clubs. She released her first album in 2004, and ten more solo records followed between 2008 and 2018; as her fame and fortune exploded, so did her concern for the welfare of the Vietnamese people. She challenged the police and the government, leading her to have to play secret shows for her fans. Shortly after the release of the 2019 documentary Mai Khôi and the Dissidents, which screened at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival, she fled to America; she currently lives in Pittsburgh with her personal and professional partner, Mark Micchelli.

“Even though Mai Khôi primarily sings in Vietnamese, you can always understand the intention she’s trying to convey,” Lough, who is producing her upcoming album, explained to me. “Her band has a refreshing approach to protest music, like we haven’t heard since Rage Against the Machine. She has an incredible emotional range, from delicate sadness and vulnerability to screaming and extended vocal techniques. She is also able to freely move between her role as the frontwoman to blending in with everyone; it’s rare to see that kind of versatility in a vocalist with such a commanding stage presence.” The record will feature such tracks as “We Never Know,” “Innocent Deer,” and “The Overwhelming Feeling that We’re Already Dead.”

On February 1, she will return to Joe’s Pub with the biographical multimedia Bad Activist, which details her life and career through music, photographs, video, archival footage, and more. Directed by Cynthia Croot, the seventy-five-minute show features such songs as “Reeducation Camp,” “Just Be Patient,” and “Bitches Get Things Done,” with Mai Khôi joined by Alec Zander Redd on saxophones, Eli Namay on bass, PJ Roduta on drums, and music director Micchelli on keyboards, playing a mix of experimental jazz rock, folk, and deliberately cheesy pop; Aaron Henderson is the projection designer. Although the work has been performed and workshopped over the last four years at small venues and universities, this iteration is the debut of the full, finished production.

I recently spoke with Mai Khôi and Micchelli over Zoom, discussing music, repressive governments, cooking, and why she considers herself a bad activist.

twi-ny: The three of us were at the same table at Alex and Hanah’s wedding. How did you first meet Alex?

Mark Micchelli: Alex and I met in September of 2016; we were in the same cohort at the University of California, Irvine, where Alex finished his PhD and where I did my master’s. I moved out east, if you can call Pittsburgh east, first in 2019, and then he moved to South Jersey in 2020. And so we’ve been musical collaborators since 2016 and been around the world. We’ve done gigs throughout California and in Pennsylvania, Florida, Ohio, New Hampshire, and South Korea.

Mai Khôi: In 2020, I got a fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh and I was invited to work with Mark. We began with my project Bad Activist.

mm: I had actually gotten an email from the University of Pittsburgh that said there’s this Vietnamese singer-songwriter who’s looking for a pianist who knows something about jazz and Southeast Asian traditional music. And I said, Well, no one’s qualified for that job, so I may as well try. When I was told that I’d have to learn the music in three weeks, I knew I didn’t have time to learn it in that amount of time. I drafted an email to basically politely decline and say, find another pianist. And then I thought I should actually look up what this person’s music actually sounds like. And now we own a house together.

twi-ny: When was the last time you were in Vietnam to either see family members or play a secret show?

mk: Oh, when I moved to the US at the end of 2019. I have not been able to come back to Vietnam since.

twi-ny: What will happen if you try to go back? Would they arrest you?

mk: Yes, they could arrest me. They could detain me. That’s what happened with an activist friend of mine. So, yeah, it’s still dangerous for me to go back, so I’ve chosen not to. My friend had the same situation, like me. She left Vietnam for two years, and then when her mother got sick, she wanted to come home, but the police arrested her, and she is now in jail. They sentenced her to three years.

twi-ny: What family do you have in Vietnam?

mk: My mother, my father. And I have one brother who lives with them.

twi-ny: If they left the country, say, to visit you here, would they be allowed back in?

mk: They don’t have any plans to leave Vietnam.

twi-ny: But if they did, would the government let them return?

mk: If the police want to arrest you, they can arrest you any time. But I think my family will be safe because they’re not involved in activism at all. They did try to convince me to not get involved. From the beginning, the police came and investigated them. After many visits to my parents’ house, they realized my parents have nothing to do with activism, so they leave them alone.

twi-ny: Are you in contact with them either over the phone or via social media? I know you’ve accused Facebook of being in bed with the Vietnam government.

mk: My parents still use Facebook; that is the main thing we use to see each other every day. Of course, I know the police always follow my Instagram and my Facebook and try to hack into them. But it’s okay. I still know how to use Facebook to spread my word and deal with the situation. Someone like my parents or other friends that are not activists, they will not comment on any sensitive things I post on Facebook. They don’t like some of the posts about politics anyway.

twi-ny: You’ve said, “No one can stop me.” Has the government come to you and said, If you take back some of the things you’ve said, we’ll leave you alone?

mk: They did try that in 2016 [when I was applying to run for the National Assembly]. They sent a person to talk to me to give me that deal. Like if you withdraw your nomination campaign, the system will make you even more famous. That was the deal, but I didn’t take it.

I refuse to talk with them about those kinds of things. When the government detained me a couple of years after, they asked me some questions and I just gave them information that’s already public.

twi-ny: What are some of the main issues you are rallying against, in Vietnam and America?

mk: You will see this when you come to see Bad Activist. I am focusing on freedom of expression. And recently, I’m doing some advocacy work for climate activists. Because I’m here, it’s easy to lobby Congress and the State Department, to work with the US government. [ed. note: Mai Khôi met with members of Congress last summer, before President Biden traveled to Vietnam.]

Also, I was surprised by the brutality of the police here, so I want to fight against that. It’s very similar with the police in Vietnam. In New York, when the Black Lives Matter movement happened, I went to the protest every week. I really feel the brutality of the police everywhere is just the same.

twi-ny: On February 1, you’ll be at Joe’s Pub, where you performed two earlier versions of Bad Activist in 2021–22. What do you think of the venue?

mm: They treat you super well. They know how to work with performers.

mk: In 2020, they started to work with the SHIM:NYC team for artists like me, to give us a chance to perform in an iconic venue in New York like that. [ed. note: SHIM:NYC is “a creative and professional residency and mentorship program for international musicians who are persecuted or censored for their work; are threatened on the basis of their political or religious affiliations, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender identity; have been forcibly displaced; need a respite from dangerous situations; or are from countries experiencing active, violent conflict.”]

mm: We do have City of Asylum in Pittsburgh, which does something similar.

twi-ny: What makes you a bad activist?

mk: There’s some moments that I realized maybe I’m a bad activist because I am first an artist, but because I was born in my country, a country that’s not safe for artists, I decided to become an activist to protect my right to be an artist. So that’s why I don’t have good training to become a good activist. Sometimes I upset people. And sometimes I organize some things that aren’t . . . I just think sometimes I feel I’m a bad activist.

mm: I’ve had a lot of conversations with Khôi about this, and I feel like everyone who sees the show has the opposite feeling of Khôi about her and her activism, but everything she says is genuine. And I think the broader point is that despite her activism and since she has fled to the States, the situation in Vietnam has only been getting worse. And so I think reflecting on that failure is something that the show tries to come to terms with and talk about and that’s why the name is framed that way.

mk: Yes. So the point is, whether you’re bad or you’re good, you at least try to be an activist, to contribute something.

Mai Khôi has been playing music since she was six years old (photo courtesy Mai Khôi)

twi-ny: Activism these days seems to be more dangerous than ever.

mk: I don’t know. I just do things that I feel are the right thing to do and I do them. I always believe that doing the right thing will lead you to something good, even when you have to pay a price for doing it.

twi-ny: What’s next after Bad Activist?

mk: We have some ideas for a new project. It will be based on the activism and culture that I carry from Vietnam to here.

twi-ny: What do you do when you’re not making music or fighting the power?

mk: I have a hobby: cooking.

mm: Khôi is as good a chef as she is a vocalist, which is really unfair.

twi-ny: What are your favorite dishes to make?

mk: Bún bò huế (spicy beef and pork noodle soup), cá kho (caramelized and braised fish), and mì quảng (Quảng noodles).

twi-ny: One final question: Will we ever hear the song you wrote for Alex and Hanah again? And does it have a name?

mk: “I Hear the River Calling.” I don’t perform that song. It was a gift to them. But it might go on an album in the future.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]