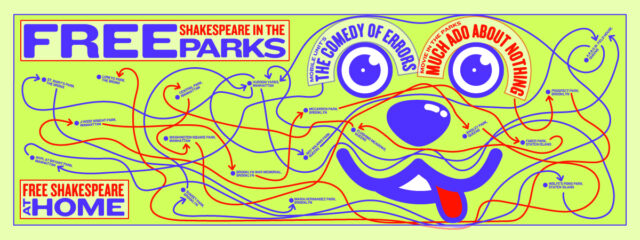

PUBLIC THEATER MOBILE UNIT: THE COMEDY OF ERRORS

Multiple locations in all five boroughs

May 28 – June 30, free (no RSVP necessary)

publictheater.org

Last year the Public Theater’s Mobile Unit presented Rebecca Martínez and Julián Mesri’s terrific bilingual adaptation of William Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors. The production is back for the 2024 summer season, on the road May 28 through June 30, making stops in all five boroughs: the New York Public Library/Bryant Park, Wolfe’s Pond, J. Hood Wright Park, Hudson Yards, Roy Wilkins Park, A.R.R.O.W. Field House, the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, Sunset Park, Travers Park, Maria Hernandez Park, Astor Place, St. Mary’s Park, and the Peninsula at Prospect Park.

No advance reservations are necessary, but you should get there early if you want to get up close and personal with the show; last year I caught it in the Richard Rodgers Amphitheater in Marcus Garvey Park, where some audience members sat on the stage, surrounding the action. If you’re not familiar with the Mobile Unit, you need to be; the program is now in its thirteenth year of bringing free Shakespeare to all five boroughs, presenting works in prisons, shelters, and underserved community centers as well as city parks.

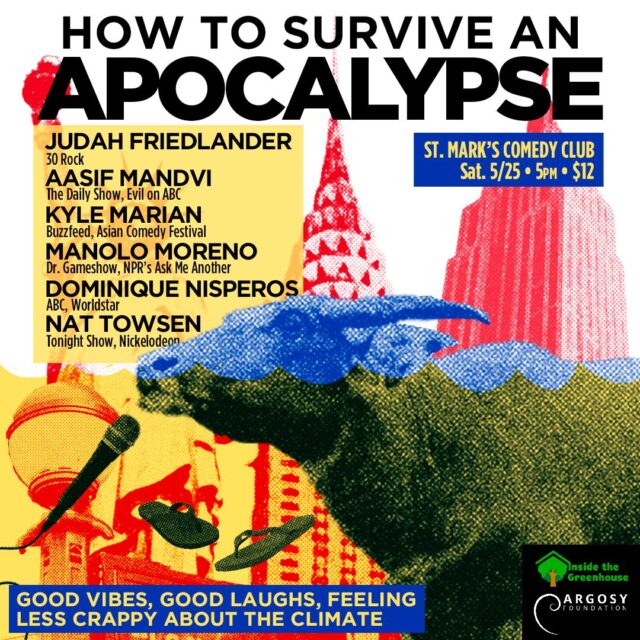

With the Delacorte undergoing renovation, the Mobile Unit is part of “Go Public!,” a festival of free Shakespeare events that includes The Comedy of Errors, outdoor screenings of Kenny Leon’s 2019 Shakespeare in the Park production of Much Ado about Nothing starring Danielle Brooks, Chuck Cooper, Margaret Odette, and Billy Eugene Jones, online streaming of that show as well as 2021’s Merry Wives, 2022’s Richard III, and 2023’s Hamlet, and a block party on July 28.

Below is my review of The Comedy of Errors from last year; I cannot recommend it highly enough.

A fab cast sings and dances its way through exuberant production of The Comedy of Errors (photo by Peter Cooper)

PUBLIC THEATER MOBILE UNIT: THE COMEDY OF ERRORS

Multiple locations in all five boroughs

Through May 21, free (no RSVP necessary)

Shiva Theater, May 25 – June 11, free with RSVP

publictheater.org

The Public Theater’s Mobile Unit touring production of The Comedy of Errors is the most fun I’ve ever had at a Shakespeare play.

The Mobile Unit is now in its twelfth year of bringing free Shakespeare to all five boroughs, presenting works in prisons, shelters, and underserved community centers as well as city parks. On May 13, it pulled into the Richard Rodgers Amphitheater in Marcus Garvey Park, where part of the audience sat on the stage, on all four sides of a small, intimate square area where the action takes place; attendees could also sit in the regular seats, long concrete benches under the open sky.

Emmie Finckel’s spare set features a wooden platform and a bright yellow stepladder that serves several purposes. Lux Haac’s attractive, colorful costumes hang on racks at the back, where the actors perform quick changes. Music director and musician Jacinta Clusellas and guitarist Sara Ornelas sit on folding chairs, performing Julián Mesri’s Latin American–inspired score; Ornelas is fabulous as a troubadour and musical narrator, often wandering around the space and leading the cast in song. The lyrics, by Mesri and director and choreographer Rebecca Martínez, who collaborated on the adaptation, are in English and Spanish and are not necessarily translated word for word, but you will understand what is going on regardless of your primary tongue. As the troubadour explains, “I should mention that most of / this show will be performed in English / though it’s supposed to / take place in two states in Ancient Greece. / But don’t be surprised / if these actors switch their language.”

Trimmed down to a smooth-flowing ninety minutes, the show tells the story of a pair of twins, Dromio (Gían Pérez) and Antipholus (Joel Perez), who were separated at birth. In Ephesus, Dromio serves Antipholus, a wealthy man married to the devoted Adriana (Danaya Esperanza) but cheating on her with a lusty, demanding courtesan (Desireé Rodriguez). The other Dromio and Antipholus arrive in Ephesus and soon have everyone running around in circles as the mistaken identity slapstick ramps up.

Adriana (Danaya Esperanza) and Dromio (Gían Pérez) are all mixed up in The Comedy of Errors (photo by Peter Cooper)

Meanwhile, the merchant Egeon (Varín Ayala) is facing execution because he is from Syracuse, whose citizens are barred from Ephesus, per a decree from the Duchess Solina (Rodriguez); the goldsmith Angelo (Ayala, to be played in 2024 by Glendaliris Torres-Greaux) has made a fancy gold rope necklace for Antipholus but gives it to the wrong one; the Syracuse Dromio is confounded when Adriana’s kitchen maid claims to be his wife; the Syracuse Antipholus falls madly in love with Luciana (Keren Lugo), Adriana’s sister; and an abbess (Rodriguez) is determined to protect anyone who seeks sanctuary.

In case any or all of that is confusing, the troubadour clears things up in a series of songs that explain some, but not all, of the details, and the Public also provides everyone with a cheat sheet. Again, the troubadour: “In case you missed it / or took a little nap / Here’s what’s been happening / since we last had a chat / We’ll do our best / but we confess / this plot is really putting our skills to the test.”

It all comes together sensationally at the conclusion, as true identities are revealed, conflicts are resolved, and love wins out.

Martínez (Sancocho, Living and Breathing) fills the amphitheater with an infectious and supremely delightful exuberance. The terrific cast interacts with the audience, as if we are the townspeople of Ephesus. Gían Pérez (Sing Street) and Joel Perez (Sweet Charity, Fun Home) are hilarious as the two sets of twins, who switch hat colors to identify which brother they are at any given time. Esperanza (Mary Jane, for colored girls . . .) shines as the ever-confused, ultradramatic Adriana, Lugo (Privacy, At the Wedding) is lovely as Luciana and the duchess, Rodriguez is engaging as Emilia and the courtesan, and Ayala (The Merchant of Venice, The Taming of the Shrew) excels as Angelo, Egeon, and Dr. Pinch.

But Ornelas (A Ribbon About a Bomb, American Mariachi) all but steals the show, switching between leather and denim jackets as she portrays minor characters and plays her guitar with a huge smile on her face, words and music lifting into the air. Charles Coes’s sound design melds with the wind blowing through the trees and other people enjoying themselves in the park on a Saturday afternoon. There are no errors in this comedy.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]