VS.

Mabou Mines

August 6-8, suggested donation $10

www.maboumines.org

Founded in 1970 by JoAnne Akalaitis, Lee Breuer, Philip Glass, Ruth Maleczech, and David Warrilow, Mabou Mines has presented multidisciplinary experimental works at such New York City venues as the Guggenheim, the Whitney, the Kitchen, Paula Cooper Gallery, Theater for the New City, the Performing Garage, La MaMa, the Public Theater, the Skirball Center, Classic Stage, HERE Arts Center, St. Ann’s, New York Theatre Workshop, and Abrons Arts Center during its legendary, influential half-century history. Amid a pandemic lockdown, it has now turned its attention to Zoom for its latest production, Carl Hancock Rux’s virtual Vs., continuing August 6-8. The fifty-minute piece was written by Rux and directed by Mallory Catlett, the two new co-artistic directors of the East Village–based company.

Vs. channels Franz Kafka, Hélène Cixous, Audre Lorde, and James Baldwin through an absurdist lens as four figures are brought before an interrogator, answering the same repetitive bureaucratic questions with a sly didacticism and a tongue-in-cheek pedantry amid the language of rhetoric —or the rhetoric of language. The four witnesses are played by Becca Blackwell, David Thomson, Mildred Ruiz-Sapp, and Perry Jung; the audience serves as the visual component of the monotone interrogator, who is heard off camera. Beware of your Zoom background, because you will occasionally be front and center, your face and body covered by a black silhouette (unless you move), as if you are the anonymous interviewer.

Innocuous questions are answered with mini-essays that will make you feel like you’re back in grad school, except now with a sense of humor. When asked if they were born in November, the first witness testifies, “Not if we are to consider an opposition to phallogocentricism and the hegemonic ideals contained in patriarchal culture uniting theory and fantasy, challenging such discourse within the frameworks of a constitution blown up by law. Certainly not if we are to consider language as a central trope and your appropriation and adaptation of language, or challenge to, genre (as language); or the anarchic strategy of regulating forces of hegemonic and phallogocentric culture encoded in language and hierarchical oppositions or distinctions between what I am and what you are; between what is black or white, man or woman. Not if we are to ignore the elementary rubrics of binary principles which lie at the heart of most human structures.”

If you didn’t already know you were in for something different, you’ll start realizing it when the second witness gives the same exact answers as the previous one, word for word.

The third witness responds only in Spanish, giving the most emotional answers (which are translated in the chat). Asked about being born in November, they declare, “Why do you keep asking me if I was born in November? Who cares? I said I don’t know. Ay, what are you, crazy? . . . Stop asking me where I am from and when I was born; did I ask you personal questions?”

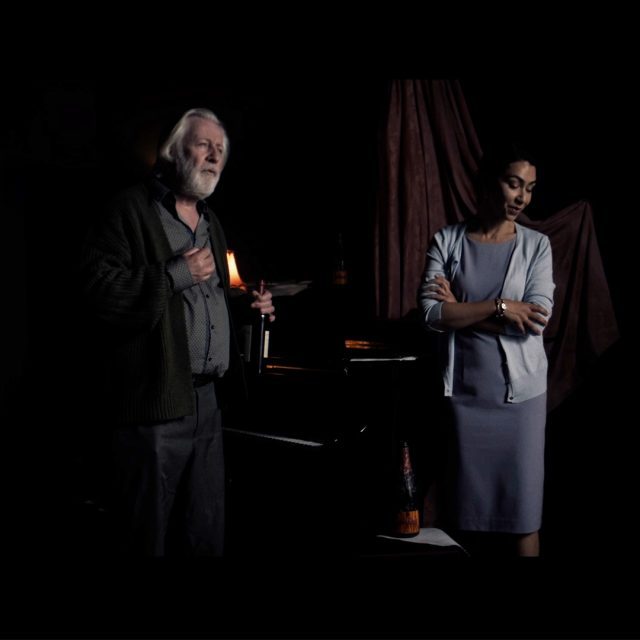

Four witnesses make their case in Mabou Mines’ virtual Vs.

Finally, the last witness, asked if they want a glass of water, responds, “God forbid, if there be a God, I prefer something other than water. Something untainted by conservatives, that would be cool. Let’s both have one. You can tell so much about a person by what zie, zim, zir, zieself, sie, sie, hir, hirs, hirself, ey, em, eir, eirs, eirself, ve, ver, vis, vers, verself, tey, ter, tem, ters, tersel, e, em, eir, eirs, emself are drinking. Whether the drinker is loved, or has loved at all. Whether the drinker is now or long ago. Whether the drinker is drinking first harvest, or near the end. Bird of prey? Predator?”

During each interrogation, digital designer Onome Ekeh fiddles with the technology, playing around with color and resolution, making the witnesses go out of focus or disappear into backgrounds, surrounding them with random objects, or creating multiple versions of them. Just as the four subjects refuse to take the questions seriously, they also won’t let their identities be clearly delineated. We learn nothing about who they are, why they are there, or what the interrogator is trying to find out, although the truth seems to be at the center of it all, whatever that is. (Am I referring to the truth or the center there? I honestly don’t know.) “The danger is you, and this council, and this hearing, and this senate, and its polity, paying too much attention to a conciliatory approach to existence,” one witness says. “The first shall go. The last shall come. Age comes. The body withers. Truth comes as itself, a dissembling.”

Throughout the show, you can watch the reactions of your fellow audience members. While I found much of the play very funny in a sarcastic, screw-authority kind of way, it appeared that I was the only one laughing. It’s certainly not a comedy, nor is it a purely academic look at an insecure future. Well, actually, it might be that. In a statement about the production, Rux, a poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, actor, director, singer, and songwriter, explains, “The last four years of American — and for that matter, global — politics has revealed repetitive yet unprecedented abject horror as it relates to historical oppression and colonialism. Vs. attempts to engage the audience in a tribunal of sociopolitical rifts; a discourse that may or may not attempt to lay blame on a nation state and that ultimately reveals the nation state to be ‘us,’ or, rather, ‘we the people.’ The questions it attempts to address are complicated and yet quite simple: What is the history of oppression? Who are the oppressed? What is the final and definitive language of freedom, justice, and liberty for all? What are our tools for human survival?”

Rux (Talk, The Baptism) is not joking around there, making important points about where we are as a culture in the twenty-first century. The same points are dealt with in the play, just not so directly. If you take it completely seriously, you might be bored with the repetition and the apparent lack of advancement of the narrative. But seek out the satirical bent to better appreciate its unique style. Otherwise, God help us all, if there is a God.