Five siblings face a tragedy they cannot recover from in The Macaluso Sisters

THE MACALUSO SISTERS (Emma Dante, 2020)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Opens Friday, August 6

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

Emma Dante’s The Macaluso Sisters is a heart-wrenching tale that follows seventy years in the lives of five sisters in Palermo, Sicily, after they endure a horrific tragedy. The film begins in 1985, as the orphaned siblings prepare for a day at the beach, which they have to sneak onto because they can’t afford the admission fee. It is a chance for them to enjoy themselves and be free of their problems for an afternoon, much like the pastel-painted pigeons they raise and rent out for special occasions, from weddings to funerals. The oldest, eighteen-year-old Maria (played first by Eleonora De Luca, then Simona Malato), uses the escape to secretly share kisses with a young woman she is in love with as they set up an outdoor screening of Back to the Future.

Pinuccia (Anita Pomario, Donatella Finocchiaro, Ileana Rigano) spends much of her time in front of mirrors, putting on makeup and getting ready to attract men. Lia (Susanna Piraino, Serena Barone, Maria Rosaria Alati) is the most passionate and impulsive member of the family. Katia (Alissa Maria Orlando, Laura Giordani, Rosalba Bologna) is the chubby, imaginative one who embraces fantasy. And Antonella (Viola Pusateri) is the beloved baby of the close-knit group, cute and adorable, whom the rest dote over. Following a terrible accident, the four remaining sisters try to go on with their lives, but they are haunted by loss, literally and figuratively, some damaged beyond repair as the decades pass.

Written by Dante, Elena Stancanelli, and Giorgio Vasta based on Dante’s play Le sorelle Macaluso, the award-winning film is centered around the sisters’ home, which grows more ramshackle over time, representing their deteriorating psychological state. Dante (Via Castellana Bandiera, mPalermu) often trains the camera on the building’s yellowing facade, four floors with many windows, tiny terraces, and a rooftop extension where the pigeons live. Just like the birds always return, so do the surviving sisters, the sadness enveloping them, pain evident in their vacant eyes and aging bodies.

Dante has described the five siblings as parts of the same being, with Maria the brain, Pinuccia the skin, Lia the heart, Katia the stomach, and Antonella the lungs, each one necessary to maintain the whole; take away any single aspect and the body is in danger of failing. It is no coincidence that the middle-aged Maria works in a veterinary lab where she has to cut open animals and dispose of their internal organs, saving the heart in a plastic bag. Meanwhile, whenever the older Katia, the only one who develops some sort of life of her own and is in favor of selling the place, tries to go inside, her key won’t open the door, as if she is no longer welcome, the house aware of her intentions.

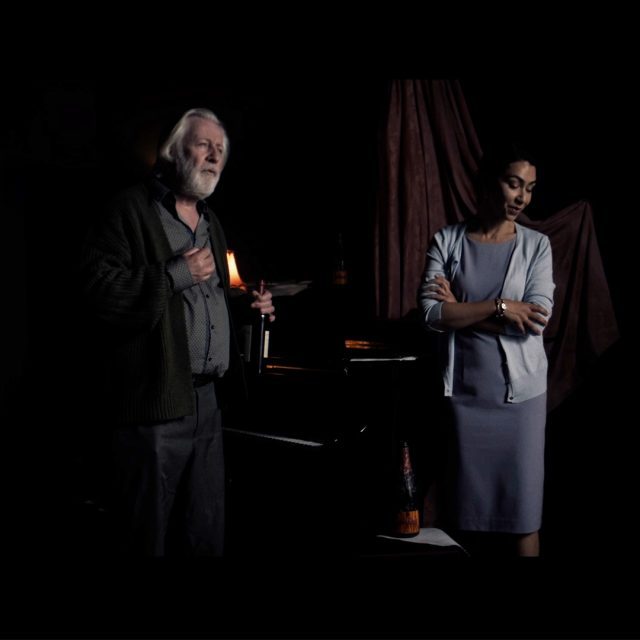

Antonella (Viola Pusateri) is the beloved youngest of the Macaluso sisters in elegiac film

The elegiac film is gorgeously photographed by Gherardo Gossi, capturing the beauty of the bright outdoors, filled with life and excitement, offset against the darkness of the family home, shadows everywhere. Occasionally one of the sisters looks through a hole in the wall they made as children, allowing them to see a sunny world that has eluded them. Throughout the film, Dante focuses on water, from the ocean to the bathtub where the young Antonella likes to play and the older Maria seeks respite.

Dante lingers on Maria more than the others; as a teenager, she dreams of becoming a dancer, her lithe, naked body alive with promise. But decades later, her once-wide eyes are tired, deep, dark circles dominating her face; as she soaks in a tub, we again see her naked body, but it lacks the vitality she previously reveled in, doomed to a different fate, not simply because of age but because she, like her sisters, have never been able to get over their loss. It’s like the fancy plate Antonella uses to feed the pigeons; when it breaks years later, Maria tries to glue it back together, but she cannot fill in all the cracks.