Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Comtesse d’Haussonville, oil on canvas, 1845 (Purchased by the Frick Collection, 1927)

FRICK MADISON AND THE SLEEVE SHOULD BE ILLEGAL

945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street

Thursday – Sunday, $12-$22 (includes free guide), 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

www.frick.org/madison

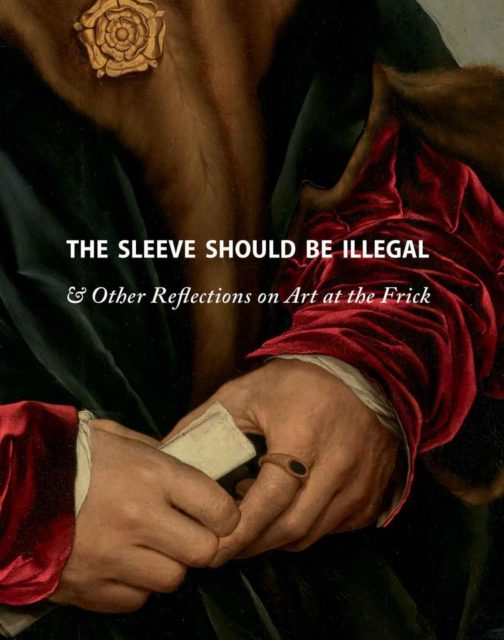

For the first twelve months of the pandemic, the Frick, my favorite place in New York City, was my “virtual home-away-from-home” when it came to art. And I mean that in a different way than Lloyd Schwartz does in his piece on Johannes Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl in the recently published book The Sleeve Should Be Illegal & Other Reflections on Art at the Frick, in which the poet and classical music critic uses that phrase to describe what the museum, opened to the public in 1935 at Fifth Ave. and Seventieth St., meant to him when he was growing up in Brooklyn and Queens. The book features more than sixty artists, curators, writers, musicians, and philanthropists waxing poetic about their most-admired work in the Frick Collection.

A native of Brooklyn myself, I am referring specifically to the institution’s online presence during the coronavirus crisis. It had closed in March 2020 for a major two-year renovation, moving its remarkable holdings to the nearby Breuer Building on Seventy-Fifth and Madison, the former home of the Whitney from 1966 to 2014, then host to the Met Breuer for an abbreviated four years. Starting in April 2020 and continuing through last month, chief curator Xavier F. Salomon (and occasionally curator Aimee Ng) gave spectacular prerecorded illustrated art history lectures on Fridays at 5:00 focusing on one specific work in the museum’s holdings; thousands of people from around the world tuned in live to learn more about these masterpieces. Two questions added a frisson of excitement for devoted fans: What cocktail would the curator select to enjoy with the painting, sculpture, or porcelain/enamel object that week? And which smoking jacket would Xavier be rocking? These sixty-six marvelous “Cocktails with a Curator” episodes can still be seen here.

For more than half my life, the Frick has been the spot I go to when I need a break from troubled times, a respite from the craziness of the city, a few moments of peace amid the maelstrom. Going to the Frick, which was designed by Carrère and Hastings and served as the home of Pennsylvania-born industrialist Henry Clay Frick from 1914 until his death in 1919 at the age of sixty-nine, was like visiting old friends, reflecting on my existence among familiar and welcoming surroundings. There is still nothing like sitting on a marble bench in John Russell Pope’s Garden Court, with its lush plantings, austere columns, and lovely fountain, in between continuing my intimate, personal relationships with cherished canvases. In Sleeve, philanthropist Joan K. Davidson writes about Giambattista Tiepolo’s Perseus and Andromeda, “Entering the Frick, the visitor tends to head to the galleries where the Fragonards, Titians, El Greco, the great Holbeins, and other Frick Top Treasures are to be found. Or, perhaps, you turn left to the splendid English portraits in the Dining Room. But not so fast, please. You could miss my picture!” I am not nearly so generous as Davidson, not at all ready to share my prized works with others, preferring alone time with each.

After being teased by Salomon’s discussion of Rembrandt’s impossibly powerful 1658 self-portrait, which gave a glimpse of where it is on display at Frick Madison, it was with excitement and more than a little trepidation that I finally ventured toward Marcel Breuer’s Brutalist building, worried it would feel like seeing friends in a hotel where they’re staying while their kitchen is being remodeled. As artist Darren Waterston admits in his piece on Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert, about his first pilgrimage to the museum, “I remember feeling a nervous anticipation as I approached the Frick, as if I were meeting a lost relative or a new lover for the first time.” He now makes sure to return at least once every year.

In addition, I was poring over Sleeve, a cornucopia of Frick love. Many of the rapturous entries are just as much about the institution itself and how the pieces are arranged as the chosen object. Writing about the circle of Konrad Witz’s Pietà, short story writer and translator Lydia Davis explains, “Because of the reliable permanence of the collection — the paintings usually hanging where I knew to find them — they became engraved in my memory. Over time, of course, I changed, so my experience of the paintings also changed.” Fashion designer Carolina Herrera, praising Goya’s Don Pedro, Duque de Osuna, notes, “I would love to move in. And, as one does, I would like to move the furniture around, hang the paintings in different places, and put some of the objects away, to change them from time to time.”

While I had contemplated moving in, I had never considered rearranging anything, although I was blown away when, after decades of seeing Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait of Sir Thomas More in the Living Hall, where it looks over at Holbein’s portrait of More’s archnemesis, Sir Thomas Cromwell, well above eye level and separated by a fireplace and El Greco’s exquisite painting of St. Jerome, I was able to belly up to the canvas at my height when it was displayed temporarily in the Oval Room, leaving me, as curator Edgar Munhall pointed out on the audio guide, “weak in the knees.” Entering Frick Madison, my thoughts zeroed in on my impending rendezvous with Holbein and More.

Unknown artist (Mantua?), Nude Female Figure (Shouting Woman), bronze with silver inlays, early 16th century (Henry Clay Frick Bequest)

Five people melt over the More portrait in Sleeve; in fact, the title of the book comes from novelist Jonathan Lethem’s foray into the work. Nina Katchadourian raves, “Every time I visit the Frick, I go to the Living Hall to look at Holbein’s portrait of Sir Thomas More. I love it as a painting, but I also see it as the first spark in a series of chain reactions that happen among objects in the room. . . . It is a staging of masterpieces that is itself a masterpiece of staging.” I quickly found the canvas, in its own nook with Cromwell, as if there were nothing else in the world but the two of them. You can get dangerously close to the breathtaking canvases, glorying in Holbein’s remarkable brushwork, his unique ability to capture the essence of each man in a drape of cloth, a ring, a stray hair, a bit of white fabric sticking out from a fur collar.

Utterly pleased and satisfied with the placement of the Holbeins — while I did miss all the finery usually surrounding them, seeing them both so unencumbered just felt right — I continued my adventure to track down other old friends and make new ones. St. Francis in the Desert, a work that demands multiple viewings, with new details emerging every time, usually hangs across from More, but here it has its own well-deserved room. Referring to St. Francis’s position in the painting, hands spread to his sides, looking up at the heavens, artist Rachel Feinstein writes, “That moment of isolation is fascinating in the context of the situation we are in now because of COVID-19. Our family of five may not be living alone in a cave right now, but due to the current circumstances, we have turned more inward, like St. Francis. Looking at this image and its sharp clarity during this time of fear and uncertainty is very soothing and inspirational.”

Trips to the Frick bring up childhood memories for many Sleeve contributors (Lethem, Moeko Fujii, Bryan Ferry, Stephen Ellcock, Julie Mehretu); describing seeing Rembrandt’s Polish Rider for the first time in high school, novelist Jerome Charyn remembers, “He could have been a hoodlum from the South Bronx with his orange pants and orange crown. . . . I left the Frick in a dream. I had found a mirror of my own wildness on Fifth Avenue, a piece of the Bronx steppe.” Donald Fagen and Abbi Jacobson recall lost love, while Frank, Edmund De Waal, and Adam Gopnik bring up Marcel Proust. Arlene Shechet and Wangechi Mutu find the feminist power in the early sixteenth century sculpture Nude Female Figure (Shouting Woman). “Making a small work is an unforgiving process,” Shechet writes. “There is no room for missteps, and the Shouting Woman is an example of exquisite perfection, her bold demeanor wrought with great feeling and delicacy. The plush palace that is the Frick becomes eminently more compelling when I visit with this giant of a sculpture.”

Artist Tom Bianchi gets political when delving into Goya’s The Forge, a harrowing canvas that depicts blacksmiths hard at work as if in hell. “The presence of The Forge in the collection is an anomaly,” Bianchi explains. “Frick’s fortune was built on the labor of steelworkers, whose union he infamously opposed. His reduction of the salaries of his workers resulted in the Homestead strike in 1892, in which seven striking workers and three guards were killed and scores more injured. Ultimately, Frick replaced the striking workers, mostly southern and eastern European immigrants, with African American workers, whom he paid a 20 percent lower wage. One wonders if Frick appreciated the irony of the inclusion of this painting among his Old Masters.”

Agnolo Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano), Lodovico Capponi, oil on panel, 1550–55 (The Frick Collection; Henry Clay Frick Bequest)

I’ve always had a minor issue with how the Frick’s three Vermeers, Officer and Laughing Girl, Mistress and Maid, and Girl Interrupted at Her Music, are displayed; two of the three can usually be seen in the South Hall, above furniture, in a narrow space that is easy to pass by, especially if you are checking out the opposite Grand Staircase, which will at last be open to the public when the Frick reopens in mid-2023.

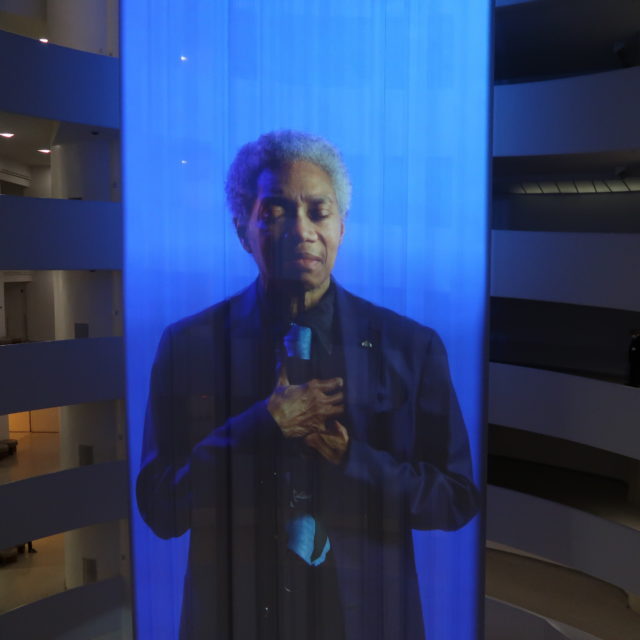

There are no such obstacles at Frick Madison, where all three are in the same room on the second floor. Together the Vermeers are feted by Fujii, Frank, Vivian Gornick, Gregory Crewdson, Susan Minot, Judith Thurman, and Schwartz. Meanwhile, various artists are completely shut out of Sleeve accolades, including Hans Memling (Portrait of a Man), Frans Hals (Portrait of an Elderly Man and Portrait of a Woman), François Boucher (The Four Seasons), Edgar Degas (The Rehearsal), John Constable (Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds), Carel Fabritius (The Goldfinch), François-Hubert Drouais (The Comte and Chevalier de Choiseul as Savoyards), Paolo Veronese (Wisdom and Strength), and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (La Promenade). Rembrandt’s aforementioned self-portrait receives five nods (Roz Chast, Rineke Dijkstra, Diana Rigg, Jenny Saville, Mehretu), while Ingres’s Comtesse d’Hassuonville nets three (Jed Perl, Firelei Báez, Robert Wilson).

But the biggest surprise for me was the popularity of Bronzino’s Lodovico Capponi, chosen by Susanna Kaysen, David Masello, Daniel Mendelsohn, Annabelle Selldorf, and Catherine Opie. When I saw it at Frick Madison, I had no recollection whatsoever of the 1550s vertical oil painting of a page with the Medici court; it felt like I was seeing it for the very first time. It’s an arresting picture, highlighted by loose background drapery, the curious position of the fingers of each hand, the privileged look in his eyes, and, of course, the ridiculously funny codpiece/sword. As I stood in front of it, it did not strike me the way other portraits at the Frick do; in her “Cocktails with a Curator” entry on the piece, Ng says with a big smile, “This one really is one of my most favorite, if not favorite, works at the Frick. . . . I know I’m not the only one. . . . This is a painting that’s at the heart of many people who are close to the Frick.” When I go back to Frick Madison, which will be very soon, I’m going to spend more time with Lodovico, and I am already preparing myself to make a beeline for it when the original Frick reopens. I clearly must be missing something, as Lodovico has taken a brief sojourn to the Met, where it is not only included in the major exhibition “The Medici: Portraits and Politics, 1512–1570,” which runs through October 11, but is the cover image of the catalog.

Selldorf writes in her piece on Lodovico, “Art informs the space, but the space also informs the art.” Whether it’s the Frick Madison or the Frick on Fifth, “The genius, beauty, and mystery behind its doors may change your life,” Herrera promises. It’s changed myriad lives over its nine-decade existence, from other artists’ to just plain folks’ like you and me. You’re bound to fall in “love at first sight” — as New York Philharmonic principal cellist Carter Brey describes his initial encounter with George Romney’s Lady Hamilton as “Nature” — with at least one work at the Frick, something that will stay with you for a long time, an objet d’art you’ll visit again and again and develop a meaningful relationship with over the years. Just be sure to stay out of my way when I’m reconnecting with Sir Thomas More.