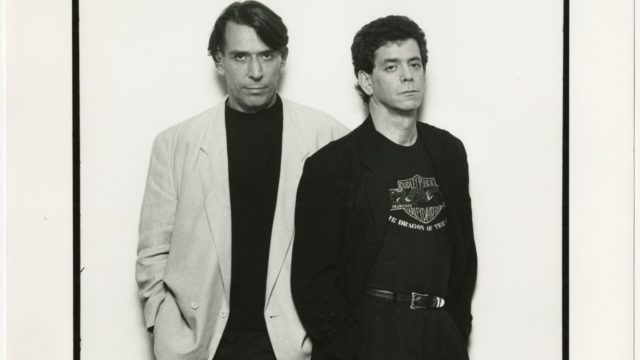

Worlds Fair Inn explores nuclear annihilation and serial killing with a vaudeville sensibility (photo by Regina Betancourt)

ENCORE PRESENTATION: WORLDS FAIR INN

Axis Theatre

One Sheridan Sq. between West Fourth & Washington Sts.

Thursday – Saturday through October 23, $10-$30, 8:00

866-811-4111

www.axiscompany.org

On March 11, 2020, I was in Axis Theatre Company’s small, intimate downstairs space at One Sheridan Square, getting ready to watch artistic director Randy Sharp’s adaptation of Henry James’s Washington Square. Shortly before the show started, a few of us chuckled as a woman roamed the aisles, unable to choose a seat. (The venue is general admission.) When she was right behind me, I heard her mutter, “I’m not going to get sick. This virus is not going to get me.” A few of us looked at one another, thinking she had gone a bit overboard. Little did I know that Washington Square would be the last live theater with actors and an in-person audience I would experience for nearly fifteen months because of a virus that has killed more than six hundred thousand Americans and shuttered live entertainment venues around the globe.

On June 4, 2021, there I was, back at the Axis Theatre, to see my first indoor play with actors and an audience since the pandemic lockdown was lifted. It was the premiere of Sharp’s Worlds Fair Inn, performed by a cast of five to an audience of fifteen people in masks. Not only was it thrilling to be in the theater, but the hourlong work is a fab absurdist journey through madness and tragedy, a strange and enticing mix of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein, and the Three Stooges.

Axis producing director Brian Barnhart stars as Frank, a creepy character right out of a low-budget Roger Corman horror-comedy, a composite of Victor Frankenstein, the fictional mad scientist who built a creature out of dead bodies; theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, “the father of the atomic bomb”; and H. H. Holmes, a con artist and serial killer who owned the World’s Fair Hotel, aka the Murder Castle, near the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Two loony bowler-hatted fellows, Eric (George Demas) and Bill (Jon McCormick), arrive at the inn, seeking shelter and company. All three men wear dark clothing and giant Frankenstein-style shoes on a set littered with dozens of bottles of whiskey, a hotel front desk that doubles as a killing casket, and a neon sign advertising the name of the place. The set is designed by Sharp, with period costumes by Karl Ruckdeschel, fun props by Lynn Mancinelli, eerie lighting by David Zeffren, and playfully sinister sound and music by former Blondie member Paul Carbonara.

“What do you think it would take to make a living man out of a bunch of cut-up dead people? I mean if you cut them up and glued them together?” Frank, who boasts that he’s a scientist, a doctor, an American, and an architect, asks.

“Why wouldn’t you use whole dead people and bring them back to life?” Eric answers, pauses, then adds, “Oh! Maybe you need separate parts so you can see how to make them work? Then stick them back?”

“Right,” Frank responds. “Or maybe I would just use the whole person. I’m an architect. It’s scientific. I just want to see what happens.”

Eric and Bill jump at the chance to help Frank in his unnatural mission, displaying no hesitancy at the prospect of killing people, chopping them up, then assembling the pieces into a new whole. “We’re builders,” Bill offers. “Not scientists. Just to be sure. We can fix things! Hard workers! . . . We’re contractors!”

Frank’s first two victims are Machine (Edgar Oliver), an erudite oddball, and Lady (Britt Genelin), a coquettish factory worker; both fall for the men’s ruse, undone by their own pride in their willingness to embrace new ways.

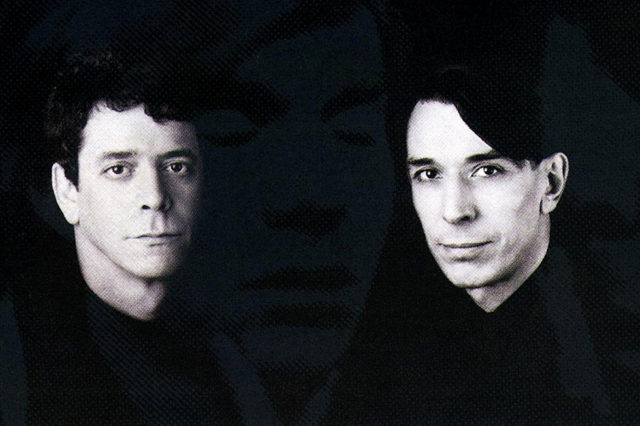

Lady (Britt Genelin) brings light to the dark proceedings of Worlds Fair Inn (photo by Regina Betancourt)

Worlds Fair Inn feels like a uniquely charming, deranged vaudeville act with Moe/Shemp (Frank), Larry (Bill), and Curly (Eric) filtered through Corman’s Tales of Terror. The cast is wonderfully over the top, highlighted by the risible interplay between Demas (Maverick, Last Man Club) and McCormick (Dead End, Donkey Punch). Pay particular attention to McCormick even when he’s not talking; he moves in herky-jerky fits and starts, overcome by nerves and fear, often leaving his thoughts unfinished as his eyes dart about the stage.

Barnhart (High Noon, Dead End) channels Angus Scrimm from Phantasm and John Carradine in Woody Allen’s Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask) as he delivers his lines with great bombast. It’s fab to see Oliver, a solo specialist who has presented In the Park, East 10th St.: Self Portrait with Empty House, and Attorney Street at Axis, as part of an ensemble; he and Genelin (Washington Square, High Noon) are adorable as vaudeville versions of the Creature and the Bride of Frankenstein, trapped in a skit they don’t fully comprehend.

Writer-director Sharp (Strangers in the World, Seven in One Blow) adeptly maneuvers between high and low comedy as she takes on nuclear annihilation, a different kind of rather effective serial killing — Frank, Eric, and Bill bow every time Japan is mentioned — and melds Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory, Oppenheimer’s Los Alamos, and Holmes’s murder hotel into a supremely funny and memorable show. As we finally emerge from this dark year, we may not have much hope for the future of humanity, but Axis gives us hope for the future of theater. (And I hope the woman I foolishly chuckled at in March 2020, before Washington Square at the Axis, is alive and well and gets to catch this terrific satire, as you should too. And now you have an added opportunity, as the play is back for a well-deserved encore run September 30 through October 23.)