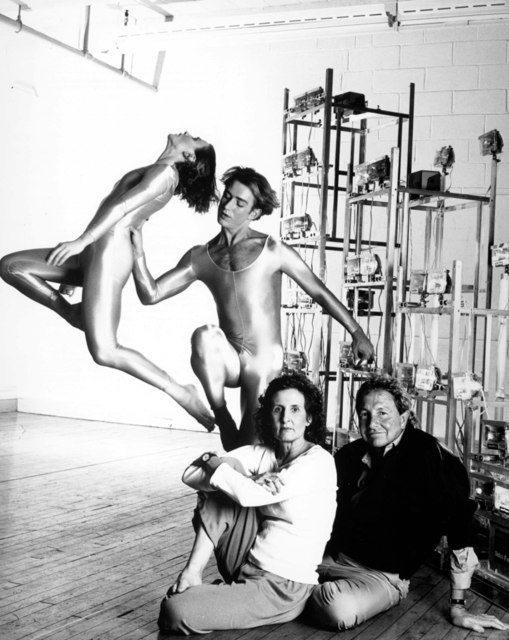

Five women believe they are on their way to a better life in Belfast Girls (photo by Carol Rosegg)

BELFAST GIRLS

Irish Repertory Theatre, Francis J. Greenburger Mainstage

132 West 22nd St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Wednesday – Sunday through June 26, $50-$70

212-727-2737

irishrep.org

“From now on on this ship we’re to be mistresses of our own destiny,” Judith Noone declares early in Belfast Girls, which opened tonight at the Irish Rep. Moments later, she adds, “Youse think the English poor are any better off than us? They’re not. An’ besides, we’re women. An’ we’ll never be anythin’ here. For we are as the peat; to be used up an’ walked on.”

During the Great Famine, also known as the Great Starvation, the Orphan Emigration Scheme was put into effect in Ireland by British secretary of state for the colonies Earl Grey, purportedly to send young, parentless Irish girls (nineteen and under) who had been toiling in overcrowded workhouses to a better life in Australia. Between 1848 and 1850, more than four thousand women made the treacherous months-long journey by ship; however, many of them were not orphans but older prostitutes who had been soliciting on the streets. Their occupation would be quite a surprise to the Australian men who were supposed to be waiting for them with open arms on the shores of the faraway continent.

London-born Irish playwright Jaki McCarrick tells the fictionalized story of one such harrowing trip in Belfast Girls, making its New York City debut at the Irish Rep through June 26. It’s 1850, and the Inchinnan, the name of a real ship, is about to set sail. Four Catholic girls from Belfast have been assigned a small room with two bunks, Judith (Caroline Strange), Hannah Gibney (Mary Mallen), Ellen Clarke (Labhaoise Magee), and Sarah Jane Wylie (Sarah Street). At first, it’s like a dorm room at a girls school, one none of them would have been able to afford. They poke fun at one another while also hoping for a different future than the one they had been destined for.

When Hannah and Ellen take an immediate liking to the (unseen) attractive male cook, Judith, the most no-nonsense of the group, tells them to stay away from the men onboard. “All a youse, get your heads round the plain fact we’re leavin’ an’ we won’t ever be comin’ back,” she says. “Look, I know some of youse an’ youse know me. We have this one an’ only chance. An’ in all the kingdom of Ireland aren’t we — us women — aren’t we damned lucky to be gettin’ out of it?”

Molly (Aida Leventaki), Judith (Caroline Strange), and Hannah (Mary Mallen) take a break on board the Inchinnan (photo by Carol Rosegg)

A few moments later, Hannah says, “I hear there’s fine English farmers in the colony with thousands of acres, Judith, an’ more cattle than ya could dream of seein’ in the whole of Ireland, just drippin’ wit need for female companionship.” Ellen responds, “I want no damn Englishman. Haven’t they been trouble enough in this country? Why in the name a god would I travel halfways across the earth ta find one of them when every self-respectin’ Irishman is tryin’ to get them outta the place?”

Hannah, Sarah, and Judith are none-too-pleased when Ellen, who had gone for a walk, comes back with Molly Durcan (Aida Leventaki), a whisper-thin maidservant from the much wealthier county of Sligo who will be staying with them as well. Hannah is suspicious of Molly, but the five women attempt to bond through a terrible storm and some surprising revelations. And for good measure, McCarrick adds an Irish ghost story and several traditional folksongs.

In Belfast Girls, McCarrick (Leopoldville, The Naturalists) takes on such issues as class, gender, and religion, adding a dose of Marxism, all seen through a feminist lens as the women contemplate what’s next for them. They talk a lot about what was considered women’s responsibilities a hundred and seventy years ago: being a maidservant, sewing adornments on bonnets, not learning how to read, existing primarily as birthing vessels.

“When I arrive in the Colony what choice do I have only to work as I always worked?” Sarah asks. Molly answers, “But you do have choices. There are groups starting all over the world. Where women stand up and talk and demand the privileges only men have now; to be paid as men are paid, to be allowed to do the same things — to tour in a theatrical, for instance, without people thinking you’re loose or worse.” Molly has dreams of being an actress, perhaps playing Puck in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a character who, as Robin Goodfellow in the play within the play, says, “Lord, what fools these mortals be! . . . Follow my voice: we’ll try no manhood here.” But all five of the women are acting, adapting their personas, and toying with the truth, in order to get away from their miserable lives.

Judith (Caroline Strange), Ellen (Labhaoise Magee), and Hannah (Mary Mallen) contemplate their future in Belfast Girls (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Director Nicola Murphy (A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, Pumpgirl) keeps a fast pace and steady ship as controversies ensue and truths come out. Chika Shimizu’s two-story set is like a kind of liminal prison for the women, cramped in a room with no windows. China Lee’s costumes emphasize the type of restrictive clothing women had to wear at that time. Caroline Eng’s sound puts the audience on the water, birds chirping outside, tempting freedom. The only male member of the primary cast and crew is lighting designer Michael O’Connor.

The cast is exemplary, led by Strange (London Assurance, Meditations on a Magnetic North) as the Jamaican-born mixed-race Judith; her last name, Noone, might imply that she is “no one,” but she is a force to be reckoned with, unafraid to defend her decisions in a patriarchal society. “We didn’t leave Ireland at all, ladies,” Judith declares. “Ireland has spat us out.” The Orphan Emigration Scheme ended in 1850, but the battle for women’s rights in Ireland continues.