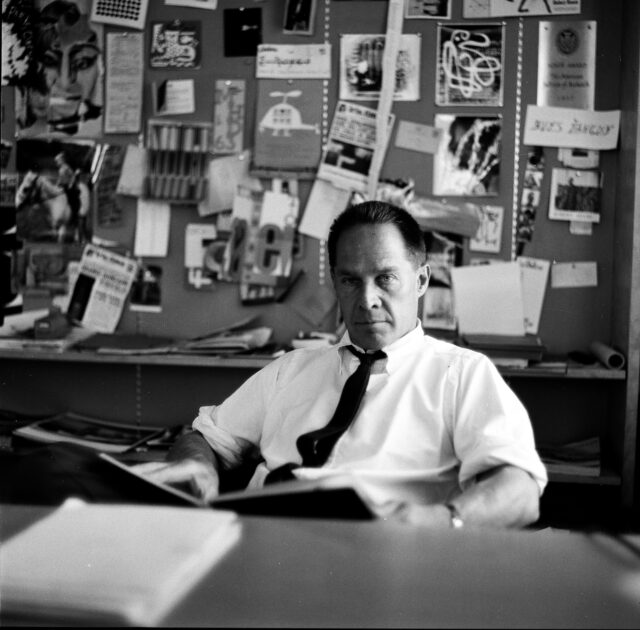

Modernism, Inc. subject Eliot Noyes is hard at work in his New Canaan office (courtesy of the Pedro Guerrero Estate)

MODERNISM, INC. (Jason Cohn, 2023)

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St.

Opens Friday, July 19

212-924-7771

www.ifccenter.com

“Good design is good business” was the mantra employed by architect Eliot Noyes, who, with IBM CEO Tom Watson Jr., helped rebrand the company through its public image from top to bottom, from its logo to the look of its products, creating a legacy that is still in evidence today.

Noyes’s career is detailed in Jason Cohn’s documentary Modernism, Inc., opening July 19 at IFC Center, with Cohn on hand for Q&As on Friday and Saturday night at the 6:50 screening.

The eighty-minute film skips over Noyes’s childhood, beginning with his disgruntlement with the old-fashioned ideas taught at Harvard in the 1930s. In 1937, he started studying with German American architect and Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and never looked back. Noyes wanted to incorporate the reality of modern life, including social and economic problems, into his work. “Gropius pushed Noyes to see the continuity between art, architecture, and the design of everyday objects, what Gropius called the total theory of design,” narrator and French actor Sebastian Roché explains.

In 1939, Noyes, who was born in Boston in 1910, was hired as the first director of industrial design at the Museum of Modern Art, where he staged the important 1941 exhibition “Organic Design in Home Furnishings.” He enlisted in the Army Air Force during WWII, exploring the efficacy of using gliders in battle. He espoused his theory of design on the television program Omnibus. From 1947 to 1960, he wrote an influential column for Consumer Reports called “The Shape of Things.”

In 1956, one of his colleagues on the Pentagon’s glider project, Watson, brought him over to IBM to remake its corporate culture; Noyes refused to become a full-time employee, instead accepting the position of consultant director of design, working from his home in New Canaan, Connecticut, where he and his wife, Molly Weed, who contributed to many of his designs, raised four children: Eli, Fred, Meridee, and Derry. New Canaan became a hub for designers, as Marcel Breuer, Philip Johnson, Joe Johansen, and others soon moved into the exclusive suburb.

Eliot Noyes was IBM’s consultant director of design from 1954 to 1977 (courtesy of the Eliot Noyes Family)

“Eliot Noyes had quite a curious view of Modernism, a deep-seated belief that design could be at the core of building a future society,” design historian Alice Twemlow says in the film. Noyes’s designs, from the conversation chair, IBM Selectric, and large computers to logos for such companies as IBM, Mobil, Westinghouse, Pan Am, and Xerox to his unique houses, felt as new as free jazz and abstract expressionism, interweaving form and function. He collaborated with such industry luminaries as Charles Eames and Paul Rand, known as “Matisse on Madison Ave.” Not everything was successful; one notable failure was his bubble house.

Describing what went into constructing a house for her family in 1978, Lyn Chivvis, interviewed in her Noyes-designed kitchen with her husband, Arthur, tells Cohn, “El was able to talk to his clients, my parents and us, and find out, what do you need for your daily life? El developed the open-shelving idea. He actually measured the shelves for me. It doesn’t fit you. It doesn’t fit you, it doesn’t fit anyone else but me.”

Cohn also speaks with IBM design head Katrina Alcorn, Noyes biographer Gordon Bruce, IBM chief archivist Jamie Martin, University of Toronto architecture professor and historian John Harwood, IBM design manager Tom Hardy, design historian Thomas Hine, and Noyes’s children, integrating archival footage, home movies, industrial films, and old advertisements (the film was edited by Kevin Jones), accompanied by a sensitive score by Steven Emerson/Ever Studio.

Noyes’s career trajectory took a turn at the 1970 International Design Conference Aspen, which he headed, when the theme of design fusing with the environment was seized upon by counterculture activists to protest against corporate greed, the Vietnam War, and the misuse of natural resources by design firms. The conference was filmed by his son Eli and director Claudia Weil, who captured intense moments. “I’m not a political guy. I’m interested in making my points through my work,” the elder Noyes tells Oscar-winning graphic designer Saul Bass. (Eli, who died this past March at the age of eighty-one, had been nominated for an Oscar for his 1964 claymation short Clay or the Origin of Species.)

“The designers who were at Aspen, their consciousness was good design can change things. I think Eliot Noyes would profess this,” Chip Lord, the cofounder of the alternative architecture collective Ant Farm and a conference attendee, explains. “Good design makes a good product or a good branding. It is a form of change. But our critique was beyond that because it didn’t matter how well you designed a gigantic SUV if it’s just guzzling fuel.”

The conference changed Noyes; he resigned from the IDCA and spent more time with his family. His children note that they really didn’t get to know their father until his later years, including a particularly memorable trip together.

Noyes died in 1977 at the age of sixty-six; he may not be a household name, but his impact on the visual and architectural history of twentieth-century American culture is still unmistakable in corporations and households around the world.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]