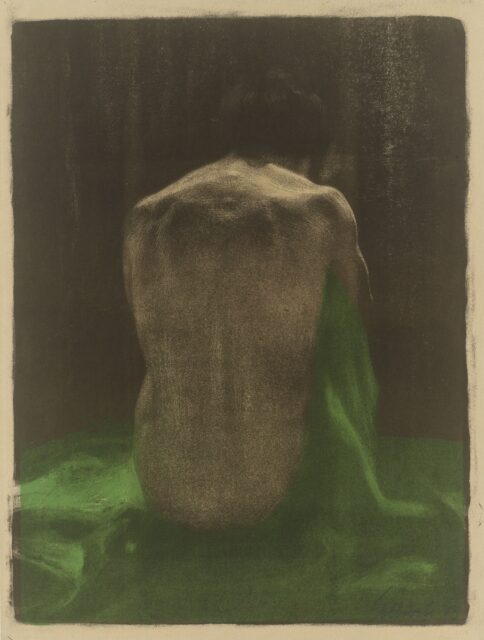

Käthe Kollwitz, Female Nude, from Behind, on Green Cloth (Weiblicher Rückenakt auf grünem Tuch), crayon and brush lithograph with scraping needle, printed in two colors on brown paper, 1903 (Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / © Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / photo by Herbert Boswank)

KÄTHE KOLLWITZ

MoMA, the Edward Steichen Galleries, third floor south

11 West Fifty-Third St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Through July 20, $17-$30

www.moma.org

“My art serves a purpose. I want to exert an influence in my own time, in which human beings are so helpless and destitute,” artist Käthe Kollwitz said. The depiction of the helpless and destitute were central to Kollwitz, who was born in Prussia in 1867, spent almost fifty years based in Berlin, and died in Saxony in 1945, experiencing two world wars and a global depression. Kollwitz’s dark world view is on display in the poignant and powerful MoMA exhibition simply titled “Käthe Kollwitz,” consisting of approximately 120 prints, drawings, and sculptures that envelop museumgoers in a haunting atmosphere.

Käthe Kollwitz, War (Krieg), portfolio of seven woodcuts, 1922 (the Museum of Modern Art, New York / Gift of the Arnhold Family in memory of Sigrid Edwards / photo by twi-ny/mdr)

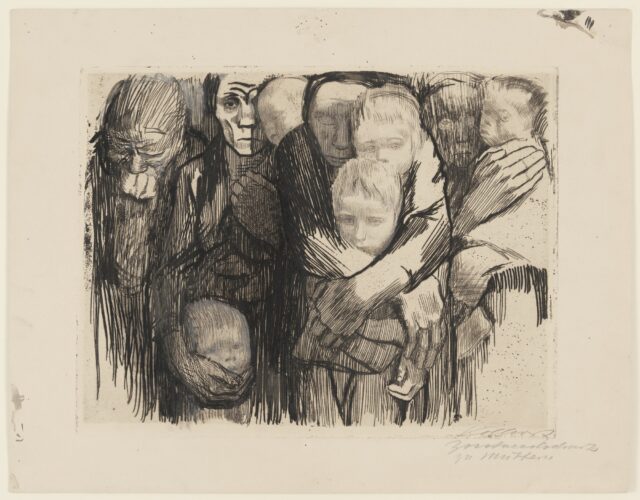

Divided into six sections, “Asserting Herself,” “Forging an Art of Social Purpose,” “Her Creative Process,” “Love and Grief,” “War and Its Aftermath,” and “Maternal Protection,” the show focuses on the struggles of the working class and mothers’ desperate attempts to safeguard their children. Kollwitz was married to a doctor who cared for the poor; they had two sons, one a soldier who was killed during WWI. Using charcoal, black ink, crayon, graphite, and chalk along with etchings, bronzes, woodcuts, and lithographs, she rendered the horrors of the “Peasants’ War,” unemployment, sacrifice, lamentation, and death. The titles alone tell only part of the story: Call of Death, Storming the Gate — Attack, The Downtrodden, Dance around the Guillotine, Death Seizes the Children, and multiple versions of Woman with Dead Child. Even works called Uprising, Charge, Inspiration, Love Scene, The Lovers, and The Survivors are bleak and ghostly.

In the large bronze sculpture Mother with Two Children, a woman clutches her two kids as if in the midst of terrible danger. In The People, skeletal faces are barely visible in the blackness. In Home Worker, Asleep at the Table, a woman has draped her head on a table, overwhelmed with exhaustion, looking as if she never wants to get up again. In Love Scene I, a man and a woman hold tight to each other as if barely clinging to life. In The Mothers, a group of women are huddled in a circle, forming a kind of human shield. And in self-portraits dating from 1890 to 1934, Kollwitz looks directly at the viewer in an almost accusatory manner, demanding we take action; the portraits continue until she is old and forlorn, as if it’s too late.

Käthe Kollwitz, The Mothers (Mütter), line etching, sandpaper, needle bundle, and soft ground with the imprint of laid paper overworked with black ink, opaque white, charcoal, and pencil, 1918 (collection Ute Kahl, Cologne. Fuis Photographie)

“I have no right to withdraw from the responsibility of being an advocate,” Kollwitz wrote. “It is my duty to voice the sufferings of men, the never-ending sufferings heaped mountain-high.”

This stunning exhibition captures all that and more — and, sadly, serves today as a frightening warning.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]