Annie Dorsen pits herself against ChatGPT in Prometheus Firebringer (photo by Maria Baranova)

PROMETHEUS FIREBRINGER

Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center

262 Ashland Pl. between Lafayette Ave. & Fulton St.

Through October 1, $50

866-811-4111

www.tfana.org

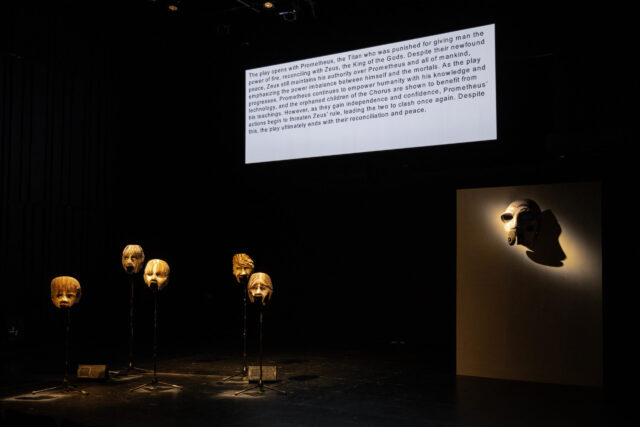

As the audience enters Theatre for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center for Annie Dorsen’s Prometheus Firebringer, text is being projected one letter at a time on a white screen above the stage. Below are five AI-generated mask faces on poles, while a more menacing mask hovers at the top of a wall at the center of the stage, perhaps suggesting the traditional comedy and tragedy masks that decorate so many prosceniums.

The text of the paragraph appears over and over again, each time with significant differences, but they all tell the same story, summarizing the plot of Aeschylus’s unfinished Prometheia trilogy, which began with Prometheus Bound and continued with Prometheus Unbound and Prometheus the Fire-bringer; only eleven fragments of Unbound exist, and only one line of the finale.

The recaps are being generated live by ChatGPT-3.5, scanning the internet and regurgitating the tale of Prometheus’s battle with Zeus in language that repositions key words, plot points, and themes, reminding us how many ways there are to say the same thing.

Writer-director Dorsen enters stage left and sits at a plain wooden desk with paper, a water bottle, and a microphone. When GPT-3.5 is done, she begins a unique kind of lecture. “I am going to try to talk to you about the individual in the contemporary age,” she says. “I suppose this piece is an essay, maybe, a think piece. It doesn’t really matter what it is, I call it an ‘essay’ because it is not anything more.”

A Greek chorus of masks shares the story of Prometheus in TFANA production (photo by Maria Baranova)

From this point on, the lecture-performance alternates between Dorsen’s “essay” and the masks performing parts of Aeschylus’s conclusion to the Prometheus trilogy, in which the five masks — a chorus of orphaned children — sing and the larger mask narrates the tale. The fight between Zeus and Prometheus over power and control mimics that between AI and human writers and philosophers.

As with GPT-3.5, nothing Dorsen is saying is original; every single word and phrase has come from sources she carefully researched. As she speaks, those sources are cited via projections on a screen behind her. The sources range from Bernard Stiegler’s Symbolic Misery Vol. I: The Hyperindustrial Epoch, Ted Berrigan’s On the Level Everyday: Selected Talks on Poetry and the Art of Living, The Twilight Zone, Jakob Norberg’s Tragedy of the Commonplace, Gregg Lambert’s The Elements of Foucault, and Simon Critchley’s Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us to Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, Mark Grabowski and Eric P. Robinson’s Cyber Law and Ethics: Regulation of the Connected, E. A. Havelock’s The Crucifixion of Intellectual Man, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Ted Chiang’s “ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web” in the New Yorker, and Noam Chomsky’s “The False Promise of ChatGPT” in the New York Times.

Whereas GPT-3.5 produces comprehensible strings of words by searching archives and databases for expected patterns, Dorsen works in the opposite direction; she knows what she wants to say and then finds the word strings through her research. She pulls both important phrases and more mundane thoughts and sentences from books and articles that don’t always have anything to do with her topic. For example, when she greets the audience, saying, “Hi. Thanks for coming,” she cites R. H. Wood’s Lightning Crashes. When she notes, “We are together in time,” her source is Christina Baldwin’s Our Turn Our Time: Women Truly Coming of Age. GPT-3.5 seems to act more randomly, while Dorsen is building a coherent argument.

Talking about language, Dorsen explains, “It is a shared resource, it belongs to us all, and words are never consumed, no matter how often we use them. I chose these words carefully. I chose these words carefully, because they resonate with my experiences. But what do I mean by experience? And whose??? Mine or theirs? In other words, who is speaking?”

Artificial intelligence investigates Aeschylus’s unfinished play in Prometheus Firebringer (photo by Maria Baranova)

Dorsen and the play-within-a-play explore tragedy, choices, coding, fate, recombining, and the past. The most effective section is when Dorsen describes how Irish artist Matt Loughrey used AI to colorize black-and-white photos of victims of the Khmer Rouge, but he also gave them all smiles. “If these photos are part of current AI models that’ll represent a total rewrite of history, in an absolutely frightening way,” Dorsen points out. “How can you change hell to happiness?”

Prometheus Firebringer concludes Dorsen’s algorithmic theater trilogy, which began with 2010’s Hello Hi There, followed by last year’s A Piece of Work. As clever as it is, there is also an overwhelming dryness to it. The interplay between the AI and Dorsen never, well, ignites. The excerpts “performed” by the masks, whose eyes are like video screens, are dull and lifeless; Dorsen’s lecture is much more fun and interesting, but there is not enough of it. The entire production, previously seen at the Chocolate Factory in Queens, is extremely slight at a mere forty-five minutes.

Earlier this month I saw Tjaša Ferme’s Bioadapted at CultureLab LIC, which was more successful in dramatizing a narrative involving AI and GPT-3. Of course, Dorsen (The Great Outdoors, Magical) is showing us that human activity is more viable and entertaining than that created by AI, but the proceedings lag too much. Prometheus needs to bring some fire.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]