Robert H. Lieberman’s Echoes of the Empire is a love letter to Mongolia

ECHOES OF THE EMPIRE: BEYOND GENGHIS KHAN (Robert H. Lieberman, 2021)

Streaming on demand

www.echoesoftheempire.com

I recently spent two weeks in Mongolia, traveling across the steppes and the Gobi Desert before finishing our journey in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar, known as UB. I’d never experienced anything like that; for most of our time there, we saw more animals (sheep, goats, horses, cows, gazelles, camels) than people, meeting nomadic herders, staying in gers (Mongolian yurts), and learning about Chinggis Khan, the famous Mongol warrior known to the West as Genghis Khan. His name and image are everywhere: statues and monuments, museums, beer bottles, paintings, the airport.

Shortly after returning to bustling New York City, I watched filmmaker and novelist Robert H. Lieberman’s beautiful documentary Echoes of the Empire: Beyond Genghis Khan, which is now available for online streaming after playing the festival circuit. The film, the conclusion of a trilogy that began with Angkor Awakens and They Call It Myanmar, wonderfully captures the Mongolia I had just toured as it explores the land’s history, from its unique topography and weather (particularly the wind) and Chinggis Khan’s power in the thirteenth century to the Soviet influence beginning in 1921 and the arrival of democracy and a new constitution in 1992. Essentially, Mongolia today is a very young country, barely thirty years old, with a very old culture. There’s a lot to learn as it reclaims its culture — Mongolians were not allowed to even say the name “Chinggis Khan” under the Soviets — and develops much-needed infrastructure as nomads who live as their ancestors have done for more than a thousand years now head to the big city to make a new life.

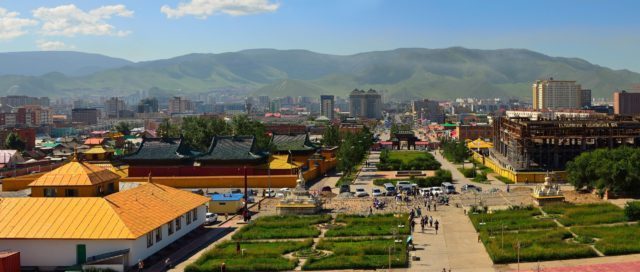

Echoes opens with gorgeous aerial shots by Michael Roberts of animals moving through vast landscapes of grass, sand, and mountains before the camera reveals UB, the past meeting the present and future as lush traditional music plays.

“As a child, I grew up on horseback leading camel caravans on the steppe,” poet G.Mend-Ooyo fondly remembers. “The nomadic life is the closest lifestyle to nature. During the summer, my family left our ger’s door open. Through the door frame, the outside always looked as if it were a painting, changing from dawn to dusk. It was like I was looking at a framed painting. This was my childhood art gallery as I grew up in a nomadic family.” I felt the same thing numerous times during my trip.

Jack Weatherford, author of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, notes, “The people move constantly, and the air moves constantly. When you’re crossing the steppe, you can go for hours and sometimes days without seeing a human habitation, but you always look for the animals, because once you see the animals, you know there are going to be people somewhere close by.” He describes the basic conventions of the ger and how herders live. “You walk into the ger and you smell family; you know that you’re home.”

Rutgers scholar Simon Wickhamsmith points out, “Mongolia today seems to me a very modern society on the surface, but just below the surface there is a feeling of great antiquity and a tremendous respect for the history and the traditional culture.”

Lieberman also speaks with journalist and filmmaker Peter Bittner, former US ambassador to Mongolia Jonathan Addleton, Mongolia Quest director D.Gereltuv, ecologist and conservation biologist T.Batbayar, Cornell biologist Allen MacNeill, economist and teacher S.Unur, University of Delaware ethnomusicologist Sunmin Yoon, and others, giving wide-ranging perspectives of Mongolia, from its land to its politics.

Activist and former Parliament member Oyungerel Tsedevdamba talks about the importance of song in nomadic culture. “That’s the only entertainment they have,” she says. When we were invited into a ger by a herder, he and his friends sang a traditional song for us. (After we had lunch, they also showed us how to tame a wild horse.)

Weatherford shares the details of Chinggis Khan’s early life, from the death of his father, the shunning of his widowed mother, and the abduction of his wife to his growing expertise in battle and his successful invasions, told with animation by Camilo Nascimento. “We remember the conquests, and the conquest was harsh, it was brutal, and it was bloody,” Weatherford states. “But no empire survives on war. War is only one phase. Empire survives when the people prosper in some way from it.” Weatherford discusses the growth of commerce, the spreading of information, religious freedom, women’s rights, diplomatic immunity, and international law that came to be under the Mongol warrior’s leadership.

Echoes of the Empire focuses on both the humans and the animals of Mongolia

As Lieberman turns to the current day, the documentary delves into problems with coal, the untenable population growth surrounding UB with districts that lack running water or paved streets, the constant traffic and pollution, and the need to reinvent the ger now that so many Mongolians are using them as permanent homes.

“Sadly, we live on a tiny part of our vast territory, which led to density and a stressful life,” G.Mend-Ooyo opines. “In fact, living in the wilderness and steppe is nowhere near as stressful as city life, but rather it is freedom.”

Gracefully edited by David Kossack and photographed by Lieberman, who produced the film with Deborah C. Hoard, Echoes of the Empire is a love letter to the extraordinary country of Mongolia, from its past to its present, but it comes with a warning about its immediate future, which was evident during my travels there as well. I highly recommend the film — and a trip to Mongolia, an experience like no other.