Who: Patricia G. Berman, MaryClaire Pappas, Edward Gallagher

What: Live virtual discussion and exhibition tour

Where: Scandinavia House YouTube

When: Saturday, April 2, free, 1:00 (exhibition continues at 58 Park Ave. at 38th St. through June 4)

Why: Norwegian painter and sculptor Edvard Munch “seems to have been one of the first artists in history to take ‘selfies,’” notes the introductory wall text to the Scandinavia House exhibition “The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography.” As the free show — which has been brought back, with some wonderful design changes that provide deeper perspective, for an encore run extended through June 4 — reveals, that statement does not just refer to Munch’s penchant for self-portraiture, as demonstrated in the 2018 Met exhibit “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed,” which included a detailed look at Munch’s depiction of himself over the years. “Munch painted self-portraits throughout his career, but with increased intensity and frequency after 1900,” Gary Garrels, Jon-Ove Steihaug, and Sheena Wagstaff write in the introduction to the Met catalog. “These ‘self-scrutinies,’ as he called them, provide insight into his perceptions of his role as an artist, as a man in society, and as a protagonist in his relationships with others, especially women. . . . Using himself as subject but always allowing technique to influence effect, Munch was able to powerfully investigate the interplay between depicting external reality and meditating on painterly means.”

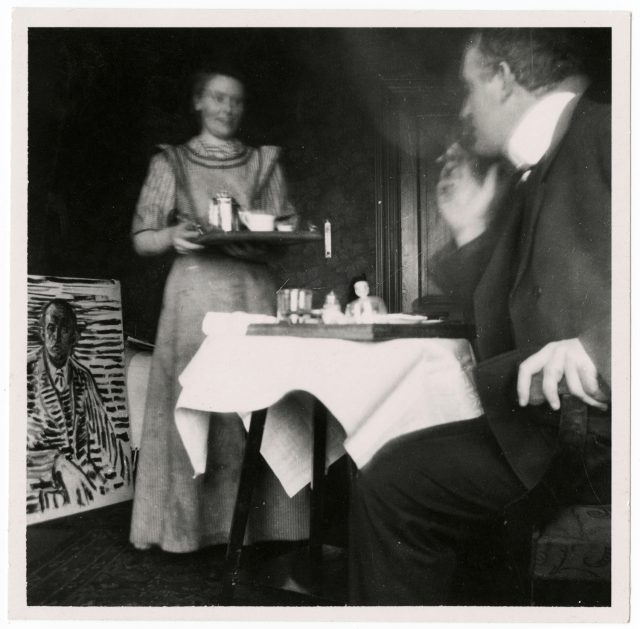

Edvard Munch, “Self-Portrait at the Breakfast Table at Dr. Jacobson’s Clinic,” gelatin silver contact print, 1908-09 (courtesy of Munch Museum)

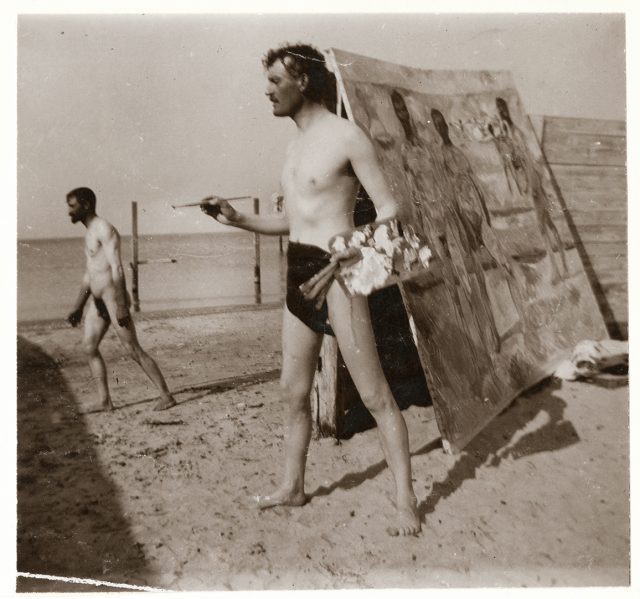

At Scandinavia House, this is evident in his fascination with photography, which he took up during two periods of his life that were fraught with physical and health issues. Munch snapped photographs between 1902 and 1910, after his lover, Tulla Larsen, shot him in the left finger, and again from 1927 to the mid-1930s, suffering a hemorrhage in his right eye in 1930. He also took home movies with a camera in 1927. As in his paintings and particularly his prints, Munch experimented with photographic images, playing with exposure length, camera angles, movement, and shadows for his Fatal Destiny portfolio and individual works. He is purposely blurry in “Self-Portrait in Profile Indoors in Åsgårdstrand,” “Self-Portrait at the Breakfast Table at Dr. Jacobson’s Clinic,” and “Self-Portrait ‘à la Marat,’ Beside a Bathtub at Dr. Jacobson’s Clinic.” He is completely naked, holding a sword in 1903’s “Edvard Munch Posing Nude in Åsgårdstrand,” a kind of companion piece to 1907’s “Self-Portrait on Beach with Brushes and Palette in Warnemünde,” in which he holds a paintbrush. The woman in “Nurse in Black, Jacobson’s Clinic,” from 1908-09, has a lot in common with Munch’s 1891 oil painting, “Lady in Black.” There are multiple, ghostly images of both subjects in 1907’s “Edvard Munch and Rosa Meissner in Warnemünde,” evoking the phantasmic bodies in several prints on view, including “Moonlight II.”

On April 2, American-Scandinavian Foundation president Edward Gallagher will moderate a special live, online presentation with curator Patricia G. Berman giving an up-close look at several photographs in the show, ASF Research Fellow MaryClaire Pappas talking about Munch’s self-portraiture, and a panel discussion on Munch’s relevance to twenty-first-century photography. You can check out the exhibit from home using the new virtual tour here.

Edvard Munch, “Self-Portrait on Beach with Brushes and Palette in Warnemünde,” Collodion contact print, 1907 (courtesy of Munch Museum)

In the Met catalog, in her essay “The Untimely Face of Munch,” Allison Morehead explains, “‘He is not attached to any school or any direction,’ wrote the Norwegian critic and art historian Jappe Nilssen in 1916, ‘because he himself is one of those who advances and creates his own school and forges his own direction.’ Surely with Munch’s complicity, Nilssen described his friend as both stereotypical avant-garde outsider and chronological anomaly, as an art history unto himself, his own school, his own doctrine, and his own teleology. Perhaps then it is little wonder that Munch made so many self-portraits from the beginning to the end of his career, regularly depicting himself in paintings, prints, drawings, and photographs, and also little wonder that art historians have found them so preoccupying.’”

The Scandinavia House show, which has added a case of vintage camera equipment and a short video by Berman and is divided into such sections as “Landscape of Healing,” “Munch’s Selfies,” and “The Amateur Photographer,” concludes with a short compilation of home movies Munch shot with a Pathé-Baby camera, in which the artist once again focuses on himself as his subject. “I have an old camera with which I have taken countless pictures of myself, often with amazing results,” he said in 1930. “Some day when I am old, and I have nothing better to do than write my autobiography, all my self-portraits will see the light of day again.” It’s fascinating to consider just what Munch, who died in 1944 at the age of eighty, would have thought of contemporary social media and the selfie, offering new opportunities to shine a light on himself.