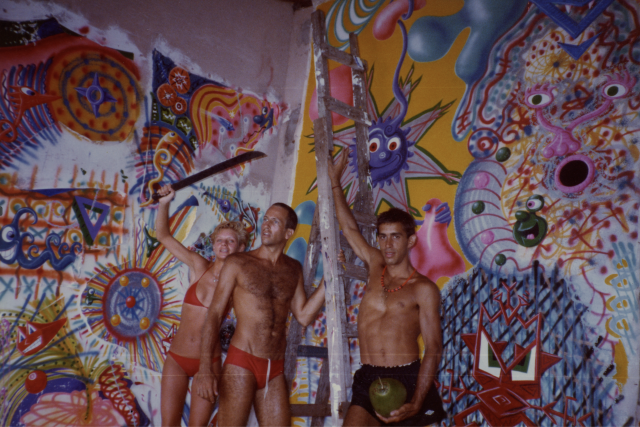

Min Sanchez, Kenny Scharf, and Oliver Sanchez pose in front of Scharf’s artwork in Bahia, Brazil (photo by Tereza Scharf)

KENNY SCHARF: WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE (Malia Scharf & Max Basch, 2020)

Available on demand

www.kennyscharfmovie.com

“I have a balancing act between being a responsible adult and the Peter Pan syndrome because I just feel like life is so much about the moment, so I want every moment fun and beautiful,” Kenny Scharf says in the new documentary Kenny Scharf: When Worlds Collide. “It’s not reality.” Codirectors Max Basch and Malia Scharf — one of the artist’s daughters — try to make every moment of the film, now streaming on demand, fun and beautiful, often reaching that goal.

Shot over a period of eleven years, When Worlds Collide follows Scharf, who was born in 1958 in Los Angeles and moved to Manhattan to attend SVA, from his early days as a graffiti artist and muralist, when he met and became great friends with Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat and hung out with Andy Warhol at the Factory, to his vast popularity creating fantastical, colorful creatures in paintings and sculptures, from the lean years to his current obsession with recycling. “Use everything,” he says, extolling us to ”not waste precious plastic when you can turn it into bathroom sculpture” as he adds a plastic cup and straw to an ever-evolving work above his toilet.

Scharf and Basch, who also served as editor and one of the cinematographers, speak with former Ferus Gallery owner Irving Blum, art collector Peter Brant, gallerists Jeffrey Deitch and Tony Shafrazi, writer and poet Carter Ratcliff, art historian Richard Marshall, Whitney curator Jane Panetta, former Scharf assistant Min Sanchez, author and psychologist Gabor Maté, collectors Andy and Christine Hall, real estate developer Tony Goldman, and curator Dan Cameron, who all offer unique perspectives on Scharf as a person and an artist. “There’s no separation between Kenny and his art,” his friend and fellow artist Kitty Brophy says. There are also old and new interviews with such artists as Bruno Schmidt, Ed Ruscha, Samantha McEwen, Robert Williams, Marilyn Minter, KAWS, Dennis Hopper, and Yoko Ono as well as Scharf’s mother, Rose; wife, Tereza; daughters, Zena and Malia; and grandkids Jet and Lua, who share their thoughts and are seen in home movie footage.

“He just created a family where we felt we were understood and accepted for who we are,” actress and performance artist Ann Magnuson says. “The main way to communicate was to get out on the street, and the message got out there and of course the attention came, and then it started to unravel a bit when the success, the money, the fame, and the uptown world started paying attention to the downtown world. Some of that wonderful, naïve idealism was lost.”

The film doesn’t shy away from the devastation of the AIDS crisis or Scharf’s dry periods, when his style of surreal Pop art was out of favor, but he continues to create and is a fan favorite at international art fairs with his eye-catching work. He gets tearful when talking about Haring, shares his love of nature and cartoons (especially The Flintstones and The Jetsons), collects trash on the beach, remembers the influential Club 57, discusses his breakthrough painting, 1984’s When the Worlds Collide, and describes his penchant for pareidolia, seeing faces everywhere. It’s fascinating to watch him stand in front of a canvas, painting right from his imagination, without preparatory sketches. He comes off as a driven artist and dedicated family man who can be an endearing mensch. “Many people think I’m crazy, and I think that’s okay,” he says with a laugh.