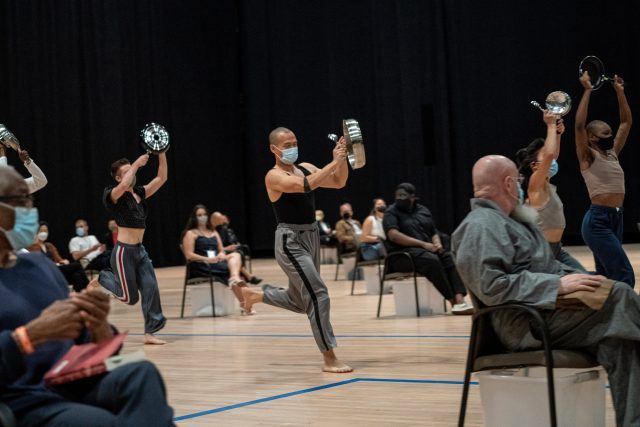

Performers move throughout Park Avenue Armory’s Wade Thompson Drill Hall in Afterwardsness (photo by Stephanie Berger)

AFTERWARDSNESS

Park Ave. Armory

643 Park Ave. at Sixty-Seventh St.

May 19-26, $45

www.armoryonpark.org

Bill T. Jones and Janet Wong have given us the first great indoor, in-person, live dance presentation of and about the pandemic and the social justice movement. Running May 19-26 at Park Avenue Armory, Afterwardsness takes place in the building’s massive fifty-five-thousand-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall, where one hundred audience members are marched in formation to their seats, arranged six feet apart from one another throughout the space. In the center is a large rectangle bordered by yellow tape, evoking caution, while a twisting path in blue (representing police and authority?) is situated on the floor around the chairs, ensuring the performers keep a safe distance from the viewers. (Part of the armory’s Social Distance Hall programming, the production itself was postponed last month when several cast and crew members tested positive for Covid.)

The sixty-five minute show, named for Sigmund Freud’s concept of “a mode of belated understanding or retroactive attribution of sexual or traumatic meaning to earlier events,” is a complex web of physical and emotional pain and fear, performed by eight masked and barefoot dancers wearing sweatpants and T-shirts or tank tops — Barrington Hinds, Chanel Howard, Dean Husted, Shane Larson, s. lumbert, Marie Lloyd Paspe, Nayaa Opong, and Huiwang Zhang — along with Vinson Fraley Jr., who is dressed all in white from head to ankle, as if he were a kind of spiritual leader or ghostly apparition; all are members of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company. They run, roll, jump, walk, tumble, squirm, wriggle, grasp their hands behind their backs, and raise their arms above their heads like they’re under arrest, never touching each other nor making eye contact with the audience. There’s so much happening at any one moment that it’s impossible to take it all in, as if you’re at a protest rally, not knowing where to look.

Bill T. Jones and Janet Wong’s Afterwardsnesstakes an emotional, powerful look at the last fourteen months in America (photo by Stephanie Berger)

The soundtrack is dazzling, featuring avant-garde jazz, snippets of familiar tunes (for example, “Dixie” and “Yankee Doodle,” which both deal with class and race issues), abstract sounds, brief quotes from Jones and members of the company that can’t always be understood, excerpts from Olivier Messaien’s 1941 chamber piece Quartet for the End of Time, written while he was a POW in a German prison, and occasional grunts and noises (and a nursery rhyme). Standing alone in the yellow rectangle, music director Pauline Kim Harris plays the gorgeous, elegiac 8:46 violin solo “Homage,” a tribute to George Floyd; clarinetist Paul Wonjin Cho and others perform from wooden lifeguard chairs; composer Holland Andrews contributes a new song and vocals, including stating the date, beginning with March 13 and continuing through May 19, in one corner with Cho, pianist Vicky Chow, and cellist Caleb van der Swaagh; and the score includes original compositions from Fraley Jr. and Howard, repeating powerful phrases about suppression and murder that echo through the hall. The immersive sound design is by Mark Grey.

Brian H. Scott’s lighting design is a marvel, shifting from bright and airy to dark and ominous. At times he lights only the straight and curved pathways followed by the dancers, tracing the blue lines. He uses spotlights to elicit giant shadows and creates small boxes that trap the dancers, capturing Jones’s strong choreographic language, which ranges from confinement and isolation to freedom and hope. In the grand finale, the performers grab chairs but are hesitant to merely sit in them and watch; their jittery energy makes the audience uncomfortable but fascinated. Afterwardsness is not a dire, depressing fugue for these past fourteen months; it is both a compelling reminder of what has unfolded across America as well as a beautiful yet urgent call to action.