Film fans can watch obsessive film fanatics in Cinemania, streaming at BAM festival

BAM online

December 4 – January 3, free – $12

www.bam.org

Among the endless negative aspects of the pandemic lockdown is our inability to see and interact with our fellow New Yorkers in locations that are special to this great city. We are trapped inside, most of us making only virtual contact with friends, families, work colleagues, and strangers on the street. BAM takes us on a trip down memory lane in the first online edition of its continuing Programmers’ Notebook series, this one titled “New York Lives”; of course, we can’t even go to BAM to watch them in an audience filled with other film fans. In addition to the below recommendations, BAM will be showing Angela Christlieb and Stephen Kijak’s 2002 Cinemania, which follows, well, five obsessed film fans who do whatever they can to see as many movies as possible, each with unusual quirks (and all of whom I used to see at various screenings); Diego Echeverria’s 1984 Los Sures, about Puerto Rican street culture; Loira Limbal’s 2020 Through the Night, a portrait of three caregivers of children; Brett Story’s 2020 The Hottest August, a poetic and poignant look at what New Yorkers think about the future in August 2017; Megan Rossman’s 2019 The Archivettes, which goes inside the Lesbian Herstory Archives; and a double feature of Marci Reaven and Beni Matías’s 1979 The Heart of Loisaida and William Sarokin and Matías’s 1985 Housing Court, both of which explore the housing crisis.

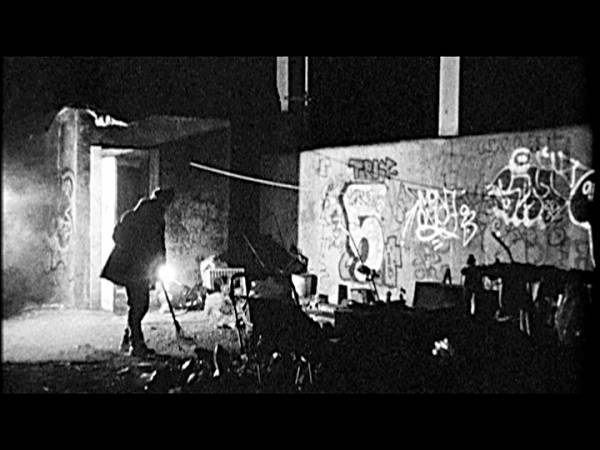

DARK DAYS (Marc Singer, 2000)

Opens December 4, $4.99

www.bam.org

The award-winning documentary Dark Days takes a frightening look at a community of homeless men and women — many of them former or current crack users — who live in the Amtrak tunnels beneath Penn Station. They sleep in tents, cardboard shacks, and small plywood shanties, some of which have been painted and decorated. As the belowground residents shave, cook, play with their pets, and take showers under leaking pipes, trains speed by, and rats scavenge through the countless mounds of garbage. At times some of the men venture aboveground (“up top”) to go through trash cans, mostly looking for recyclable bottles and junk items they can resell. First-time filmmaker Marc Singer became a part of this colony for two years (he initially went down to help the people, not to film them), getting the residents to open up and tell their fascinating stories, which turn out to be filled with a surprising zest for living. In fact, all of the underground shooting was completed with the help of the subjects themselves acting as the crew when they were not on camera. DJ Shadow composed the haunting music for this strangely enriching look at a mysterious, truly terrifying part of New York City.

Crystal Kayiza’s See You Next Time is set in a nail salon that does extraordinary work (photo courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Leroy Farrell)

SEE YOU NEXT TIME: NEIGHBORHOOD STORIES

Wednesday, December 9, free with RSVP, 7:30

www.bam.org

“See You Next Time: Neighborhood Stories” takes viewers on six slice-of-life journeys into unique parts of New York City, local tales about people making a difference or just struggling to get by — while also reminding us of things we cannot do or that have been severely limited during the Covid-19 crisis. In Aisha Amin’s Friday, a Brooklyn community is excited about the potential of acquiring a building to house their mosque. Crystal Kayiza’s See You Next Time introduces us to the relationship between a woman who gets extravagant nails and her salon artist. In Emily Packer and Lesley Steele’s By Way of Canarsie, a coastal community fights for ferry access. In Heather María Ács’s fictional Flourish, drag queen Crystal Visions (Justin Sams) prepares for an important show while battling with her drunk partner, Beau (Becca Blackwell), and young nonbinary couple Lazer (Poppy Liu) and T-Bone (Delfina Cano) consider making an addition to their love life. In Anna Pollack’s fictional Briarpatch, teenage siblings Marcus (Juan Lara) and Ashley (Oumou Traoré) face multiple hardships after the death of their mother. And in Tayler Montague’s semiautobiographical In Sudden Darkness, thirteen-year-old Tati (Sienna Rivers) navigates her way around a blackout. The free screening on December 9 at 7:30 will be followed by a live Q&A with the filmmakers, moderated by programmer Natalie Erazo (RSVP required here).

Manfred Kirchheimer’s Free Time is a symphonic film about a very different time in the city

FREE TIME (Manfred Kirchheimer, 2019)

Opens December 11, $12

www.bam.org

grasshopperfilm.com

In 2019, eighty-eight-year-old Manfred Kirchheimer was at Lincoln Center’s Francesca Beale Theater to screen and discuss his latest work, the subtly dazzling Free Time, which had its world premiere in the Spotlight on Documentary section of the fifty-seventh annual New York Film Festival. The German-born, New York-raised Kirchheimer has taken 16mm black-and-white footage he and Walter Hess shot between 1958 and 1960 in such neighborhoods as Hell’s Kitchen, Washington Heights, Inwood, Queens, and the Upper East Side and turned it into an exquisite city symphony reminiscent of Helen Levitt, Janice Loeb, and James Agee’s classic 1948 short In the Street, which sought to “capture . . . an image of human existence.” Kirchheimer does just that, following a day in the life of New York as kids play stickball, a group of older people set up folding chairs on the sidewalk and read newspapers and gossip, a worker disposes of piles of flattened boxes, laundry hangs from clotheslines between buildings, a woman cleans the outside of her windows while sitting on the ledge, a fire rages at a construction site, and a homeless man pushes his overstuffed cart.

Kirchheimer and Hess focus on shadows under the el train tracks, gargoyles on building facades, smoke emerging from sewer grates, old cars stacked at a junkyard, and grave markers at a cemetery as jazz and classical music is played by Count Basie (“On the Sunny Side of the Street,” “Sandman”), John Lewis (“The Festivals,” “Sammy”), Bach (“The Well Tempered Klavier, Book 1 — Fugue in B flat minor”), Ravel (Sonata for Violin & Cello), and others, with occasional snatches of street sounds. The title of the film is an acknowledgment of a different era, when people actually had free time, now a historical concept with constant electronic contact through social media and the internet and the desperate need for instant gratification. Kirchheimer, whose Dream of a City was shown at the 2018 NYFF and whose poetic Stations of the Elevated was part of the 1981 fest (but not released theatrically until 2014), directed and edited Free Time and did the sound, and it’s a leisurely paced audiovisual marvel. The only unfortunate thing is that it is only an hour long; I could have watched it for days.

Okwui Okpokwasili takes viewers behind the scenes of her one-woman show in Bronx Gothic (photo courtesy of Grasshopper Film)

BRONX GOTHIC (Andrew Rossi, 2017)

Opens December 18, $4.99

www.bam.org

grasshopperfilm.com

“Okwui’s job is to scare people, just to scare them to get them to kind of wake up,” dancer, choreographer, and conceptualist Ralph Lemon says of his frequent collaborator and protégée Okwui Okpokwasili in the powerful documentary Bronx Gothic. Directed by Okpokwasili’s longtime friend Andrew Rossi, the film follows Okpokwasili during the last three months of her tour for her semiautobiographical one-woman show, Bronx Gothic, a fierce, confrontational, yet heart-wrenching production that hits audiences right in the gut. Rossi cuts between scenes from the show — he attached an extra microphone to Okpokwasili’s body to create a stronger, more immediate effect on film — to Parkchester native Okpokwasili giving backstage insight, visiting her Nigerian-born, Bronx-based parents, and spending time with her husband, Peter Born, who directed and designed the show, and their young daughter, Umechi. The performance itself begins with Okpokwasili already moving at the rear of the stage, shaking and vibrating relentlessly, facing away from people as they filter in and take their seats.

She continues those unnerving movements for nearly a half hour (onstage but not in the film) before finally turning around and approaching a mic stand, where she portrays a pair of eleven-year-old girls exchanging deeply personal notes, talking about dreams, sexuality, violence, and abuse as they seek their own identity. “Bronx Gothic is about two girls sharing secrets. . . . It is about the adolescent body going into a new body, inhabiting the body of a brown girl in a world that privileges whiteness,” Okpokwasili, whose other works include Poor People’s TV Room and the Bessie-winning Pent-Up: A Revenge Dance, explains in the film. National Medal of Arts recipient Lemon adds, “It’s about racism, gender politics — it’s not just about these two little black girls in the Bronx.” Rossi includes clips of Okpokwasili performing at MoMA in Lemon’s “On Line” in 2011, developing Bronx Gothic at residencies at Baryshnikov Arts Center and New York Live Arts, and participating in talkbacks at Alverno College in Milwaukee and the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance, where the tour concluded, right next to her childhood church, which brings memories surging back to her.

Okwui Okpokwasili nuzzles her daughter, Umechi, in poignant and timely documentary (photo courtesy of Grasshopper Film)

Rossi is keenly aware of the potentially controversial territory he has entered. “As a white man, I was conscious of the complexity and implications of embarking on a project that revolves around the experience of African American females,” he points out in his director’s statement. “But fundamentally, I believe in an artist’s creative ability to explore topics that are foreign to the artist’s own background. I think this takes on even more resonance when the work itself has an explicit objective to ‘grow our empathic capacity,’ as Okwui says of Bronx Gothic, [seeking] an audience that is composed of ‘black women, black men, Asian women, Asian men, white women, white men, Latina women, Latina men. . . .’” Cinematographers Bryan Sarkinen and Rossi (Page One: Inside the New York Times, The First Monday in May) can’t get enough of Okpokwasili’s mesmerizing face, which commands attention, whether she’s smiling, singing, or crying, as well as her body, which is drenched with sweat in the show. “We have been acculturated to watching brown bodies in pain. I’m asking you to see the brown body. I’m going to be falling, hitting a hardwood floor, and hopefully there is a flood of feeling for a brown body in pain,” Okpokwasili says. Meanwhile, shots of the audience reveal some individuals aghast, some hypnotized, and others looking away.

Editor Andrew Coffman and coeditors Thomas Rivera Montes and Rossi shift from Okpokwasili performing to just being herself, but the film has occasional bumpy transitions; also, Okpokwasili, who wrote the show when she was pregnant, does the vast majority of the talking, echoing her one-woman show but also at times bordering on becoming self-indulgent. (Okpokwasili produced the film with Rossi, while Born serves as one of the executive producers.) But the documentary is a fine introduction to this unique and fearless creative force and a fascinating examination of the development of a timely, brave work.